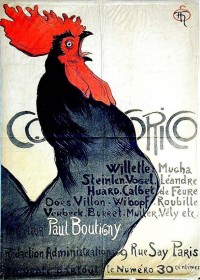

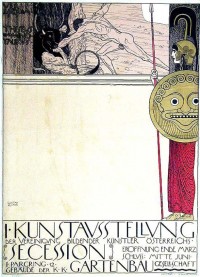

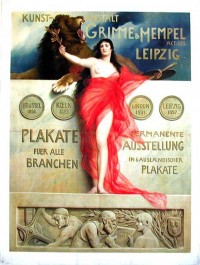

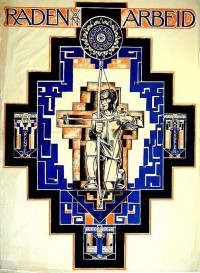

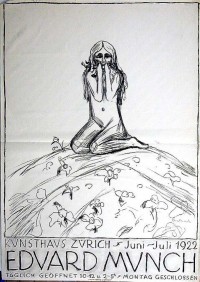

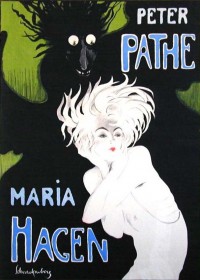

Just ten months ago after seven years of litigation, the Federal Court of Justice in Karlsruhe, Germany, ruled that 4,529 rare turn of the century posters collected by Hans Sachs before he and his family fled Germany in 1939 belonged to Sachs’ son Peter. Hans Sachs, a dentist with an unfailing eye and unquenchable thirst for graphic art, had amassed 12,500 posters starting when he was a teenager in the late 1890s right through to the precipice of World War II. His collection, replete with small print run rarities, political propaganda, sports events, advertising for movies, operas, art exhibits and consumer goods, some of them by masters like Toulouse-Lautrec and Gustav Klimt, was the biggest and best in Germany, probably in the world.

Just ten months ago after seven years of litigation, the Federal Court of Justice in Karlsruhe, Germany, ruled that 4,529 rare turn of the century posters collected by Hans Sachs before he and his family fled Germany in 1939 belonged to Sachs’ son Peter. Hans Sachs, a dentist with an unfailing eye and unquenchable thirst for graphic art, had amassed 12,500 posters starting when he was a teenager in the late 1890s right through to the precipice of World War II. His collection, replete with small print run rarities, political propaganda, sports events, advertising for movies, operas, art exhibits and consumer goods, some of them by masters like Toulouse-Lautrec and Gustav Klimt, was the biggest and best in Germany, probably in the world.

He was a pioneer in the recognition of the value of the graphic arts, and in an era when posters were meant to be stuck to a wall and torn down or covered up a few days later, he treated his collection like a fine gallery of oil paintings. He put his money where his mouth was, too. He had an addition built to his home to house the collection and opened it to the public as the Museum of Applied Arts.

The rise of the Nazi party ruined all this. In the summer of 1938, the poster collection was confiscated by Joseph Goebbels who coveted the art for a museum of his own. A few months later, on November 9th, 1938, during the infamous Kristallnacht pogrom against the Jews, Hans Sachs was arrested and sent to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp outside of Berlin. Thanks to the tireless efforts of his wife Felicia in securing visas to England, he was released three weeks later. Together with his wife and one-year-old son Peter, Hans fled to London and from then to New York.

The rise of the Nazi party ruined all this. In the summer of 1938, the poster collection was confiscated by Joseph Goebbels who coveted the art for a museum of his own. A few months later, on November 9th, 1938, during the infamous Kristallnacht pogrom against the Jews, Hans Sachs was arrested and sent to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp outside of Berlin. Thanks to the tireless efforts of his wife Felicia in securing visas to England, he was released three weeks later. Together with his wife and one-year-old son Peter, Hans fled to London and from then to New York.

