Julia Pastrana was born in Sinaloa, Mexico, in 1834, with two congenital diseases that would be her fortune and her curse. Generalized hypertrichosis lanuginosa caused her face and body to be covered in long, straight, thick black hair, her jaw to jut out and her ears and nose to be disproportionately large; gingival hyperplasia thickened her lips and gums.

Julia Pastrana was born in Sinaloa, Mexico, in 1834, with two congenital diseases that would be her fortune and her curse. Generalized hypertrichosis lanuginosa caused her face and body to be covered in long, straight, thick black hair, her jaw to jut out and her ears and nose to be disproportionately large; gingival hyperplasia thickened her lips and gums.

The circumstances of her childhood are unclear, muddled by later promotional legends. According to A Cabinet of Medical Curiosities a book by Dr. Jan Bondeson whose cover Julia graces, she was found in a cave when she was two years old being cared for by a so-called root-digging Indian named Espinosa who insisted the child was not hers. She did love her, though, and raised her until her death. When Espinosa died, the governor of Sinaloa took Julia on as a servant. It wasn’t charity that inspired his actions; he wanted to study her as a medical curiosity.

Tired of being mistreated, Julia left his employ in 1854. According to some sources she was bought as a circus sideshow — slavery was illegal but circus exhibits were still bought and sold — by a Mexican customs agent who took her to the United States. American impresario M. Rates claimed he found her in Mexico and convinced her to go on the sideshow circuit in North America. He exhibited her as the “Marvelous Hybrid or Bear Woman” and she was a sensation. Doctors examined her, declaring her a human-orangutan hybrid and a new species of animal altogether.

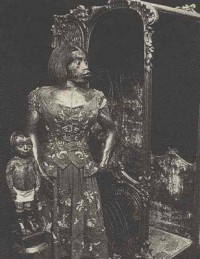

She had a lovely soprano voice and a petite figure (she was just four feet, five inches tall) with tiny hands and feet. She was a nimble and graceful dancer. Her singing and dancing were often mentioned in surprised tones for their quality and elegance. Her mind was also far from brutish. She spoke three languages and was by all accounts a kind, warm, intelligent person, an excellent conversationalist and a generous donor to charitable causes. She was also punctilious about her appearance. It may have been monetized by its association with beasts of the wild, but she always made sure her hair was elaborately coiffed and her dresses pretty and feminine albeit very short for Victorian sensibilities.

In New York she met a Theodore Lent. He married her and became her manager, doubtless the former was a means to secure the latter. He brought her to Europe where she was a great success. Lent made sure she had very little in the way of society, despite her yearning for friends and affection, out of fear that if people knew she was a gentle, well-read, fully human woman, her shows wouldn’t sell as well.

She got pregnant during the European tour. They were in Moscow in 1860 when she went into labour. Her son Theodore was born with hypertrichosis and only lived 35 hours. Julia died from a birth-related fever a few days later. Her last words were reportedly “I die happy; I know I have been loved for myself.”

Unfortunately, her husband put the lie to those sad final words. He showed his true disgusting colors after the death of his wife and child by either selling their bodies to a Russian anatomy professor for £500 and then buying them back for £800 after they were embalmed when he realized he could still profit off of them, or by having them embalmed and taking them on the road. He nailed the feet of his wife and little baby to boards with poles so they could be displayed standing up. Then he married a bearded lady whom he named Zenora Pastrana and billed her as Julia’s sister. He and his new wife traveled Europe on exhibit next to the corpses of his dead wife and child.

Unfortunately, her husband put the lie to those sad final words. He showed his true disgusting colors after the death of his wife and child by either selling their bodies to a Russian anatomy professor for £500 and then buying them back for £800 after they were embalmed when he realized he could still profit off of them, or by having them embalmed and taking them on the road. He nailed the feet of his wife and little baby to boards with poles so they could be displayed standing up. Then he married a bearded lady whom he named Zenora Pastrana and billed her as Julia’s sister. He and his new wife traveled Europe on exhibit next to the corpses of his dead wife and child.

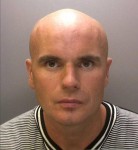

In 1921, Julia and little Theodore’s bodies were purchased by Earl Jaeger Lund, a Norwegian show promoter who put them on display at his amusement park and on tours until the 1970s. Finally in 1972 there was enough of an outcry about this horrendous spectacle that the remains were put in storage at the Oslo fairground. They saw even more mistreatment out of the public eye. Vandals broke in and damaged Julia’s body in 1976, and threw the baby’s body into a ditch where it was devoured by mice. In 1979, Julia’s body was stolen only to be recovered shortly thereafter in a suburban garbage dump, her arm severed.

After it was recovered, Julia’s body was moved to the Institute of Forensic Medicine at the Oslo University Hospital where it remained in storage from 1997 until now.

In 2005, Mexican artist Laura Anderson Barbata, then in Oslo for a residency, began to campaign for Julia Pastrana’s body to be returned to Mexico for the proper Catholic burial that had so long been denied her. It took years before she got some attention, but in 2008 she submitted paperwork in favor of Julia’s repatriation to Norway’s National Committee for the Evaluation of Research on Human Remains. Last year the committee admitted that it was unlikely Julia Pastrana would have wanted to end up a specimen.

There were still some hoops to jump through. The University was amenable to returning the body, but they weren’t comfortable just handing her over to Laura Barbata because she was the only one who had asked.

A breakthrough came after the current governor of Sinaloa, Mario López Valdez, joined Ms. Barbata’s cause last year and petitioned for Pastrana’s repatriation. The Mexican ambassador to Denmark, Norway and Iceland, Martha Bárcena Coqui, offered to work with the university to accept the body.

“We understood that she must have suffered enormously during her lifetime and that her remains did not receive the respect they deserved for many years,” Ms. Coqui said by e-mail.

The institute agreed to begin the process of transferring Ms. Pastrana to Mexican custody last August.

Last Thursday, Barbata confirmed Julia’s identity before her body was sealed in a coffin. On Tuesday, Julia’s mortal remains were finally laid to rest in a cemetery in Sinaloa de Leyva. It’s touching to see crowds of people attending her funeral and her white coffin covered with flowers. Her last show was finally worthy of the person she was.