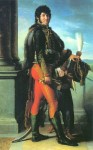

In his short life Joachim Murat rose from modest beginnings as an innkeeper’s son in the small southwestern French town of Labastide-Fortunière to the King of Naples at 41 years of age. In between he became one of Napoleon’s best generals and, after his marriage to Caroline Bonaparte, Prince and Grand Admiral of France and the Grand Duke of Berg. Famous for his daring cavalry charges and for his flamboyant dress sense involving as many buttons, gold tassels, medals and feathers as can be crammed onto a uniform, Murat fought in approximately 200 battles and looked great doing it.

In his short life Joachim Murat rose from modest beginnings as an innkeeper’s son in the small southwestern French town of Labastide-Fortunière to the King of Naples at 41 years of age. In between he became one of Napoleon’s best generals and, after his marriage to Caroline Bonaparte, Prince and Grand Admiral of France and the Grand Duke of Berg. Famous for his daring cavalry charges and for his flamboyant dress sense involving as many buttons, gold tassels, medals and feathers as can be crammed onto a uniform, Murat fought in approximately 200 battles and looked great doing it.

In her memoirs, Caroline Murat, daughter of Joachim’s second son Prince Napoleon Lucien Charles Murat, described her grandfather’s dashing style of dress and fearlessness in combat.

His form was tall, his tread like that of a king, his face strikingly noble, while his piercing glance few men could bear. He had heavy black whiskers and long black locks, which contrasted singularly with his fiery blue eyes. He usually wore a three-cornered hat, with a magnificent white plume of ostrich feathers. […]

My grandfather’s dazzling exterior made him a mark for the enemy’s bullets. The wonder is that, being so conspicuous, he was never shot down and was rarely wounded. At one battle a bullet grazed his cheek. Like lightning his sword punished the offender by carrying away two of his fingers. I have read that at the battle of Aboukir he charged with his cavalry straight through the Turkish ranks, driving column after column into the sea.

Murat’s ascent was too inextricably tied to Napoleon’s to survive his mentor’s fall. In the attempt to preserve his throne, he went so far as to enter into an alliance with Austria after France’s defeat at the Battle of Leipzig in October of 1813, but his Austrian allies turned out to be fair-weather friends at best, and when he realized they planned to remove him from the throne during the Hundred Days, he declared himself in favor of Italian independence and fought the Austrians in northern Italy. He was defeated and fled, first attempting to get his old job back but Napoleon wouldn’t even see him, a choice the emperor would come to regret bitterly. (On St. Helena he said: “at Waterloo Murat might have given us the victory. For what did we need? To break three or four English squares. Murat was just the man for the job.”) After Napoleon’s rejection, Murat went to Corsica and mustered up 250 or so men with whom he planned to reconquer the throne of Naples from the restored Bourbon king Ferdinand IV.

Murat’s ascent was too inextricably tied to Napoleon’s to survive his mentor’s fall. In the attempt to preserve his throne, he went so far as to enter into an alliance with Austria after France’s defeat at the Battle of Leipzig in October of 1813, but his Austrian allies turned out to be fair-weather friends at best, and when he realized they planned to remove him from the throne during the Hundred Days, he declared himself in favor of Italian independence and fought the Austrians in northern Italy. He was defeated and fled, first attempting to get his old job back but Napoleon wouldn’t even see him, a choice the emperor would come to regret bitterly. (On St. Helena he said: “at Waterloo Murat might have given us the victory. For what did we need? To break three or four English squares. Murat was just the man for the job.”) After Napoleon’s rejection, Murat went to Corsica and mustered up 250 or so men with whom he planned to reconquer the throne of Naples from the restored Bourbon king Ferdinand IV.

This was not a well conceived plan, needless to say. His three ships were scattered in a storm. The one carrying him and 26 men was blown off course and landed in the southern Italian town of Pizzo, Calabria, near the toe of the boot, where he was promptly captured by Bourbon forces. Napoleon noted dryly that “Murat has tried to reconquer with 200 men the territory he was unable to hold when he had 80,000 of them.” Ferdinand ordered a show trial — the judges were appointed on the same day the order for his execution was sent by telegraph — and on October 13th, 1815, Joachim Murat was convicted of insurrection and sentenced to death by firing squad.

