A gilt copper plate that was placed over Oliver Cromwell’s chest when he was laid to rest in his coffin sold at a Sotheby’s auction last month for £74,500 ($116,719), six times its pre-sale estimate of £8,000 – £12,000. Bidding started at the low estimate and rapidly increased in increments of thousands. The hammer price was £60,000 (the rest of the cost is the buyer’s premium) and the buyer, who was in the room, is anonymous.

A gilt copper plate that was placed over Oliver Cromwell’s chest when he was laid to rest in his coffin sold at a Sotheby’s auction last month for £74,500 ($116,719), six times its pre-sale estimate of £8,000 – £12,000. Bidding started at the low estimate and rapidly increased in increments of thousands. The hammer price was £60,000 (the rest of the cost is the buyer’s premium) and the buyer, who was in the room, is anonymous.

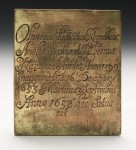

The plaque is 6.5″ by 5.5″ and is engraved on both sides. The front is engraved with the coat of arms of the Protectorate — the flags of England, Scotland, Ireland with Cromwell’s personal arms, an argent lion rampant borrowed from the arms of his ancestors the Princes of Powys, on an inescutcheon in the center, a crowned English lion supporting the left and the Welsh red dragon (a replacement for the Scottish unicorn James I had placed on the Royal Arms) supporting the right — and the motto “Pax quaeritur bello,” meaning “Peace is sought by war.” The inscription on the back gives Cromwell’s vital statistics: “Oliver Protector of the Republic of England, Scotland and Ireland. Born 25 April year 1599. Inaugurated 16 December 1653. Died 3 September year 1658. Here he lies.”

The plaque is 6.5″ by 5.5″ and is engraved on both sides. The front is engraved with the coat of arms of the Protectorate — the flags of England, Scotland, Ireland with Cromwell’s personal arms, an argent lion rampant borrowed from the arms of his ancestors the Princes of Powys, on an inescutcheon in the center, a crowned English lion supporting the left and the Welsh red dragon (a replacement for the Scottish unicorn James I had placed on the Royal Arms) supporting the right — and the motto “Pax quaeritur bello,” meaning “Peace is sought by war.” The inscription on the back gives Cromwell’s vital statistics: “Oliver Protector of the Republic of England, Scotland and Ireland. Born 25 April year 1599. Inaugurated 16 December 1653. Died 3 September year 1658. Here he lies.”

He didn’t lie there for long. After his death from malarial fever, Cromwell’s body was embalmed and put in a lead anthropoid coffin which was sealed and then placed in an elaborately decorated wooden coffin. The coffin and an effigy of the Lord Protector dressed in velvet, gold lace and ermin accessorized with the Imperial crown, orb and scepter, lay in state at Somerset House from September 20th until early November. The funeral procession took place on November 23rd, but he had already been quietly interred at Westminster Abbey two weeks earlier because his body was poorly embalmed and the stench had become problematic two months after his death. After enough pomp and ceremony to rival any royal funeral (Cromwell’s was in fact modeled after the funerary ceremonies of James I), Cromwell was officially buried in a vault in the Henry VII Lady Chapel.

He didn’t lie there for long. After his death from malarial fever, Cromwell’s body was embalmed and put in a lead anthropoid coffin which was sealed and then placed in an elaborately decorated wooden coffin. The coffin and an effigy of the Lord Protector dressed in velvet, gold lace and ermin accessorized with the Imperial crown, orb and scepter, lay in state at Somerset House from September 20th until early November. The funeral procession took place on November 23rd, but he had already been quietly interred at Westminster Abbey two weeks earlier because his body was poorly embalmed and the stench had become problematic two months after his death. After enough pomp and ceremony to rival any royal funeral (Cromwell’s was in fact modeled after the funerary ceremonies of James I), Cromwell was officially buried in a vault in the Henry VII Lady Chapel.

