Archaeologists from the La Corona Regional Archaeological Project have discovered Mayan hieroglyphic stone panels (pdf) at the archaeological sites of La Corona and El Achiotal in Western Petén, Guatemala, that lend new insight into important periods of Mayan history.

Archaeologists from the La Corona Regional Archaeological Project have discovered Mayan hieroglyphic stone panels (pdf) at the archaeological sites of La Corona and El Achiotal in Western Petén, Guatemala, that lend new insight into important periods of Mayan history.

La Corona was occupied in the Maya Classic period (Classic period (c. 250–900 A.D.) while El Achiotal, a smaller site 12 miles east of La Corona, was occupied earlier, in the Late Preclassic and Early Classic between 400 B.C. and 550 A.D. Both sites, which are about 12 miles away from each other in the dense Petén jungle, have been heavily preyed upon by looters who left deep trenches and tunnels in almost all of the buildings, but archaeologists have only recently reached the remote area. For 40 years it was known from the plethora of looted stone panels in museums, galleries and collections all over the world as the mysterious Site Q. Mayanist Ian Graham and University of Texas at Austin epigrapher David Stuart finally found Site Q in 1997 and named it La Corona after its ring of five temples that resemble a crown. The discovery of a hieroglyphic stone panel in 2005 that was made of identical stone and had identical content to Site Q monuments confirmed La Corona’s identity.

That discovery led to the creation of the La Corona Regional Archaeological Project, co-directed by Marcello Canuto of Tulane University (discover of the 2005 panel) and Tomás Barrientos of the Universidad del Valle de Guatemala, in 2008. Its aim was to recontextualize the looted artifacts, Since then, the Project has been excavating La Corona and environs, establishing a permanent camp, involving residents in creating a long-term plan to protect this center of ancient lowland Maya civilization from looters, poachers and illegal settlers who burn the jungle to make pasture land for cattle. Despite the destruction wrought by looters, archaeologists have made momentous discoveries, including a hieroglyphic staircase in 2012 that documented 200 years of Maya history and referred to the December 21st date that made so many people freak out about the so-called Mayan apocalypse that year.

That discovery led to the creation of the La Corona Regional Archaeological Project, co-directed by Marcello Canuto of Tulane University (discover of the 2005 panel) and Tomás Barrientos of the Universidad del Valle de Guatemala, in 2008. Its aim was to recontextualize the looted artifacts, Since then, the Project has been excavating La Corona and environs, establishing a permanent camp, involving residents in creating a long-term plan to protect this center of ancient lowland Maya civilization from looters, poachers and illegal settlers who burn the jungle to make pasture land for cattle. Despite the destruction wrought by looters, archaeologists have made momentous discoveries, including a hieroglyphic staircase in 2012 that documented 200 years of Maya history and referred to the December 21st date that made so many people freak out about the so-called Mayan apocalypse that year.

What the excavations have found is that La Corona, a very small city compared to the great Mayan powers like Calakmul and Tikal, had a disproportionately high number and quality of stone inscriptions. Like El Perú-Waka’, La Corona was a key city on the essential trade route from Calakmul (in modern-day Mexico) through the Mayan lowlands to its southern allies. It therefore had close ties to Calakmul — generations of Calakmul Snake dynasty princesses married lords of La Corona — access to the best scribes and artisans, and, coincidentally, a rich source of limestone all of which combined to give rise to a unique carving tradition. While the inscriptions found at other small Mayan cities tend to focus on local history and rulers, La Corona’s also detail the history of people and places far outside of its boundaries, including important city-states that are not mentioned anywhere else in the epigraphic record.

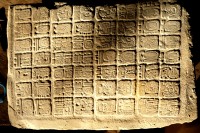

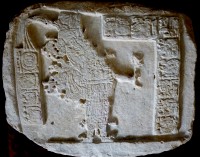

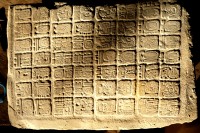

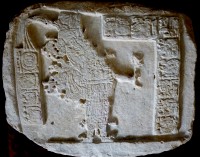

The newly discovered panels fit neatly into this tradition. They are extremely high quality carvings and describe people and events described nowhere else. In La Corona, two stele in excellent condition were found embedded in a wall in the palace on the main plaza. They had originally been installed elsewhere in the city, possibly a temple, and were later reset in a masonry bench near the northeast corner of the palace. One, depicting a Calakmul king mid-dance, dates to 702 A.D. The other is a grid of glyphics from the late 7th century that describes the deeds of a ruler of La Corona named Chak Ak’ Paat Yuk.

The newly discovered panels fit neatly into this tradition. They are extremely high quality carvings and describe people and events described nowhere else. In La Corona, two stele in excellent condition were found embedded in a wall in the palace on the main plaza. They had originally been installed elsewhere in the city, possibly a temple, and were later reset in a masonry bench near the northeast corner of the palace. One, depicting a Calakmul king mid-dance, dates to 702 A.D. The other is a grid of glyphics from the late 7th century that describes the deeds of a ruler of La Corona named Chak Ak’ Paat Yuk.

The panel inscriptions tell fascinating stories of rituals of kingly accession that involve travel, costuming, dancing, invocation of gods and reverence of ancestors. Stuart, who also deciphered the panels, states: “The gorgeous hieroglyphs give us new insights about the ceremonies that led up to a new king being crowned. And they fill important gaps we had in La Corona’s rich history.”

David Stuart has written a fascinating blog entry about the glyphs on the La Corona panels here.

