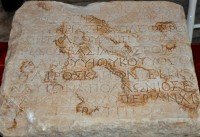

Archaeologists excavating the Roman site of Aquae Calidae in Burgas on the Bulgarian Black Sea coast discovered a marble slab with an inscription mentioning the last monarchs of the Sapaean dynasty, the last family to rule the ancient Odrysian kingdom of Thrace. The Greek inscription was carved between 26 and 37 A.D., a decade or two before Thrace ceased being a Roman client state in 46 A.D. and was absorbed into the Roman Empire as the province of Thracia.

Archaeologists excavating the Roman site of Aquae Calidae in Burgas on the Bulgarian Black Sea coast discovered a marble slab with an inscription mentioning the last monarchs of the Sapaean dynasty, the last family to rule the ancient Odrysian kingdom of Thrace. The Greek inscription was carved between 26 and 37 A.D., a decade or two before Thrace ceased being a Roman client state in 46 A.D. and was absorbed into the Roman Empire as the province of Thracia.

The inscribed marble appears to be a dedication. It refers to a sanctuary to Demeter built by Apollonius Eptaikentus, strategos (military governor) of the city and region of region under the Sapaean King Rhoemetalces II. The slab was in all likelihood part of the sanctuary complex and archaeologists hope remains of it may still be found in Aquae Calidae, only 10% of which has been excavated.

The inscription lists the names of the last three kings of Odrysian Thrace and their dynastic connections. It is the first source to note the names of the children of Rhoemetalces II (r. 18-38 A.D.) and his sister Pythodoris II (r. 38–46 A.D.). It also confirms a previously uncertain familial link: that Pythodoris II was the daughter of King Cotys III (r. 12-18 A.D.), the son of Rhoemetalces I (r. 12 B.C. – 12 A.D.). Cotys III was killed by his uncle Rhescuporis II, so that means Pythodoris II, who married her cousin Rhoemetalces III, was wedded to the son of her father’s assassin. Surprising no one, she had her husband killed in 46 A.D. We don’t know what happened to her, but Rome took swift advantage of the power vacuum after Rhoemetalces III’s death and secured itself a new province.

This is important information about people for whom we have mainly numismatic evidence. The ancient sources are a bit thin on this time period, although Tacitus goes into some detail in Book Two of The Annals on how Augustus and Tiberius divided and conquered Thrace after the death of Rhoemetalces I. Pardon the long blockquote, but it’s such a delicious taste of the devious machinations of empire-building that I can’t resist including the whole story.

Tiberius … planned a crafty scheme against Rhescuporis, king of Thrace. That entire country had been in the possession of Rhoemetalces, after whose death Augustus assigned half to the king’s brother Rhescuporis, half to his son Cotys. In this division the cultivated lands, the towns, and what bordered on Greek territories, fell to Cotys; the wild and barbarous portion, with enemies on its frontier, to Rhescuporis. The kings too themselves differed, Cotys having a gentle and kindly temper, the other a fierce and ambitious spirit, which could not brook a partner. Still at first they lived in a hollow friendship, but soon Rhescuporis overstepped his bounds and appropriated to himself what had been given to Cotys, using force when he was resisted, though somewhat timidly under Augustus, who having created both kingdoms would, he feared, avenge any contempt of his arrangement. When however he heard of the change of emperor, he let loose bands of freebooters and razed the fortresses, as a provocation to war.

Nothing made Tiberius so uneasy as an apprehension of the disturbance of any settlement. He commissioned a centurion to tell the kings not to decide their dispute by arms. Cotys at once dismissed the forces which he had prepared. Rhescuporis, with assumed modesty, asked for a place of meeting where, he said, they might settle their differences by an interview. There was little hesitation in fixing on a time, a place, finally on terms, as every point was mutually conceded and accepted, by the one out of good nature, by the other with a treacherous intent. Rhescuporis, to ratify the treaty, as he said, further proposed a banquet; and when their mirth had been prolonged far into the night, and Cotys amid the feasting and the wine was unsuspicious of danger, he loaded him with chains, though he appealed, on perceiving the perfidy, to the sacred character of a king, to the gods of their common house, and to the hospitable board. Having possessed himself of all Thrace, he wrote word to Tiberius that a plot had been formed against him, and that he had forestalled the plotter. Meanwhile, under pretext of a war against the Bastarnian and Scythian tribes, he was strengthening himself with fresh forces of infantry and cavalry.

He received a conciliatory answer. If there was no treachery in his conduct, he could rely on his innocence, but neither the emperor nor the Senate would decide on the right or wrong of his cause without hearing it. He was therefore to surrender Cotys, come in person and transfer from himself the odium of the charge.

This letter Latinius Pandus, proprietor of Moesia, sent to Thrace, with soldiers to whose custody Cotys was to be delivered. Rhescuporis, hesitating between fear and rage, preferred to be charged with an accomplished rather than with an attempted crime. He ordered Cotys to be murdered and falsely represented his death as self-inflicted. Still the emperor did not change the policy which he had once for all adopted. On the death of Pandus, whom Rhescuporis accused of being his personal enemy, he appointed to the government of Moesia Pomponius Flaccus, a veteran soldier, specially because of his close intimacy with the king and his consequent ability to entrap him.

Flaccus on arriving in Thrace induced the king by great promises, though he hesitated and thought of his guilty deeds, to enter the Roman lines. He then surrounded him with a strong force under pretence of showing him honour, and the tribunes and centurions, by counsel, by persuasion, and by a more undisguised captivity the further he went, brought him, aware at last of his desperate plight, to Rome. He was accused before the Senate by the wife of Cotys, and was condemned to be kept a prisoner far away from his kingdom. Thrace was divided between his son Rhœmetalces, who, it was proved, had opposed his father’s designs, and the sons of Cotys. As these were still minors, Trebellienus Rufus, an ex-praetor, was appointed to govern the kingdom in the meanwhile, after the precedent of our ancestors who sent Marcus Lepidus into Egypt as guardian to Ptolemy’s children. Rhescuporis was removed to Alexandria, and there attempting or falsely charged with attempting escape, was put to death.

I love Tacitus’ scepticism of his sources. He’s totally on my “who would you invite to dinner” fantasy list.

Aquae Calidae, a sanctuary and spa resort in the 1st century (its name means hot waters), has been excavated for the past six years. The digs have been funded by the city of Burgas as part of the construction of new sewage and water systems for the neighboring districts and so that the Aquae Calidae site can be partially restored it to make it an attractive destination for cultural heritage tourism. The discovery of the inscription will likely spur additional excavations in the attempt to find the sanctuary of Demeter as well as other remains, like an early Christian church, artifacts suggest may still be slumbering under the surface.