When the war was over, Hans assumed his collection could not have survived, so he applied for a refund under West German’s compensation program. In 1961, he received 225,000 German marks (about $50,000 at that time). Five years later, Sachs discovered that as many as 8,000 of his posters had indeed survived the war but were squirreled away in an East German museum. His attempts to share his knowledge with the museum were rebuffed and Hans died in 1974 never having laid eyes on his beloved collection again.

After reunification, the collection, now reduced to 5,000 pieces (no one knows what happened to the rest), was moved to the German Historical Museum in Berlin where it was kept in storage. Only scholars were allowed access to it. Peter Sachs had no idea a considerable chunks of the collection had survived until 2005. He immediately initiated a campaign to get the posters back. He offered to repay the compensation, now tip money compared to the market value of the rare collection, and took the museum to court.

After reunification, the collection, now reduced to 5,000 pieces (no one knows what happened to the rest), was moved to the German Historical Museum in Berlin where it was kept in storage. Only scholars were allowed access to it. Peter Sachs had no idea a considerable chunks of the collection had survived until 2005. He immediately initiated a campaign to get the posters back. He offered to repay the compensation, now tip money compared to the market value of the rare collection, and took the museum to court.

Because his father had accepted the money, the courts consistently ruled that Peter had no legal grounds to reclaim the posters. The final court of appeals overruled those letter-of-the-law judgments because even though it was true that technically the posters now belonged to Germany, the whole point of compensation laws was to redress the injustices of the Nazi regime. Thus the court ruled in Peter’s favor in the interest in justice.

When the story broke last year, one of Peter Sachs’ lawyers, Matthias Druba said: “Hans Sachs wanted to show the poster art to the public, so the objective now is to find a depository for the posters in museums where they can really be seen and not hidden away.” That objective is no longer. I don’t know what kind of effort he made to place the entire collection in the past 10 months, but apparently he was unable to find any takers so instead he’s going to sell the vast majority of it.

When the story broke last year, one of Peter Sachs’ lawyers, Matthias Druba said: “Hans Sachs wanted to show the poster art to the public, so the objective now is to find a depository for the posters in museums where they can really be seen and not hidden away.” That objective is no longer. I don’t know what kind of effort he made to place the entire collection in the past 10 months, but apparently he was unable to find any takers so instead he’s going to sell the vast majority of it.

Starting tomorrow and going through Sunday, 1,233 of the posters will go under the hammer at Bohemian National Hall in New York City. Guernsey’s Auctions is handling the sale, and you can bid online via Live Auctions (day one here, day two here, day three here). Thousands more will be sold at later auctions planned for September and next January.

Peter Sachs will be keeping exactly four posters with sentimental value for himself and plans to donate another 800 or so to museums. He’s entirely content with this decision.

Peter Sachs will be keeping exactly four posters with sentimental value for himself and plans to donate another 800 or so to museums. He’s entirely content with this decision.

“There’s of course no practical way that I could frame and hang 4,300 posters, so I just didn’t see any other alternative than to do what we’re doing,” Peter Sachs, 75, said by telephone from his home in Las Vegas. “But I don’t feel guilty in any way whatsoever — even with them being auctioned I think it’s far preferable that they will wind up in the hands of people who truly enjoy them and appreciate them rather than sitting in a museum’s storage for another 70 years without seeing the light of day.”

Yes well, that’s debatable, I suppose. Researchers who will now have to visit a few thousand collectors and museums all over the world to view a collection that was once in a single museum might beg to differ. There’s  no question what his father’s position on the issue would have been. He kept his collection together even under the unspeakable duress of the Nuremberg Laws and volunteered to help the museum that was keeping it hidden behind the Iron Curtain.

no question what his father’s position on the issue would have been. He kept his collection together even under the unspeakable duress of the Nuremberg Laws and volunteered to help the museum that was keeping it hidden behind the Iron Curtain.

Sachs has reimbursed the German government for the 225,000 marks compensation payment, and why not? The full 4,300 poster collection is valued at between $6 million and $21 million, so Mr. Sachs is looking at quite the plush retirement.

The only bright side to this, and it ain’t much of one, is that at least we get to see the collection in pictures via the online catalogs. There’s also a print catalog available for $52 that has pictures of all the posters being sold this weekend.