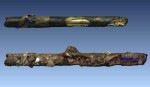

Researchers at the Hunley Project have found an important piece of evidence that has changed what we know about the mysterious demise of the Confederate submarine H. L. Hunley: the exploded remains of the copper torpedo casing still bolted to the spar, the 16-foot-long iron pole that served as the sub’s weapon delivery system.

Researchers at the Hunley Project have found an important piece of evidence that has changed what we know about the mysterious demise of the Confederate submarine H. L. Hunley: the exploded remains of the copper torpedo casing still bolted to the spar, the 16-foot-long iron pole that served as the sub’s weapon delivery system.

The spar has been on display at Clemson University’s Warren Lasch Conservation Lab where the Hunley has been conserved since it was raised from Charleston Harbor in 2000, but since the sub itself was the main priority, conservator Paul Mardikian wasn’t able to begin working on removing the concretions from the spar until last fall. Once the thick concrete-layer of silt and sand was gone, he found that the dense area they had seen on an X-ray was not a release mechanism bur rather the copper sleeve of the torpedo itself. This means the torpedo exploded at the end of the spar, a discovery of critical importance.

The Hunley was the first submarine to successfully sink an enemy ship in wartime. On the night of February 17th, 1864, the 40-foot hand-powered sub manned by a crew of eight rammed its spar torpedo into the starboard stern of the USS Housatonic, a 205-foot, 1,260-ton Union warship that was part of the fleet blockading Charleston Harbor. The blast blew a hole in the ship so wide that witnesses report seeing a couch float out of the hole sideways. Within minutes the Housatonic was sunk and five sailors dead (most survived on row boats and the others climbed the sail rigging that remained above the harbor’s water level).

The Hunley was the first submarine to successfully sink an enemy ship in wartime. On the night of February 17th, 1864, the 40-foot hand-powered sub manned by a crew of eight rammed its spar torpedo into the starboard stern of the USS Housatonic, a 205-foot, 1,260-ton Union warship that was part of the fleet blockading Charleston Harbor. The blast blew a hole in the ship so wide that witnesses report seeing a couch float out of the hole sideways. Within minutes the Housatonic was sunk and five sailors dead (most survived on row boats and the others climbed the sail rigging that remained above the harbor’s water level).

We know the Hunley survived the explosion because the commander of Fort Moultrie on Sullivan’s Island saw the submarine signal with a blue magnesium light indicating the success of the mission. Other witnesses, including one on the Housatonic, also reported seeing the blue signal light. After that, the Hunley and its crew was never heard from again. It sank just outside Charleston Harbor where it remained, buried in sand and silt, until it was raised in 2000.

What the torpedo casing on the tip of the spar proves is that the Hunley was much closer to the Housatonic at the time of the explosion than anyone realized.

What the torpedo casing on the tip of the spar proves is that the Hunley was much closer to the Housatonic at the time of the explosion than anyone realized.

Until now, the conventional wisdom has been the Hunley would ram the spar torpedo into her target and then back away, causing the torpedo to slip off the spar. A rope from the torpedo to the submarine would spool out and detonate once the submarine was at a safe distance. This theory has always had difficulty under scrutiny since it would be very hard to actually lodge the torpedo into the hull of the enemy ship.

Finding a portion of the original torpedo casing has enabled the team to confirm a long held suspicion that it was built and designed by a group associated with Edgar Singer (cousin of the famous sewing machine entrepreneur Isaac Singer). A period diagram housed at the National Archives indicates that this Singer torpedo held 135 pounds of gunpowder and was detonated by a trigger mechanism.

This means the Captain had to position the torpedo while still attached to the spar and trigger it when the time was right.

Since the spar is just over 16 feet long and the torpedo was two feet long, the Hunley was less than 20 feet from the warship when those 135 pounds of black powder blew. At that distance, the crew could have been stunned by a shock wave. Even if only a few of the eight crewmen were knocked unconscious, the hand-cranked propulsion system that kept the vessel moving would have been severely undermined.

This possibility is supported by a clue straight out of Agatha Christie: Lieutenant George E. Dixon’s pocket watch was found stopped at 8:23 PM, almost exactly the time the Housatonic crew reported being under attack. Also, the remains of all eight men were found at their stations. There is no evidence that they tried to escape.

This possibility is supported by a clue straight out of Agatha Christie: Lieutenant George E. Dixon’s pocket watch was found stopped at 8:23 PM, almost exactly the time the Housatonic crew reported being under attack. Also, the remains of all eight men were found at their stations. There is no evidence that they tried to escape.

The new information about the spar torpedo gives researchers precious information that will allow them to run computer models and simulations of how the explosion affected the Hunley. They now have physical evidence — so much of the eye-witness evidence and conventional wisdom has turned out to be completely wrong — of the distance between submarine and ship, and of the strength of the payload. Hunley Project researchers hope to enlist the aid of third party computer modeling experts to simulate the blast, and then perhaps to create scale models of the attack.

Since thick concretions coat the body of the submarine, we still don’t know if it was disabled in any way by the explosion. Conservation has been everyone’s top priority since 137 years in salt water is not kind to iron. The vessel, submerged in a 90,000-gallon tank of cold fresh water at the Warren Lasch Conservation Center, was turned upright in June of 2011 after spending more than 10 years on its starboard side in a truss. The truss only came off two weeks ago, revealing the submarine surface in its unobstructed entirety.

Since thick concretions coat the body of the submarine, we still don’t know if it was disabled in any way by the explosion. Conservation has been everyone’s top priority since 137 years in salt water is not kind to iron. The vessel, submerged in a 90,000-gallon tank of cold fresh water at the Warren Lasch Conservation Center, was turned upright in June of 2011 after spending more than 10 years on its starboard side in a truss. The truss only came off two weeks ago, revealing the submarine surface in its unobstructed entirety.

At the end of this year, WLCC scientists hope to replace the fresh water in the tank with a chemical bath that will slowly leach the salt out of the iron. Once the solution has had a few months to do its thing, researchers plan to remove the encrusted layer of silt, sand and rock. This will allow the chemicals direct access to the iron which will speed up the salt removal and will allow examination of the iron skin. Scientists hope this will answer many of the remaining questions about how and whether the sub was damaged in the attack.