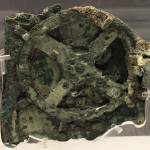

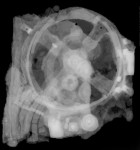

The Roman shipwreck off the coast of the Greek island of Antikythera, famous as the source of the bronze gear device of incredible complexity known as the Antikythera mechanism, hasn’t been surveyed since Jacques Costeau led an expedition to the wreck in 1976. The wreck was first discovered in 1900 by sponge divers using those old timey diving suits with metal helmets which allowed them to go 200 feet down to the steep Aegean slope where artifacts from a first century B.C. wreck were piled on the floor. Over the next two years, divers recovered bronze and marble sculptures and one thickly encrusted bronze artifact of nebulous use that would take decades to be recognized as an astronomical calculator and the world’s oldest surviving analog computer.

The Roman shipwreck off the coast of the Greek island of Antikythera, famous as the source of the bronze gear device of incredible complexity known as the Antikythera mechanism, hasn’t been surveyed since Jacques Costeau led an expedition to the wreck in 1976. The wreck was first discovered in 1900 by sponge divers using those old timey diving suits with metal helmets which allowed them to go 200 feet down to the steep Aegean slope where artifacts from a first century B.C. wreck were piled on the floor. Over the next two years, divers recovered bronze and marble sculptures and one thickly encrusted bronze artifact of nebulous use that would take decades to be recognized as an astronomical calculator and the world’s oldest surviving analog computer.

Although the wreck was thoroughly mined for archaeological gold, the turn of the century divers didn’t have the technology to properly survey the site. This made dating the wreck difficult since the artifacts dated from different eras of Greek history. They wreck itself was Roman, a ship crammed full of loot from Greece in the wake of a military victory, probably. The pottery types suggested dates ranging between 80 and 50 B.C. Cousteau’s team found a coin that dates between 76 and 67 B.C.

Although the wreck was thoroughly mined for archaeological gold, the turn of the century divers didn’t have the technology to properly survey the site. This made dating the wreck difficult since the artifacts dated from different eras of Greek history. They wreck itself was Roman, a ship crammed full of loot from Greece in the wake of a military victory, probably. The pottery types suggested dates ranging between 80 and 50 B.C. Cousteau’s team found a coin that dates between 76 and 67 B.C.

The challenges of diving to the wreck spot have kept people from returning to perform a modern survey. In October of 2012, archaeologist Brendan P. Foley of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution a small team of experts with specialized technology that allowed for extended dives as deep as 230 feet returned to Antikythera. They studied the Cousteau expedition logs and film as a starting point, because the artifacts have pretty much been picked clean, so they needed to identify by matching the underwater geology.

Information is limited, however. Cousteau was only there two days and his team could only spend a few minutes at a time diving to keep from getting the bends. Also, Cousteau staged some of the shoots for drama purposes, they can’t be sure they’re exploring the same wreck site he explored. The debris field could be part of the original wreck. It could have shifted over the millennia — the sponge divers told tales of colossal statues rolling down the slope to depths where they could not follow — or it could be another ship that went down in the deep shoals off Antikythera.

In October, diving with technical scuba gear and diver propulsion vehicles that look like underwater fans, the team found the sweet spot, marked by a scattering of amphora, or large curved jars.

Intact artifacts from the wreck were spread over a huge area, about 197 feet (60 meters) long at depths ranging from 114 feet to 197 feet (35 to 60 m), Foley said. That’s large for an ancient shipwreck, Foley said, suggesting either a huge ship or perhaps more than one wreck. The findings are preliminary, Foley said, but the team may have ultimately been excavating 984 feet (300 m) away from the site explored by Cousteau. If that’s the case, he said, they may have found a separate wreck — likely part of the same fleet as the original wreck that went down in the same storm.

A massive debris field that hasn’t been interfered with is an archaeological gold mine. One amphora has been recovered. It will be DNA tested so the contents can be identified. Dozens of heavily concreted artifacts litter the sea floor, which is what the Antikythera mechanism looked just like that when it was first discovered. There could be any metallic fragment underneath all that calcification so let’s not get too hopped up, but the Romans had good taste in pillage so it’s hard not to be excited at what might be.

A lead anchor was also discovered on top of other artifacts indicating it was stowed on the deck when the ship went down. The position of the artifacts suggest the ship sank suddenly when a storm crashed it against an underwater cliff. According to marine archaeologist Theotokis Theodoulou of Greece’s Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities, the wreck “settled facing backwards with its stern at the deepest point.” The stern was so deep that the sponge divers were never able to reach it.

A lead anchor was also discovered on top of other artifacts indicating it was stowed on the deck when the ship went down. The position of the artifacts suggest the ship sank suddenly when a storm crashed it against an underwater cliff. According to marine archaeologist Theotokis Theodoulou of Greece’s Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities, the wreck “settled facing backwards with its stern at the deepest point.” The stern was so deep that the sponge divers were never able to reach it.

This survey was a preliminary three-week expedition which will be followed up with more extensive surveys over the next two years. Divers will bring metal detectors with them when they return which will allow them to look for artifacts that are not visible under the sand.