Bonham’s is selling a portrait of an 18th century bare-knuckle boxer named George Stevenson. Although the artist is unknown and it looks a lot like half of a 1760s painting by John Hamilton Mortimer (see below), the pre-sale estimate is $16,000 – $24,000, because it’s rare to find 18th century paintings depicting boxing and because George Stevenson played an important role in the history of the sport, although sadly not through his victories. It was his death in the ring in 1741 at the ends of champion Jack Broughton that changed boxing forever, inspiring the first rules that would transform the free-for-all practices of fisticuffs into a more structured sport with clear boundaries of fair play.

Bonham’s is selling a portrait of an 18th century bare-knuckle boxer named George Stevenson. Although the artist is unknown and it looks a lot like half of a 1760s painting by John Hamilton Mortimer (see below), the pre-sale estimate is $16,000 – $24,000, because it’s rare to find 18th century paintings depicting boxing and because George Stevenson played an important role in the history of the sport, although sadly not through his victories. It was his death in the ring in 1741 at the ends of champion Jack Broughton that changed boxing forever, inspiring the first rules that would transform the free-for-all practices of fisticuffs into a more structured sport with clear boundaries of fair play.

Although fist-fighting as a sport was popular in the ancient world from Sumer to Ancient Greece, after the fall of Rome bare knuckles gave way to weapons in the martial arts. There were still forms of spectator fist-fighting to be found, particularly in Italy and Russia, but it was in England where boxing was revived in the 16th century. The first recorded modern prizefight happened in January, 1681. We don’t know the fighters’ names, just their employer because it was a very Upstairs-Downstairs sort of thing. Here is the description of the event written up in The London Protestant Mercury:

“Yesterday a match of boxing was performed before his Grace, the Duke of Albemarle, between the Duke’s footman and a butcher. The latter won the prize, as he hath done many others before, being account, though but a small man, the best at that exercise in England.”

Aristocratic patronage would remain a constant as the sport rose to prominence although thankfully not in the direct service relationship of the Duke’s footman and butcher. The first heavyweight boxing champion, backed by the Earl of Peterborough, would make a name for himself 20 years after that first recorded bout. James Figg was an accomplished martial artist who was as adept with the sword and cudgel as he was with his bare fists. He reigned as undefeated champion from 1719 to 1730 (at least; records from this time are sparse and less than reliable) and started a school where he taught boxing, fencing with the small backsword and quarterstaff fighting.

Aristocratic patronage would remain a constant as the sport rose to prominence although thankfully not in the direct service relationship of the Duke’s footman and butcher. The first heavyweight boxing champion, backed by the Earl of Peterborough, would make a name for himself 20 years after that first recorded bout. James Figg was an accomplished martial artist who was as adept with the sword and cudgel as he was with his bare fists. He reigned as undefeated champion from 1719 to 1730 (at least; records from this time are sparse and less than reliable) and started a school where he taught boxing, fencing with the small backsword and quarterstaff fighting.

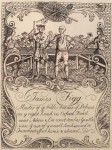

He also built an amphitheater for prizefights which helped popularize the sport. It had the first raised platform ring. Aristocrats and famous people took classes at Figg’s school and flocked to his arena to watch the fights. Satirist printmaker William Hogarth was a great friend and fan. He designed Figg’s business card, painted a portrait of Figg staring boldly at the viewer with his fists clenched in front of him and included images of Figg in several of his famous prints, although he’s holding swords and staffs in those rather than posed for boxing.

He also built an amphitheater for prizefights which helped popularize the sport. It had the first raised platform ring. Aristocrats and famous people took classes at Figg’s school and flocked to his arena to watch the fights. Satirist printmaker William Hogarth was a great friend and fan. He designed Figg’s business card, painted a portrait of Figg staring boldly at the viewer with his fists clenched in front of him and included images of Figg in several of his famous prints, although he’s holding swords and staffs in those rather than posed for boxing.

