Before Samuel Morse developed the code that bears his name and patented the electromagnetic telegraph, he was a painter and a successful one at that. His teacher, Washington Allston, known today primarily for his Romantic landscapes, took the 20-year-old Samuel to study painting in England in 1811. In London he was admitted to the Royal Academy of Arts where instruction was focused on copying the works of the Renaissance Old Masters, drawing casts of ancient sculptures and live figure drawing. Morse’s works from this period were heavily influenced by the likes of Michelangelo and Raphael and were often mythological in theme, like 1812’s Dying Hercules.

Before Samuel Morse developed the code that bears his name and patented the electromagnetic telegraph, he was a painter and a successful one at that. His teacher, Washington Allston, known today primarily for his Romantic landscapes, took the 20-year-old Samuel to study painting in England in 1811. In London he was admitted to the Royal Academy of Arts where instruction was focused on copying the works of the Renaissance Old Masters, drawing casts of ancient sculptures and live figure drawing. Morse’s works from this period were heavily influenced by the likes of Michelangelo and Raphael and were often mythological in theme, like 1812’s Dying Hercules.

Morse and Allston spent four years in England as the War of 1812 raged. When Morse returned to the United States in 1815, he made a name for himself as a portrait painter, receiving commissions from wealthy socialites and dignitaries like former President John Adams and Revolutionary War hero Marquis de Lafayette. He hit the road again in 1830, traveling through Italy, Switzerland and France to learn from observing the original works of the Old Masters he had studied copies of in London.

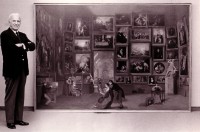

When he was in Paris in September of 1831, Morse conceived a monumental painting of the Salon Carré in the Louvre that would include dozens of the museum’s masterpieces. The works aren’t actually arranged in the one room when he painted them; this was a gallery picture, a fantasy arrangement of art in a single scene. Morse’s Gallery of the Louvre is the only major example of a gallery picture in American art history.

When he was in Paris in September of 1831, Morse conceived a monumental painting of the Salon Carré in the Louvre that would include dozens of the museum’s masterpieces. The works aren’t actually arranged in the one room when he painted them; this was a gallery picture, a fantasy arrangement of art in a single scene. Morse’s Gallery of the Louvre is the only major example of a gallery picture in American art history.

He squeezed 38 paintings and two sculptures from the Louvre collection into the six-by-nine-foot canvas, plus additional figures of museum visitors and copyists. Anthony Van Dyck and Titian have the most works on display with four apiece. Other artists represented are Tintoretto, Veronese, Leonardo da Vinci, Rubens, Poussin, Raphael, Rembrandt, Reni, Watteau, Correggio and Caravaggio. Click here (pdf) for a complete key to all the works and people in the painting.

He worked assiduously between September of 1831 and August of 1832 to copy the works he wished to include, some of which were positioned high on the walls. He built a moveable scaffold and lugged it around the vast halls of the Louvre so he could be at eye level with his subjects. Morse painting on his scaffold became something of a tourist draw in its own right. He also had to do a fair amount of math in composing this work. He had to calculate the proper scale and to figure out how they should be arranged on the canvas.

Then he had to put shoutouts to his people among the visitors. The trio in the back left corner are Morse’s good friend James Fenimore Cooper (who he hoped would buy the completed work) and Cooper’s wife and daughter. The woman sketching an art work in the center of the composition is Morse’s daughter, Susan Walker Morse. The man behind her giving her pointers is Morse himself. That sweet scene was symbolic of his purpose in creating this piece: to teach American artists and audiences about the important works of European art. He was also underscoring the value of a great public museum of art to artists and regular people, an institution that the United States lacked.

Then he had to put shoutouts to his people among the visitors. The trio in the back left corner are Morse’s good friend James Fenimore Cooper (who he hoped would buy the completed work) and Cooper’s wife and daughter. The woman sketching an art work in the center of the composition is Morse’s daughter, Susan Walker Morse. The man behind her giving her pointers is Morse himself. That sweet scene was symbolic of his purpose in creating this piece: to teach American artists and audiences about the important works of European art. He was also underscoring the value of a great public museum of art to artists and regular people, an institution that the United States lacked.

