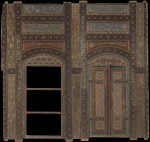

In late Ottoman-era Damascus, the wealthy had homes built in the Old City that looked plain on the outside but only because they were saving all the good stuff for the interiors. Richly decorated rooms with elaborately carved and painted wood panels and colorful stone inlays faced onto courtyards kept cool and fragrant by fountains and fruit trees. The rooms were designed to welcome and impress important visitors with luxurious comfort. They would enter the home through a modest door and walk down an unassuming hallway before turning the corner onto a courtyard surrounded by living spaces often on two stories. The more expensive the home, the more courtyards it had.

In late Ottoman-era Damascus, the wealthy had homes built in the Old City that looked plain on the outside but only because they were saving all the good stuff for the interiors. Richly decorated rooms with elaborately carved and painted wood panels and colorful stone inlays faced onto courtyards kept cool and fragrant by fountains and fruit trees. The rooms were designed to welcome and impress important visitors with luxurious comfort. They would enter the home through a modest door and walk down an unassuming hallway before turning the corner onto a courtyard surrounded by living spaces often on two stories. The more expensive the home, the more courtyards it had.

There were 17,000 of these 18th and 19th century courtyard homes still standing in Damascus in 1900, but the clock was ticking. The great beauty of the rooms made them worth more than the homes when they were stripped and sold to museums and collectors overseas. Doris Duke bought two of them and installed them in her Honolulu home Shangri La, now the Shangri La Center for Islamic Arts and Cultures. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City scored their Damascus Room in 1970.

There were 17,000 of these 18th and 19th century courtyard homes still standing in Damascus in 1900, but the clock was ticking. The great beauty of the rooms made them worth more than the homes when they were stripped and sold to museums and collectors overseas. Doris Duke bought two of them and installed them in her Honolulu home Shangri La, now the Shangri La Center for Islamic Arts and Cultures. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City scored their Damascus Room in 1970.

Most of the late Ottoman homes were demolished in the late 1970s when a building boom laid waste to the Old City. One of the casualties of the boom was a courtyard house built around 1766 that was demolished during the construction of a road in the al-Bahsa quarter. Before it was destroyed in 1978, a Lebanese art dealer bought the home’s 15 by 20-foot reception room, known as the qa’a. The decorated wood panels on the walls, the inlaid stone floor, an inlaid limestone and marble wall fountain, everything that was nailed down was unnailed and moved to Beirut where it was stored in a warehouse for thirty years.

Most of the late Ottoman homes were demolished in the late 1970s when a building boom laid waste to the Old City. One of the casualties of the boom was a courtyard house built around 1766 that was demolished during the construction of a road in the al-Bahsa quarter. Before it was destroyed in 1978, a Lebanese art dealer bought the home’s 15 by 20-foot reception room, known as the qa’a. The decorated wood panels on the walls, the inlaid stone floor, an inlaid limestone and marble wall fountain, everything that was nailed down was unnailed and moved to Beirut where it was stored in a warehouse for thirty years.

After somehow surviving more than three decades in a war zone, the dismantled room caught the eye of Linda Komaroff, head of the Middle Eastern art department at the L.A. County Museum of Art (LACMA). In 2011 she saw pictures of it and by the end of the year she was actively lobbying the museum to acquire the room. As the conflict in Syria took an increasingly monstrous toll on the country’s cultural heritage, Komaroff’s advocacy took on additional urgency. Finally in spring of 2014, the purchase was finalized and LACMA became the proud owner of an 18th century Damascus Room of its own.

After somehow surviving more than three decades in a war zone, the dismantled room caught the eye of Linda Komaroff, head of the Middle Eastern art department at the L.A. County Museum of Art (LACMA). In 2011 she saw pictures of it and by the end of the year she was actively lobbying the museum to acquire the room. As the conflict in Syria took an increasingly monstrous toll on the country’s cultural heritage, Komaroff’s advocacy took on additional urgency. Finally in spring of 2014, the purchase was finalized and LACMA became the proud owner of an 18th century Damascus Room of its own.