Less than two years later, Charles I’s son was restored to the throne. Although on August 29th, 1660, the Cavalier Parliament passed the Indemnity and Oblivion Act pardoning almost everyone involved in the execution of Charles I, the 59 signatories of the king’s death warrant were specifically exempt from Charles II’s mercy. That fall, 10 of the regicides still living were tried, convicted and executed. The penalty for High Treason was to be hanged, drawn and quartered; ie, the condemned were tied to a horse and dragged to the gallows where they were hanged until almost dead, then disemboweled, castrated, beheaded and their bodies cut into four sections.

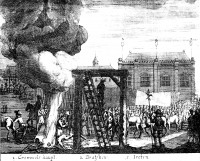

On December 4th, Parliament passed a bill of attainder posthumously declaring Oliver Cromwell, his son-in-law Henry Ireton and John Bradshaw, president of the High Court of Justice for the trial of King Charles I, guilty of High Treason. Bradshaw had died a month after Cromwell and was buried the day before him. Ireton had been dead and buried for nine years. All three were interred in the same chapel at Westminster Abbey. Parliament ordered the bodies exhumed and on January 30th, the 12th anniversary of Charles I’s execution, the corpses were dragged in their coffins to the west London execution site of Tyburn where their shrouded bodies were hanged. After hanging for an hour, the corpses were taken down, decapitated and the bodies tossed in a pit beneath the gallows. The heads were placed on 20-foot spikes in front of Westminster Hall where Charles I’s trial had taken place.

On December 4th, Parliament passed a bill of attainder posthumously declaring Oliver Cromwell, his son-in-law Henry Ireton and John Bradshaw, president of the High Court of Justice for the trial of King Charles I, guilty of High Treason. Bradshaw had died a month after Cromwell and was buried the day before him. Ireton had been dead and buried for nine years. All three were interred in the same chapel at Westminster Abbey. Parliament ordered the bodies exhumed and on January 30th, the 12th anniversary of Charles I’s execution, the corpses were dragged in their coffins to the west London execution site of Tyburn where their shrouded bodies were hanged. After hanging for an hour, the corpses were taken down, decapitated and the bodies tossed in a pit beneath the gallows. The heads were placed on 20-foot spikes in front of Westminster Hall where Charles I’s trial had taken place.

It was during this ugly process that the coffin plate was taken. It was “found in a leaden canister, lying on the breast of the corpse” by James Norfolke, Serjeant-at-Arms to the Speaker of the House of Commons, who had been tasked with exhuming the regicides’ bodies. He helped himself to the plaque and it remained in his family for hundreds of years until it was acquired by the Harcourt family in the 19th century. The sellers have chosen to remain anonymous so we don’t know if it’s been with the Harcourts since then or sold to another party at some point.

Either way, the plaque has had a much easier ride than Cromwell’s head. It stayed on its spike at Westminster Hall for close to 30 years. There are differing reports on what happened to it — blown down in a storm, surreptitiously removed in the dark of night — and the relic went underground until 1710 when it went on display at Claudius Du Puy’s private museum of curiosities in London. After Du Puy’s death, it passed through at least three more hands, including the Hughes brothers who again put it on macabre display, before being purchased by Josiah Henry Wilkinson in 1814. The Wilkinsons kept it in a velvet lined box, whipping it out for house guests to gasp over, for generations until Horace Wilkinson gave it to Cambridge University’s Sidney Sussex College, Cromwell’s alma mater, for proper burial in 1960. The burial was kept secret until 1962 and the exact location has never been revealed.

Either way, the plaque has had a much easier ride than Cromwell’s head. It stayed on its spike at Westminster Hall for close to 30 years. There are differing reports on what happened to it — blown down in a storm, surreptitiously removed in the dark of night — and the relic went underground until 1710 when it went on display at Claudius Du Puy’s private museum of curiosities in London. After Du Puy’s death, it passed through at least three more hands, including the Hughes brothers who again put it on macabre display, before being purchased by Josiah Henry Wilkinson in 1814. The Wilkinsons kept it in a velvet lined box, whipping it out for house guests to gasp over, for generations until Horace Wilkinson gave it to Cambridge University’s Sidney Sussex College, Cromwell’s alma mater, for proper burial in 1960. The burial was kept secret until 1962 and the exact location has never been revealed.