Construction workers building a new apartment complex in Tallinn, the capital of Estonia, have discovered the remains of two medieval ships. Workers were digging the foundations on May 22nd when the bucket of the excavator encountered large pieces of very old wood. The construction company stopped work and alerted the National Heritage Board (NHB) who sent experts to examine the find. On May 26th the crew unearthed another shipwreck at the other end of the construction site. The area was then scanned with ground-penetrating radar and a third likely shipwreck was located.

Construction workers building a new apartment complex in Tallinn, the capital of Estonia, have discovered the remains of two medieval ships. Workers were digging the foundations on May 22nd when the bucket of the excavator encountered large pieces of very old wood. The construction company stopped work and alerted the National Heritage Board (NHB) who sent experts to examine the find. On May 26th the crew unearthed another shipwreck at the other end of the construction site. The area was then scanned with ground-penetrating radar and a third likely shipwreck was located.

Construction has been suspended and this week NHB archaeologists began excavating the first shipwreck. The bones of the ship are now clearly visible and can be seen by members of the public who care to glance down. It’s 15 meters (50 feet) long, four meters (13 feet) wide and 1.5 meters (five feet) deep at the deepest point. Archaeologists tentatively date it to between the 14th to 17th century.

Construction has been suspended and this week NHB archaeologists began excavating the first shipwreck. The bones of the ship are now clearly visible and can be seen by members of the public who care to glance down. It’s 15 meters (50 feet) long, four meters (13 feet) wide and 1.5 meters (five feet) deep at the deepest point. Archaeologists tentatively date it to between the 14th to 17th century.

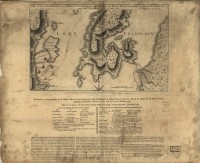

It was found close to four meters below modern ground level, in the sediments of what was once the seabed. Although the site is 200 meters (ca. 220 yards) from the water today, for centuries it was a port. In the late 1930s the area was infilled with ash and household refuse. It’s not clear if the ships sank there are were gradually buried over time by siltification, or if they were deliberately sunk after reaching the end of their natural lives. They were certainly stripped of all usable parts — metal fittings, rigging and masts — before being abandoned.

It was found close to four meters below modern ground level, in the sediments of what was once the seabed. Although the site is 200 meters (ca. 220 yards) from the water today, for centuries it was a port. In the late 1930s the area was infilled with ash and household refuse. It’s not clear if the ships sank there are were gradually buried over time by siltification, or if they were deliberately sunk after reaching the end of their natural lives. They were certainly stripped of all usable parts — metal fittings, rigging and masts — before being abandoned.

Estonian Maritime Museum archeologist Vello Mässi believes it was a short-haul transport vessel, used to move cargo from the shore to the large ships in the deeper waters of the bay. Archaeologists are excited to have the opportunity to study such old ships in detail. This is the first time multiple historic wrecks have been found so close together. The last time the remains of a wreck were found in Tallinn was 2009 when road construction unearthed a 13th century ship. They are keen to examine these finds to learn about how they were built and when and what wood was used.

Estonian Maritime Museum archeologist Vello Mässi believes it was a short-haul transport vessel, used to move cargo from the shore to the large ships in the deeper waters of the bay. Archaeologists are excited to have the opportunity to study such old ships in detail. This is the first time multiple historic wrecks have been found so close together. The last time the remains of a wreck were found in Tallinn was 2009 when road construction unearthed a 13th century ship. They are keen to examine these finds to learn about how they were built and when and what wood was used.

Archaeologist Priit Lahi admits the find was an important discovery to shed light on possible shipbuilding methods from centuries before.

“At the time, shipbuilders used their own methods — it wasn’t very scientific. There weren’t project drawings like we have today,” he told the Associated Press.

Excavations are scheduled to continue at least through July 8th. While the developers building the apartment complex have expressed interest in display the find in some way, construction won’t be delayed much longer or halted. It would be too expensive and time-consuming to keep the wrecks in situ, so they will be raised, documented and studied before their ultimate disposition is decided. They may be reburied in sand at another location for their own preservation, which would allow future examination of the wrecks by scholars and make them easy to retrieve for future conservation and display.

Excavations are scheduled to continue at least through July 8th. While the developers building the apartment complex have expressed interest in display the find in some way, construction won’t be delayed much longer or halted. It would be too expensive and time-consuming to keep the wrecks in situ, so they will be raised, documented and studied before their ultimate disposition is decided. They may be reburied in sand at another location for their own preservation, which would allow future examination of the wrecks by scholars and make them easy to retrieve for future conservation and display.

For more pictures of the ship and site, check out the photo galleries here and here.