The room is in excellent condition. Only one important part of it — the ceiling — is missing, likely due to water intrusion since the wall panels have visible water damage up top where they would have once joined the ceiling. Unlike most of its compatriots, this room was never renovated, altered or painted over so the original surfaces are still brilliant and saturated underneath a few layers of grime.

As is typical, it has multicolored inlaid stone floors, painted wood walls, elaborate cupboard doors and storage niches, a spectacular arch with plaster voussoirs decorated with colored inlays that served to divide the room into upper and lower sections separated by a single tall step; and an intricately inlaid stone wall fountain with a carved and painted hood. Perhaps because the room remained in storage for so many years and had never been reinstalled or restored, it is largely in its original, though aged, state, with one of the best-preserved painted surfaces—including bright pinks, oranges, blues, and greens—of any similar room of the period. The decoration, mainly floral, incorporates on the cornices detailed depictions of platters of fruit, nuts, and even baklava, which must have served to whet the appetites of visitors to the room as they awaited the same types of refreshment.

The poplar wood panels were decorated using a technique called ‘ajami in which a thick layer of gypsum and glue was applied to the wood and carved in relief before being painted and accented with tin leaf which itself would be painted with colored glazes. Gold leaf accents added shine while egg tempera paints produced contrasting matte surfaces. Because LACMA’s room has managed to avoid the fate of so many others of its kind and has such a well preserved original surface, researchers expert to learn more about the ‘ajami technique and materials used by examining it.

The poplar wood panels were decorated using a technique called ‘ajami in which a thick layer of gypsum and glue was applied to the wood and carved in relief before being painted and accented with tin leaf which itself would be painted with colored glazes. Gold leaf accents added shine while egg tempera paints produced contrasting matte surfaces. Because LACMA’s room has managed to avoid the fate of so many others of its kind and has such a well preserved original surface, researchers expert to learn more about the ‘ajami technique and materials used by examining it.

Cleaning and conservation on the room has begun, funded in large part by the King Abdulaziz Center for World Culture in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia. The stone only needs cleaning; it’s the wood panels that need to be cleaned, repaired and stabilized for permanent display. The LACMA team is also taking an innovative approach by building an armature for the room so that it can be moved whole to different exhibition spaces.

Cleaning and conservation on the room has begun, funded in large part by the King Abdulaziz Center for World Culture in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia. The stone only needs cleaning; it’s the wood panels that need to be cleaned, repaired and stabilized for permanent display. The LACMA team is also taking an innovative approach by building an armature for the room so that it can be moved whole to different exhibition spaces.

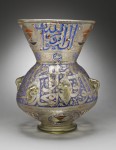

This will be immediately relevant because the renovated room will first go on display in Dhahran at the inaugural exhibition of the King Abdulaziz Center for World Culture in March of next year. Accompanied by 130 of the best pieces from LACMA’s extensive Islamic Art collection, the room will be in Saudi Arabia for two years before returning to Los Angeles. That gives LACMA a breather because they have no idea where to put this room. The problem is they need ceilings 20 feet high and LACMA’s current building doesn’t have any of those. There’s a new building in the works, but construction isn’t even scheduled to begin until 2018.

This will be immediately relevant because the renovated room will first go on display in Dhahran at the inaugural exhibition of the King Abdulaziz Center for World Culture in March of next year. Accompanied by 130 of the best pieces from LACMA’s extensive Islamic Art collection, the room will be in Saudi Arabia for two years before returning to Los Angeles. That gives LACMA a breather because they have no idea where to put this room. The problem is they need ceilings 20 feet high and LACMA’s current building doesn’t have any of those. There’s a new building in the works, but construction isn’t even scheduled to begin until 2018.