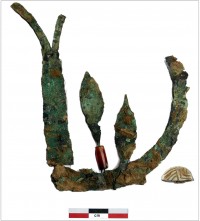

This past August, kiln workers discovered human skeletal remains while digging for clay to make bricks in the village of Chandayan, Uttar Pradesh, northern India. The skeleton was wearing a crown, a copper strip with two copper leaves attached to it decorated with a tubular carnelian bead and a faience one. They also found a redware (terracotta) bowl with a collared rim, a miniature pot and a clay sling ball. The local residents were so excited by the discovery that they, along with the police, protected the site, stopping further clay digging.

This past August, kiln workers discovered human skeletal remains while digging for clay to make bricks in the village of Chandayan, Uttar Pradesh, northern India. The skeleton was wearing a crown, a copper strip with two copper leaves attached to it decorated with a tubular carnelian bead and a faience one. They also found a redware (terracotta) bowl with a collared rim, a miniature pot and a clay sling ball. The local residents were so excited by the discovery that they, along with the police, protected the site, stopping further clay digging.

Word of the find spread over the region, eventually catching the interest of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) which dispatched an archaeological team to Chandayan. They excavated the burial site and found more of the skeleton — a pelvic bone, the left femur — as well as another piece of th crown, potsherds and 21 earthenware pots including storage jars and dish-on-stands. Most of them are plain redware, but there is a grey vessel and some lightly decorated pieces.

About 65 feet away from the burial at the same depth, the team discovered animal bones and more earthenware pots. Archaeologists believe the animal may have been sacrificed during the funerary rites for the crowned person. Another 150 feet from the burial they found evidence of an ancient home: a compacted earth floor, mud walls and postholes.

Carnelian, glazed faience, sling balls and collared pots are artifacts typical of the late Indus Valley (also known as Harappan after the type site discovered in the 1920s) civilization. In fact, work in carnelian and copper metallurgy were innovations introduced in the Indus Valley civilization. The late Indus Valley phase was from 1900 to 1600 B.C., and although burial sites from this period have been found in Uttar Pradesh, this is the first evidence of a habitation site. The crown is also a unique piece. A silver crown from the late Indus Valley period has been found before, but not a copper one.

Carnelian, glazed faience, sling balls and collared pots are artifacts typical of the late Indus Valley (also known as Harappan after the type site discovered in the 1920s) civilization. In fact, work in carnelian and copper metallurgy were innovations introduced in the Indus Valley civilization. The late Indus Valley phase was from 1900 to 1600 B.C., and although burial sites from this period have been found in Uttar Pradesh, this is the first evidence of a habitation site. The crown is also a unique piece. A silver crown from the late Indus Valley period has been found before, but not a copper one.

The crown suggests that the skeleton belonged to someone of importance, perhaps the village chieftain or local leader of some kind. The crudeness of the pottery and the local flavor of the decoration (none of them decorated with the precision and elaborate geometries that make Indus Valley pottery so popular in museums) suggest he was a big fish in a small pond rather than a ruler of a large territory who would have had access to more expensive trade goods. The crown could have had another function or perhaps was merely decorative, so the deceased may have been someone with extravagant taste in jewelry rather than a dominant political figure.

Although with a range of 930,000 square miles it covered far more area than the other great Bronze Age civilizations (Egypt, Mesopotamia and China), the Indus script has yet to be deciphered so there’s still so much we don’t know about the Indus Valley civilization. The large urban centers that have been unearthed are impressive in their meticulous planning, water delivery and drainage systems, public baths, public buildings, residential areas distinct from administrative and/or religious compounds. More than a thousand towns from major cities like Harappa and Mohenjo-daro to small settlements have been found but only about a hundred of them have been excavated. The Chandayan settlement is the easternmost one found yet.