UC Santa Barbara archaeologists excavating the south-central Andean province of Andahuaylas, Peru, have unearthed the remains of 32 people whose skulls bear the tell-tale signs of 45 different trepanations. Nine out of the 32 had more than one hole drilled or cut into their skulls. The burials date to the Late Intermediate Period (ca. 1,000-1,250 A.D.), a time of great upheaval following the collapse of the Wari Empire.

UC Santa Barbara archaeologists excavating the south-central Andean province of Andahuaylas, Peru, have unearthed the remains of 32 people whose skulls bear the tell-tale signs of 45 different trepanations. Nine out of the 32 had more than one hole drilled or cut into their skulls. The burials date to the Late Intermediate Period (ca. 1,000-1,250 A.D.), a time of great upheaval following the collapse of the Wari Empire.

“For about 400 years, from 600 to 1000 AD, the area where I work — the Andahuaylas — was living as a prosperous province within an enigmatic empire known as the Wari,” [UC Santa Barbara bioarchaeologist Danielle Kurin] said. “For reasons still unknown, the empire suddenly collapsed.” And the collapse of civilization, she noted, brings a lot of problems.

“But it is precisely during times of collapse that we see people’s resilience and moxie coming to the fore,” Kurin continued. “In the same way that new types of bullet wounds from the Civil War resulted in the development of better glass eyes, the same way IED’s are propelling research in prosthetics in the military today, so, too, did these people in Peru employ trepanation to cope with new challenges like violence, disease and depravation 1,000 years ago.”

Earlier studies have found that trepanation was frequently used in response to blunt force wounds. One noted that holes were drilled over or next radiating fractures from trauma in 44% of cases, and that figure may be low because the trepanation could easily obscure the evidence of blunt force trauma if the damaged bone was all removed. It follows, therefore, that times of conflict would see an increase in cranial surgery simply because there are more wounds to be treated.

Earlier studies have found that trepanation was frequently used in response to blunt force wounds. One noted that holes were drilled over or next radiating fractures from trauma in 44% of cases, and that figure may be low because the trepanation could easily obscure the evidence of blunt force trauma if the damaged bone was all removed. It follows, therefore, that times of conflict would see an increase in cranial surgery simply because there are more wounds to be treated.

That’s not to say that there blunt trauma was the only condition trepanation was prescribed for. Any cranial affliction from an infection to swelling to a persistent headache could be dealt with via skull drilling surgery. Not everyone was a candidate, however. There was a cultural taboo in the Andahuaylas against trepanning the skulls of women and children. Out of the 32 skulls found, 25 of them are male and only three female (there are four adults whose gender could not be established.)

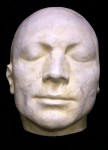

The skulls Kurin’s team found displayed a variety of different trepanation techniques: scraping, cutting and hand drilling. In some cases they were administered post-mortem and are clearly experiments just like cadaver studies in med schools today.

“As bioarchaeologists, we can tell that they’re experimenting on recently dead bodies because we can measure the location and depths of the holes they’re drilling,” [Kurin] continued. “In one example, each hole is drilled a little deeper than the last. So you can imagine a guy in his prehistoric Peruvian medical school practicing with his hand drill to know how many times he needs to turn it to nimbly and accurately penetrate the thickness of a skull.”

It’s a fascinating picture:

The top inset photograph is of the side of the skull where a previous trepanation had been successful enough to allow bone regrowth. So this fellow had it done, it worked for at least a time, then when he died he left his body to science (or science just took it) and became a drill depth tester.

A mummified skull provided a glimpse into the treatment. It has a scraped trepanation on the posterior right parietal bone that was in the process of healing at the time of death. This area has no long hair, unlike the rest of the scalp, and under a microscope it looks cleanly cut. The fellow shaved or was shaved to keep the wound site clean and free of infection. He also has a small second hole, this one bored into the bone, on his forehead. It’s in an area associated with migraine pain, just the kind of thing you might to drill a hole in your skull to treat. There is no post-surgical bone growth, so either the patient did not survive the surgery or he too was a port-mortem experiment. There are, however, the remains of a dark substance over the bore hole, a thick sludge with a finger print embedded in it. Archaeologists believe it may be the leftovers of an herbal poultice.

