Researchers from Swansea University in Wales and the KU Leuven University in Belgium have identified a carving of Roman emperor Claudius as a pharaoh participating in an ancient ritual for the fertility god Min on the western wall of the temple of Shanhur about 12 miles north of Luxor. The temple dates to the Roman era. It was first built as a temple to Isis under Augustus but the carvings on the western and eastern exterior walls, 36 on each, were all done during the reign of the emperor Claudius (41-54 A.D.).

Researchers from Swansea University in Wales and the KU Leuven University in Belgium have identified a carving of Roman emperor Claudius as a pharaoh participating in an ancient ritual for the fertility god Min on the western wall of the temple of Shanhur about 12 miles north of Luxor. The temple dates to the Roman era. It was first built as a temple to Isis under Augustus but the carvings on the western and eastern exterior walls, 36 on each, were all done during the reign of the emperor Claudius (41-54 A.D.).

The carvings were first exposed during an archaeological excavation in 2000-2001. Before that they had been covered by a mound of soil that obscured and protected the exterior temple walls, leaving the carvings in excellent condition. In the decade or so since they lost the protection of the mound, the carvings, made on lower grade limestone that is highly susceptible to erosion, have unfortunately been weathered so they’re much harder to make out now. The Swansea-KU Leuven team began recording and translating the exterior wall carvings in 2010.

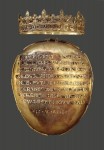

It’s scene 123 on the western wall that is the stand-out piece, both in terms of preservation and historical significance. It depicts Claudius doing the ritual of the raising of the pole for Min, the Egyptian god of fertility and power. This ritual is ancient, going back 4,300 years to the Old Kingdom, which we know from the 32 extant scenes of the pole-raising that have been found. What makes this one so special is not just the involvement of Clau-Clau-Claudius (if you haven’t seen I, Claudius, please do so immediately; there will be a test), but the fact that the inscriptions include a precise date when this particular ritual took place. It’s the only one of the 32 that does.

It’s scene 123 on the western wall that is the stand-out piece, both in terms of preservation and historical significance. It depicts Claudius doing the ritual of the raising of the pole for Min, the Egyptian god of fertility and power. This ritual is ancient, going back 4,300 years to the Old Kingdom, which we know from the 32 extant scenes of the pole-raising that have been found. What makes this one so special is not just the involvement of Clau-Clau-Claudius (if you haven’t seen I, Claudius, please do so immediately; there will be a test), but the fact that the inscriptions include a precise date when this particular ritual took place. It’s the only one of the 32 that does.

The scene shows Claudius garbed in pharaonic regalia. He wears a complex crown known as the “Roaring One” made out of three rushes embellished by sun discs and solarized falcons. The rushes are flanked by ostrich feathers and perched on ram horns. He carries two ceremonial staffs in his left hand and a scepter in his right. The accompanying inscription identifies him and dates the ritual:

King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Lord of the Two Lands, Tiberios Klaudios

Son of Ra, Lord of the Crowns, Kaisaros Sebastos Germanikos Autokrator

Raising the pole of the tent/cult chapel for his father in month 2 of the smw-season (Payni), day 19.

Min stands across from Claudius, facing him. He holds a flail and wears a double feather crown with sun disc. As is customary for this fertility god, he also sports a magnificent erection. Behind him is his cult chapel and between him and Claudius eight men enact the ritual by climbing four poles propped against a central a pole topped by a crescent moon.

The inscriptions and iconography suggest that by performing this ritual, Claudius assumes the formidable characteristics of Min:

[Words spoken by Min (or Min-Ra)… Lord of?] Coptos, Lord of Panopolis (Akhmim), who is on top of his stairway,

[…] King of the gods, strong sovereign, who captures

[…] who roars when he rages, lord of fear,

[…] the one who brings into control the warhorses, whose fear is in the Two Lands,

[…] about whose beauty one boasts, who inflicts terror/scares away with his strength.

He’s not roaring with rage at Claudius, though, thanks to the pole-raising. By executing the ritual, Claudius keeps the cult of Min alive and asserts his power over “the (southern) foreign lands” which, according to the inscription, Min gives to him.

The inclusion of a date indicates that this ritual event actually happened, although Claudius himself was not present in person. He never went to Egypt. A priest probably acted as his proxy, something that was common even in the pharaonic era since the king couldn’t possibly be present for every ritual.

There’s another Claudius-Min ritual carved in the exterior eastern wall. In this one Claudius makes an offering of lettuce to Min and Horus the Child. The lettuce symbolizes Egypt’s crops which will be made abundant thanks to Min and his prodigious endowment.

There’s another Claudius-Min ritual carved in the exterior eastern wall. In this one Claudius makes an offering of lettuce to Min and Horus the Child. The lettuce symbolizes Egypt’s crops which will be made abundant thanks to Min and his prodigious endowment.

[Take for] you the lettuce (|n) in order to unite it with your body (or phallus) and lettuce in order to make procreative [your] phallus

You can read the whole paper here if you register (registration is free).