He died how he lived — well dressed, vain and fearless. His last request was for a perfumed bath and the opportunity to write to his wife and children. He refused the offer of a stool to sit on and a blindfold and stood unblinking before the fusiliers, dressed to the nines and smelling terrific. The phrasing has come down in several versions, but his last words to his executioners were so epic people are still quoting them without realizing that they’re quoting anyone: “Soldiers, do your duty. Aim for my heart, but spare my face. Fire!”

He died how he lived — well dressed, vain and fearless. His last request was for a perfumed bath and the opportunity to write to his wife and children. He refused the offer of a stool to sit on and a blindfold and stood unblinking before the fusiliers, dressed to the nines and smelling terrific. The phrasing has come down in several versions, but his last words to his executioners were so epic people are still quoting them without realizing that they’re quoting anyone: “Soldiers, do your duty. Aim for my heart, but spare my face. Fire!”

His old friend and administrator of his duchy Jean-Michel Agar, the Count of Mosburg, eulogized him poetically: “He knew how to win. He knew how to rule. He knew how to die.” Napoleon’s final assessment was a tad harsher: “In battle he was perhaps the bravest man in the world; left to himself, he was an imbecile without judgment.”

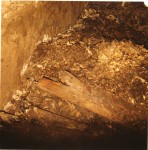

Murat’s remains are thought to have been interred in a mass grave underneath Pizzo’s Church of St. George, but there were rumors that they had been spirited away to France. There’s a memorial grave for Joachim Murat and his family in Paris’ Père Lachaise Cemetery. In 1899, his granddaughter Countess Letizia Rasponi Murat tried to find his remains in the St. George crypt so they could rebury them with dignity in the Certosa di Bologna cemetery. They were not successful. In 1976, the crypt was exposed during repairs to the church floor. Photographs were taken through a foot-wide hole in the trap door but all they captured was the basement full of bones and humus. Determining which parts belonged to Murat would seem a fool’s errand.

Murat’s remains are thought to have been interred in a mass grave underneath Pizzo’s Church of St. George, but there were rumors that they had been spirited away to France. There’s a memorial grave for Joachim Murat and his family in Paris’ Père Lachaise Cemetery. In 1899, his granddaughter Countess Letizia Rasponi Murat tried to find his remains in the St. George crypt so they could rebury them with dignity in the Certosa di Bologna cemetery. They were not successful. In 1976, the crypt was exposed during repairs to the church floor. Photographs were taken through a foot-wide hole in the trap door but all they captured was the basement full of bones and humus. Determining which parts belonged to Murat would seem a fool’s errand.

In April of 2007, Professor Pino Pagnotta, president of the Joachim Murat Association, got a hold of the pictures from the 70s and studied them closely. He had them enlarged and enhanced and was able to see more than 1976 photographic technology had allowed. He spied a broken casket made of a plain wood with a cord entwined in the boards. This matches contemporary eye-witness accounts like the one of Antonino Condoleo, a youth of 15 in 1815, who assisted in the burial of Joachim Murat. Condoleo describes a mishap on the way to the church when the plain fir casket containing Murat’s body was dropped and broken. They hastily tied the casket back together with a long cord and got it to St. George’s church where it was dumped unceremoniously in the crypt.

The discovery made news at the time and the Joachim Murat Association advocated strenuously that the remains in and/or around the broken coffin be DNA tested. Eight years later, they’ve finally gotten all the various authorities clerical and secular to sign on to the project. (I suspect Richard III was not far from their minds. Pizzo’s main tourist draw is the 15th century castle built by Frederick I of Aragon in which Murat was tried and executed. The castle was renamed after him and now receives thousands of visitors a year.)

The discovery made news at the time and the Joachim Murat Association advocated strenuously that the remains in and/or around the broken coffin be DNA tested. Eight years later, they’ve finally gotten all the various authorities clerical and secular to sign on to the project. (I suspect Richard III was not far from their minds. Pizzo’s main tourist draw is the 15th century castle built by Frederick I of Aragon in which Murat was tried and executed. The castle was renamed after him and now receives thousands of visitors a year.)

In May, the heavy marble slab sealing the basement will be moved and biologist Sergio Romano will be lowered into the crypt where he will take pictures and samples from the broken casket. If DNA can be extracted from the samples — a very big if — it can be tested against Murat’s many descendants, among then his three times great-grandson actor René Auberjonois, aka the shapeshifter Odo in Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, whose late mother was Princess Laure Louise Napoléone Eugénie Caroline Murat.