A mummified skull provided a glimpse into the treatment. It has a scraped trepanation on the posterior right parietal bone that was in the process of healing at the time of death. This area has no long hair, unlike the rest of the scalp, and under a microscope it looks cleanly cut. The fellow shaved or was shaved to keep the wound site clean and free of infection. He also has a small second hole, this one bored into the bone, on his forehead. It’s in an area associated with migraine pain, just the kind of thing you might to drill a hole in your skull to treat. There is no post-surgical bone growth, so either the patient did not survive the surgery or he too was a port-mortem experiment. There are, however, the remains of a dark substance over the bore hole, a thick sludge with a finger print embedded in it. Archaeologists believe it may be the leftovers of an herbal poultice.

The group of skulls has already proven a treasure trove of information, and will likely yield more in the years to come. It is the largest well-contextualized collection of trepanned skulls in the world. There are plenty of holey crania in museums and institutions, but they were gathered a century ago under conditions that would make any archaeologist today shudder. There is little information about the sites where they were discovered and all-important contextual issues weren’t investigated or recorded.

The group of skulls has already proven a treasure trove of information, and will likely yield more in the years to come. It is the largest well-contextualized collection of trepanned skulls in the world. There are plenty of holey crania in museums and institutions, but they were gathered a century ago under conditions that would make any archaeologist today shudder. There is little information about the sites where they were discovered and all-important contextual issues weren’t investigated or recorded.

But thanks to Kurin’s careful archaeological excavation of intact tombs and methodical analysis of the human skeletons and mummies buried therein, she knows exactly where, when and how the remains she found were buried, as well as who and what was buried with them. She used radiocarbon dating and insect casings to determine how long the bodies were left out before they skeletonized or were mummified, and multi-isotopic testing to reconstruct what they ate and where they were born. “That gives us a lot more information,” she said.

“These ancient people can’t speak to us directly, but they do give us information that allows us to reconstruct some aspect of their lives and their deaths and even what happened after they died,” she continued. “Importantly, we shouldn’t look at a state of collapse as the beginning of a ‘dark age,’ but rather view it as an era that breeds resilience and foments stunning innovation within the population.”

The British Library has released more than one million high resolution images scanned from public domain books from the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries on their Flickr account. Scanned as part of a digitization collaboration with Microsoft that began in 2008, the images illustrate a vast range of topics from literary classics like Charles Dickens novels to anthropological studies, travel guides, histories, song collections, children’s books and ever so much more. Even those decorative swirls that separate chapters and fancy initial capitals made the cut.

The British Library has released more than one million high resolution images scanned from public domain books from the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries on their Flickr account. Scanned as part of a digitization collaboration with Microsoft that began in 2008, the images illustrate a vast range of topics from literary classics like Charles Dickens novels to anthropological studies, travel guides, histories, song collections, children’s books and ever so much more. Even those decorative swirls that separate chapters and fancy initial capitals made the cut.We plan to launch a crowdsourcing application at the beginning of next year, to help describe what the images portray. Our intention is to use this data to train automated classifiers that will run against the whole of the content. The data from this will be as openly licensed as is sensible (given the nature of crowdsourcing) and the code, as always, will be under an open licence.

Since the images are public domain, they can be used without conditions. At the very least it’s a huge free stock collection that I can envision coming in very handy for everyone from graphic designers to parents looking to make an extremely nerdy coloring book for their kids (or themselves; coloring is the best). The British Library wants to know how people are using the pictures and they’ve offered their enthusiastic collaboration with any project readers may devise. You can Email or tweet them with any questions or ideas.

Since the images are public domain, they can be used without conditions. At the very least it’s a huge free stock collection that I can envision coming in very handy for everyone from graphic designers to parents looking to make an extremely nerdy coloring book for their kids (or themselves; coloring is the best). The British Library wants to know how people are using the pictures and they’ve offered their enthusiastic collaboration with any project readers may devise. You can Email or tweet them with any questions or ideas.