When the rediscovery of Salvator Mundi, Leonardo da Vinci’s painting of Christ as the Savior of the Word, exploded onto the world stage in June of 2011, details about who owned the painting and their future plans for the work after its exhibition at the London’s National Gallery blockbuster exhibition Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan were not forthcoming. It was revealed by art trade insiders last year that the masterpiece had been privately sold by the consortium of art dealers to, whom else, an anonymous private collector in May 2013 for between $75 million and $80 million. Sotheby’s brokered the sale and of course they never kiss and tell, nor did Robert Simon, one of the few known members of the consortium, when the New York Times asked him about it.

When the rediscovery of Salvator Mundi, Leonardo da Vinci’s painting of Christ as the Savior of the Word, exploded onto the world stage in June of 2011, details about who owned the painting and their future plans for the work after its exhibition at the London’s National Gallery blockbuster exhibition Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan were not forthcoming. It was revealed by art trade insiders last year that the masterpiece had been privately sold by the consortium of art dealers to, whom else, an anonymous private collector in May 2013 for between $75 million and $80 million. Sotheby’s brokered the sale and of course they never kiss and tell, nor did Robert Simon, one of the few known members of the consortium, when the New York Times asked him about it.

That little item in the Times’ ArtsBeat blog had quite the unintended consequence when the anonymous private collector in question found out that the painting he’d bought for $127.5 million was sold for $50 million less that, and that wasn’t the only artwork for which he’d paid through several noses. Irked by these revelations, the collector took it to the authorities and now all that precious secrecy that the art and antiquities trade loves so much has blown up in everyone’s faces.

The owner of the Salvator Mundi is Russian potash billionaire Dmitry Rybolovlev, or technically the trust he’s created to shelter the vast art collection worth an estimated $2 billion he’s amassed over the past decade. More than 40 of these works — including important pieces by Picasso, Toulouse-Lautrec, Modigliani, Magritte, Gauguin, Degas and Rothko along with the Leonardo — he acquired through his preferred art dealer, Swiss businessman Yves Bouvier who first got into art dealing by owning tax-free warehouses in the same shady freeports that so prominently feature in the looted antiquities trade. When he saw the kind of insane amounts of money changing hands, he figured out he could make the big bucks trading in the contents of the warehouses, not just the rental of the space.

The owner of the Salvator Mundi is Russian potash billionaire Dmitry Rybolovlev, or technically the trust he’s created to shelter the vast art collection worth an estimated $2 billion he’s amassed over the past decade. More than 40 of these works — including important pieces by Picasso, Toulouse-Lautrec, Modigliani, Magritte, Gauguin, Degas and Rothko along with the Leonardo — he acquired through his preferred art dealer, Swiss businessman Yves Bouvier who first got into art dealing by owning tax-free warehouses in the same shady freeports that so prominently feature in the looted antiquities trade. When he saw the kind of insane amounts of money changing hands, he figured out he could make the big bucks trading in the contents of the warehouses, not just the rental of the space.

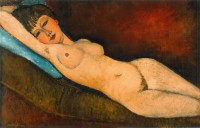

Their lucrative business relationship came to a screeching halt when Rybolovlev found out at a party last New Year’s Eve that the Modigliani painting Nu Couché au Coussin Bleu he had purchased for $118 million was sold by its previous owner for $93 million. Even for the billionaire luxury goods market, a $25 million mark-up is bold. That proved to be modest by comparison to the mark-up on the Leonardo. Rybolovlev already paid Bouvier a commission of two percent on every sale — he was presented with two separate invoices each time, one for the cost of the artwork, one for two percent of its value — so he was less than pleased to find a whole other level of commission hidden in the price of the paintings.

Their lucrative business relationship came to a screeching halt when Rybolovlev found out at a party last New Year’s Eve that the Modigliani painting Nu Couché au Coussin Bleu he had purchased for $118 million was sold by its previous owner for $93 million. Even for the billionaire luxury goods market, a $25 million mark-up is bold. That proved to be modest by comparison to the mark-up on the Leonardo. Rybolovlev already paid Bouvier a commission of two percent on every sale — he was presented with two separate invoices each time, one for the cost of the artwork, one for two percent of its value — so he was less than pleased to find a whole other level of commission hidden in the price of the paintings.

Nine days after the New Year’s Eve party, Rybolovlev filed a criminal complaint against Bouvier in Monaco for document forgery (the invoices) and fraud (the inflated price of the art). In Monaco individuals and companies can file criminal complaints that the police and prosecutors will investigate without alerting the potential defendant. Apparently the investigation in this case bore fruit and on February 25th, Rybolovlev invited Bouvier over to his office in Monaco ostensibly to discuss payment of Rothko’s N° 6 – Violet, Green and Red he’d purchased for $140 million last year. The dealer was greeted at the door by eight cops who arrested him on charges of document forgery and fraud.

He was detained for three days until he could rustle up 10 million euros in bail money, which apparently took some time to raise despite his wallowing in filthy lucre because said lucre isn’t in fluid cash. Meanwhile, Rybolovlev’s legal team also got Singapore, where Bouvier owns freeports, to freeze $500 million of his company’s assets. Prosecutors in Geneva searcherd Bouvier’s company’s headquarters for documents related to the sales of the Modigliani nude and Salvator Mundi.

He was detained for three days until he could rustle up 10 million euros in bail money, which apparently took some time to raise despite his wallowing in filthy lucre because said lucre isn’t in fluid cash. Meanwhile, Rybolovlev’s legal team also got Singapore, where Bouvier owns freeports, to freeze $500 million of his company’s assets. Prosecutors in Geneva searcherd Bouvier’s company’s headquarters for documents related to the sales of the Modigliani nude and Salvator Mundi.

Bouvier insists he’s innocent, that he is not a broker but a seller. He bought those works from the owners fair and square and then resold them to Rybolovlev. That makes the tens of millions he made on top of the original sale price perfectly legitimate resale margin, “administrative costs,” not fraudulent hidden commissions. He says that the Russian oligarch is just using the courts to get out of paying the tens of millions he still owes on that Rothko. He claims that Rybolovlev laid the trap to have him arrested because he wanted to put him “in the gulag” and let him stew there, to intimidate him into giving up his claim to the as-yet unpaid Rothko moneys.

Rybolovlev responds that as per their agreement, he is paying off the Rothko in stages and the payments are still on schedule so there are no millions outstanding. His complaint presents evidence refuting Bouvier’s claim to be a reseller rather than a broker, namely letters in which Bouvier discusses negotiating terms of sale with owners on Rybolovlev’s behalf and insists on the importance of secrecy because if word gets out that the owner wants to sell, then they run the risk of “losing it to auction.” Or of Rybolovlev finding out that Bouvier was pocketing tens of millions in the transaction.

So the bad news is that one of fewer than 20 known surviving Leonardo da Vinci paintings is squirreled away in wherever Rybolovlev hoards his preciouses. The good news is that the we get to watch all of this play out in the light of day for a change.