At El Achiotal, researchers found two pieces of a 5th century stela placed in a shrine in a building in the central plaza. They had also been moved in antiquity from their original site to the enclosed shrine. The panel was already broken when the pieces were installed in the shrine and El Achiotal residents left offerings to it for generations, underscoring its cultural importance. Although broken, the carving and stone are in such good condition that much of the original red paint is intact.

At El Achiotal, researchers found two pieces of a 5th century stela placed in a shrine in a building in the central plaza. They had also been moved in antiquity from their original site to the enclosed shrine. The panel was already broken when the pieces were installed in the shrine and El Achiotal residents left offerings to it for generations, underscoring its cultural importance. Although broken, the carving and stone are in such good condition that much of the original red paint is intact.

Expert epigrapher David Stuart of the University of Texas at Austin estimated the stela’s date to be November 22, A.D. 418. “This was a time of great political upheaval in the central Maya area, when a Teotihuacan warrior-ruler named Siyaj K’ahk’ arrived in A.D. 378 and set up a new political order centered at Tikal. It seems that the Achiotal king came to power shortly after that time” says Stuart.

Expert epigrapher David Stuart of the University of Texas at Austin estimated the stela’s date to be November 22, A.D. 418. “This was a time of great political upheaval in the central Maya area, when a Teotihuacan warrior-ruler named Siyaj K’ahk’ arrived in A.D. 378 and set up a new political order centered at Tikal. It seems that the Achiotal king came to power shortly after that time” says Stuart.

So, besides individual accolades, this stela places the long reign and accomplishments of El Achiotal’s king into a larger historical framework. “Based on parallels known from other sites, we think that this stela relates to this watershed event in Maya history — the installation, in the Maya lowlands, of a foreign power that can ultimately be traced to Teotihuacan. Indeed, although details of this event remain murky, this stela provides another piece of the Maya historical puzzle,” says Canuto.

So, besides individual accolades, this stela places the long reign and accomplishments of El Achiotal’s king into a larger historical framework. “Based on parallels known from other sites, we think that this stela relates to this watershed event in Maya history — the installation, in the Maya lowlands, of a foreign power that can ultimately be traced to Teotihuacan. Indeed, although details of this event remain murky, this stela provides another piece of the Maya historical puzzle,” says Canuto.

Researchers have found the earliest known evidence of dentistry in the molar of a Palaeolithic man who lived between 13,820 and 14,160 years ago. The young man, who was around 25 years old at the time of death, had a cavity removed with a sharp flint, beating the dental work previously thought to be the oldest (a molar found in a Neolithic graveyard in Pakistan that was perforated by a bow drill) by 5,000 years.

Researchers have found the earliest known evidence of dentistry in the molar of a Palaeolithic man who lived between 13,820 and 14,160 years ago. The young man, who was around 25 years old at the time of death, had a cavity removed with a sharp flint, beating the dental work previously thought to be the oldest (a molar found in a Neolithic graveyard in Pakistan that was perforated by a bow drill) by 5,000 years.  The skeleton was found in the Ripari Villabruna rock shelter in the Dolomite mountains of northern Italy in 1988. The skeletal remains had been laid to rest in a shallow grave along with what were probably the hunter’s most prized possessions: a flint knife, a hammer stone, a flint blade and a piece of sharpened bone. Stones decorated with red ochre marked the burial mound. The bones were in usually good condition and a large cavity in his lower right third molar was noticed at the time, but the attempted treatment was not visible to the naked eye. It was only when researchers recently examined the molar with a scanning electron microscope (SEM) that they realized the cavity was signficantly larger than the decayed tissue and that there were striations and chips on the walls of the cavity even in the most inaccessible parts of the tooth.

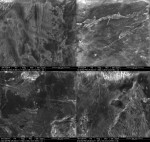

The skeleton was found in the Ripari Villabruna rock shelter in the Dolomite mountains of northern Italy in 1988. The skeletal remains had been laid to rest in a shallow grave along with what were probably the hunter’s most prized possessions: a flint knife, a hammer stone, a flint blade and a piece of sharpened bone. Stones decorated with red ochre marked the burial mound. The bones were in usually good condition and a large cavity in his lower right third molar was noticed at the time, but the attempted treatment was not visible to the naked eye. It was only when researchers recently examined the molar with a scanning electron microscope (SEM) that they realized the cavity was signficantly larger than the decayed tissue and that there were striations and chips on the walls of the cavity even in the most inaccessible parts of the tooth.  The striations look like tiny versions of cut marks on bone. The research team experimented with sharpened wood, bone and flint points on the enamel of three molars and confirmed that the striations and enamel chipping on the cavity walls were made before death by pointed stone tool scratching and digging into the lesion. That means someone took a very small, very sharp tool, probably a flint, and dug out as much of the decay as they could. The striations go on in all different directions so the cavedentist really got down in there, changing angles and positions to clean out the rotted parts. The pain and difficulty of this procedure suggests that the dangers of tooth decay were known in the Late Upper Palaeolithic.

The striations look like tiny versions of cut marks on bone. The research team experimented with sharpened wood, bone and flint points on the enamel of three molars and confirmed that the striations and enamel chipping on the cavity walls were made before death by pointed stone tool scratching and digging into the lesion. That means someone took a very small, very sharp tool, probably a flint, and dug out as much of the decay as they could. The striations go on in all different directions so the cavedentist really got down in there, changing angles and positions to clean out the rotted parts. The pain and difficulty of this procedure suggests that the dangers of tooth decay were known in the Late Upper Palaeolithic.