(Philadelphia’s Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts was founded in 1805 by artist and collector Charles Willson Peale, among others, but its collection at the time was casts of ancient sculptures. Coincidentally, the first major acquisition of the museum was a work by none other than Washington Allston: his monumental 1816 work The Dead Man Restored to Life by Touching the Bones of the Prophet Elisha. They had to mortgage the building to buy it.

The first public art museum in the United States was the Wadsworth Atheneum, founded in 1842 by Daniel Wadsworth, a great patrons of the arts, who seeded the new museum with many works from his personal collection.)

When the Louvre closed its doors for its yearly August vacation, Morse rolled up the canvas and packed it until his return to the United States in late 1832. He applied the finishing touches to the painting in late 1833 and exhibited the finished work in New York and New Haven. Morse hoped it would be a sensation, drawing huge crowds to pay the price of admission and securing him a much-desired commission for a painting in the Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol. It was not. The exhibitions lost money, and within a few years Morse had given up painting to focus on the telegraph.

It was purchased for much less than Morse had hoped in 1834 by George Hyde Clarke for his neoclassical mansion Hyde Hall in Ostego County, New York. After Clarke’s death, Gallery of the Louvre was purchased by former mayor of Albany John Townsend. From him it passed to his daughter Julia Townsend Munroe of Syracuse, New York. She loaned it to Syracuse University in 1884 and then donated it to the university in 1892. Ninety years later, Morse’s dream finally came true. Chicago businessman, art collector and founder of the Terra Foundation for American Art museum, Daniel J. Terra, Ronald Reagan’s Ambassador at Large for Cultural Affairs, bought Gallery of the Louvre from Syracuse University for $3.25 million, at that time the highest price ever paid for a piece of American art. It’s been at the Terra Foundation ever since.

It was purchased for much less than Morse had hoped in 1834 by George Hyde Clarke for his neoclassical mansion Hyde Hall in Ostego County, New York. After Clarke’s death, Gallery of the Louvre was purchased by former mayor of Albany John Townsend. From him it passed to his daughter Julia Townsend Munroe of Syracuse, New York. She loaned it to Syracuse University in 1884 and then donated it to the university in 1892. Ninety years later, Morse’s dream finally came true. Chicago businessman, art collector and founder of the Terra Foundation for American Art museum, Daniel J. Terra, Ronald Reagan’s Ambassador at Large for Cultural Affairs, bought Gallery of the Louvre from Syracuse University for $3.25 million, at that time the highest price ever paid for a piece of American art. It’s been at the Terra Foundation ever since.

In 2010 Gallery of the Louvre underwent a six-month conservation by experts in American painting restoration Lance Mayer and Gay Myers. They discovered that Morse was as inventive in his painting as he was in communication technology, sometimes to their chagrin. He mixed varnish and oil paint together instead of painting with oils and then sealing the canvas with varnish. This was problematic for the conservators because varnish discolors. When it’s a layer on top of the paint, it can be removed with appropriate solvents that won’t damage the oil paint beneath. When conservators did a solvent test on Gallery of the Louvre, they found that all of them damaged the combined varnish and paint.

The Terra Foundation documented the conservation with a video, A New Look: Samuel F. B. Morse’s “Gallery of the Louvre”, which is not available online in its entirety but there are six clips from it below.

[youtube=http://youtu.be/I3Of6rQoXUE?list=PL8B4264B7E8816952&w=430]

The conservation was successful, bringing out details that had become obscured over time. After it was complete, the painting was subject of three symposia — at the Yale University Art Gallery in April of 2011, the National Gallery in April of 2012 and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in April of 2013 — which generated scholarly essays on the work by art historians, professors, curators and conservators. Those essays have been published in a book that is a companion piece to a new traveling exhibition of the painting, Samuel F. B. Morse’s Gallery of the Louvre and the Art of Invention.

The exhibition opened Saturday at the Huntington Library in San Marino, California. It will be there until April before moving on to the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth, Texas (May 23rd, 2015 – September 7th, 2015), the Seattle Art Museum (September 22nd, 2015 – January 10th, 2016), the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas (January 2016 – April 2016), the Detroit Institute of Arts (June 2016 – September 2016), the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts (October 2016 – January 2017), the Reynolda House Museum of American Art in Winston-Salem, North Carolina (February 2017 – June 2017), the New Britain Museum of American Art in New Britain, Connecticut (June 2017 – October 2017), and finally the Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University in Stanford, California (November 2017 – January 2018).