In China paper was used for intimate cleaning as early as the second century B.C., but there was no toilet paper in classical Europe. In my many, many visits to ancient Roman toilets over the years, I had always heard that Romans used a sponge on a stick to wipe after defecating. In public latrines, the sponge-stick, or tersorium, would then be rinsed in running water and left in a bucket of vinegar for the next poor bastard to use.

In China paper was used for intimate cleaning as early as the second century B.C., but there was no toilet paper in classical Europe. In my many, many visits to ancient Roman toilets over the years, I had always heard that Romans used a sponge on a stick to wipe after defecating. In public latrines, the sponge-stick, or tersorium, would then be rinsed in running water and left in a bucket of vinegar for the next poor bastard to use.

The existence and use of the tersorium is confirmed in ancient writings. Seneca describes the implement in a deeply disturbing anecdote in the 70th of his Letters to Lucilius used to illustrate how people prefer even the worst death if they can choose it themselves over an easier death chosen for them by a master.

Nay, men of the meanest lot in life have by a mighty impulse escaped to safety, and when they were not allowed to die at their own convenience, or to suit themselves in their choice of the instruments of death, they have snatched up whatever was lying ready to hand, and by sheer strength have turned objects which were by nature harmless into weapons of their own. For example, there was lately in a training-school for wild-beast gladiators a German, who was making ready for the morning exhibition; he withdrew in order to relieve himself, – the only thing which he was allowed to do in secret and without the presence of a guard. While so engaged, he seized the stick of wood, tipped with a sponge, which was devoted to the vilest uses, and stuffed it, just as it was, down his throat; thus he blocked up his windpipe, and choked the breath from his body. That was truly to insult death!

As uncomfortable as a communal vinegar-soaked sponge-stick may seem to our delicate modern hygienic sensibilities, at least sponges are soft and vinegar does disinfect. Compared to using a rounded fragment of pottery to wipe yourself with, a tersorium sounds like paradise. Yet, a study co-authored by forensic anthropologist Philippe Charlier (who also co-authored the comparison of Louis XVI’s blood with Henry IV’s head)

published in the British Medical Journal has confirmed that pessoi, ceramic discs thought to be game pieces in ancient chess-like strategy games, were put to a more utilitarian use: scraping away fecal matter after defecation.

Researchers examined two terracotta pessoi, probably fragments from broken amphorae, found in the filling underneath Roman latrines close to excrement deposits. The fragments were recut to have smoother edges, thank God for small favors, and date to the 2nd century A.D. The smaller piece (on the left in the picture) was found on the island of Ustica, just north of Palermo, Sicily, and is 4.7 centimers (1.85 inches) in diameter, 1.7 centimeters (.67 inches) thick. The larger one was found

Researchers examined two terracotta pessoi, probably fragments from broken amphorae, found in the filling underneath Roman latrines close to excrement deposits. The fragments were recut to have smoother edges, thank God for small favors, and date to the 2nd century A.D. The smaller piece (on the left in the picture) was found on the island of Ustica, just north of Palermo, Sicily, and is 4.7 centimers (1.85 inches) in diameter, 1.7 centimeters (.67 inches) thick. The larger one was found  on Gortyn, on the southern coast of Crete, and is 6 centimeters (2.36 inches) in diameter, 1.3 centimeters (0.51 inches) thick. That doesn’t leave much room for clean holding, but I suppose they have to be small enough to be wielded in, uh, tight quarters.

on Gortyn, on the southern coast of Crete, and is 6 centimeters (2.36 inches) in diameter, 1.3 centimeters (0.51 inches) thick. That doesn’t leave much room for clean holding, but I suppose they have to be small enough to be wielded in, uh, tight quarters.

One side of the pessoi were cleaned as part of standard archaeological practice. The other side and the edges were not. Examination of the non-cleaned areas under a microscope found solidified and partially mineralised feces.

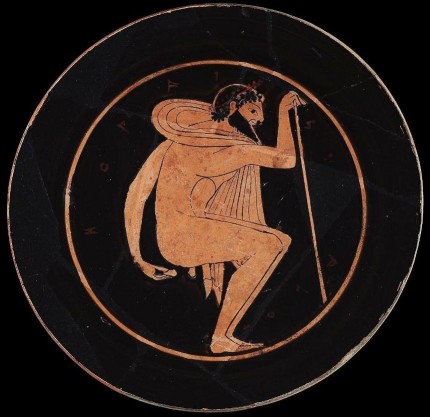

Although this is news to me, many pessoi have been found nestled the excrement deposits under ancient latrines all over the Mediterranean. There is also artistic evidence of the use of pottery fragments for wiping. The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston has a kylix, a wine cup, no less, that has this extraordinary image on the tondo, the flat round inside the cup:

I’m not the only one to whom this story comes as a surprise. Even experts like archaeologists and museum curators are just finding this out now. Dr. Rob Symmons, the curator of the Fishbourne Roman Palace, the largest Roman home in Britain, was highly amused to find all those discs they’ve been exhibiting as game pieces may turn out to have had a less cerebral and more scatological purpose

“The pieces had always been catalogued as broken gaming pieces but I was never particularly happy with that explanation. But when the article produced the theory they were used to wipe people’s bums I thought it was hilarious and it just appealed to me. I love the idea we’ve had these in the museum for 50 years being largely ignored and now they are suddenly engaging items you can relate to.”

Symmons, who has been at the museum for seven years, added: “We will obviously have to think about reclassifying these objects on our catalogue. But we hope the pieces will make people smile when they learn what they were used for.”

He concludes with classic British understatement: “They would have probably been quite scratchy to use and I doubt they would be as comfortable as using toilet roll.”

EDIT: Commenter rwmg rightly notes that the Christmas issue of the BMJ is famous for its spoof and light-hearted articles. This article is most certainly one of the latter, but I can’t say for sure either way if the study itself (ie, the microscopic examination of pessoi) is fictional or if it actually happened but is entertaining enough to include in the Christmas issue. The documentary and archaeological evidence it cites — ancient literary sources, the BMFA kylix, a 2002 article in the journal Hesperia on the pessoi unearthed in the Athenian agora — is factual. You can read the 2002 paper, A contextual approach to pessoi (gaming pieces, counters or convenient wipes?) by John K. Papadopoulos, on pages 423 – 427 of this pdf, and you should because the quotes from Aristophanes alone are worth the price of admission.