One of Figg’s students was Jack Broughton, a waterman whose well-muscled physique was first built rowing paying passengers across the Thames. Broughton beat all comers and claimed the title of Champion of England at the Heavyweight from 1738, when he defeated Figg’s successor George Taylor, to 1750. One of those comers was George “The Coachman” Stevenson, who went up against Broughton on February 17th, 1741, in a fairground booth on Tottenham Court Road. Here’s how Captain John Godfrey, a former student of James Figg’s who in 1747 published his recollections of the early days of boxing in the Treatise Upon the Useful Science of Defence, describes the match:

One of Figg’s students was Jack Broughton, a waterman whose well-muscled physique was first built rowing paying passengers across the Thames. Broughton beat all comers and claimed the title of Champion of England at the Heavyweight from 1738, when he defeated Figg’s successor George Taylor, to 1750. One of those comers was George “The Coachman” Stevenson, who went up against Broughton on February 17th, 1741, in a fairground booth on Tottenham Court Road. Here’s how Captain John Godfrey, a former student of James Figg’s who in 1747 published his recollections of the early days of boxing in the Treatise Upon the Useful Science of Defence, describes the match:

I saw [George Stevenson] fight BROUGHTON, for forty Minutes. BROUGHTON I knew to be ill at that Time; besides it was a hasty made Match, and he had not that Regard for his Preparation, as he afterwards found he should have. But here his true Bottom was proved, and his Conduct shone. They fought in one of the Fair-Booths at Tottenham Court, railed at the End toward the Pit. After about thirty-five Minutes, being both against the Rails, and scrambling for a Fall, BROUGHTON got such a Lock upon him as no Mathematician could have devised a better. There he held him by this artificial Lock, depriving him of all Power of Rising or Falling, till resting his Head for about three or four Minutes on his Back, he found himself recovering. Then loosed the Hold, and on setting to again, he hit the Coachman as hard a Blow as any he had given him in the whole Battle; that he could no longer stand, and his brave contending Heart, though with Reluctance, was forced to yield. The Coachman is a most beautiful Hitter; he put in his Blows faster than BROUGHTON, but then one of the latter’s told for three of the former’s. Pity – so much Spirit should not inhabit a stronger Body!

A few days later Stevenson was dead. Funded by the Duke of Cumberland, Broughton opened a new amphitheater on March 10, 1743. The tragedy of Stevenson’s death by his hand inspired him to promulgate a code of behavior in his new arena “for the better regulation of the amphitheater, and approved of by the gentle men, and agreed to by the pugilists.” These were the first restrictions placed upon prizefighters. Broughton’s Rules were minimal compared to the rules today, but they introduced key concepts of fair play still in use.

A few days later Stevenson was dead. Funded by the Duke of Cumberland, Broughton opened a new amphitheater on March 10, 1743. The tragedy of Stevenson’s death by his hand inspired him to promulgate a code of behavior in his new arena “for the better regulation of the amphitheater, and approved of by the gentle men, and agreed to by the pugilists.” These were the first restrictions placed upon prizefighters. Broughton’s Rules were minimal compared to the rules today, but they introduced key concepts of fair play still in use.

I. That a square of a yard be chalked in the middle of the stage, and on every fresh set-to after a fall, or being parted form the rails, each Second is to bring his Man to the side of the square, and place him opposite to the other, and till they are fairly set-to at the Lines, it shall not be lawful for one to strike at the other.

II. That, in order to prevent any Disputes, the time a Man lies after a fall, if the Second does not bring his Man to the side of the square, within the space of half a minute, he shall be deemed a beaten Man.

III. That in every main Battle, no person whatever shall be upon the Stage, except the Principals and their Seconds, the same rule to be observed in bye-battles, except that in the latter, Mr. Broughton is allowed to be upon the Stage to keep decorum, and to assist Gentlemen in getting to their places, provided always he does not interfere in the Battle; and whoever pretends to infringe these Rules to be turned immediately out of the house. Every body is to quit the Stage as soon as the Champions are stripped, before the set-to.

IV. That no Champion be deemed beaten, unless he fails coming up to the line in the limited time, or that his own Second declares him beaten. No Second is to be allowed to ask his man’s Adversary any questions, or advise him to give out.

V. That in bye-battles, the winning man to have two-thirds of the Money given, which shall be publicly divided upon the Stage, notwithstanding any private agreements to the contrary.

VI. That to prevent Disputes, in every main Battle the Principals shall, on coming on the Stage, choose from among the gentlemen present two Umpires, who shall absolutely decide all Disputes that may arise about the Battle; and if the two Umpires cannot agree, the said Umpires to choose a third, who is to determine it.

VII. That no person is to hit his Adversary when he is down, or seize him by the ham, the breeches, or any part below the waist: a man on his knees to be reckoned down.

That rule number VII has two concepts that have become idioms for fair play: don’t hit a man when he’s down and no hitting below the belt. Broughton’s Rules would remain the operating rules of boxing until they were expanded into the London Prize Ring Rules in 1838. Those were then superseded by the Marquess of Queensberry rules in 1867.