Childeric I was the king of the Salian Franks from 457 until his death in 481/2 A.D., and the father of Clovis I, the man who would unite the Frankish tribes under his rulership and become the first of the Merovingian kings of France. Childeric established a capital at Tournai on lands he had received as a foederatus (a military ally who received money and lands in exchange for fighting for Rome) in what was then the province of Belgica Secunda.

Clovis moved the capital to Paris and over time the location of his father’s tomb was lost. It was rediscovered on May 27th, 1653, by one Adrien Quinquin who was doing some work on the church of Saint-Brice when his shovel suddenly turned up a cache of gold coins. Further excavation revealed a tomb full of treasures, among them a throwing axe, a spear, a long sword called a spatha and a short scramasax with scabbard, both richly ornamented with gold and garnet cloisonné, a solid gold torc bracelet, part of an iron horseshoe with nails still in it, belt and shoe buckles and horse harness fittings also decorated in cloisonné gold and garnets, a leather purse containing more than a hundred gold and silver coins, the most recent bearing the image of the Byzantine Emperor Zeno (474-491 A.D.), a gold bull’s head with a solar disc on its forehead, a crystal ball and a gold signet ring.

Clovis moved the capital to Paris and over time the location of his father’s tomb was lost. It was rediscovered on May 27th, 1653, by one Adrien Quinquin who was doing some work on the church of Saint-Brice when his shovel suddenly turned up a cache of gold coins. Further excavation revealed a tomb full of treasures, among them a throwing axe, a spear, a long sword called a spatha and a short scramasax with scabbard, both richly ornamented with gold and garnet cloisonné, a solid gold torc bracelet, part of an iron horseshoe with nails still in it, belt and shoe buckles and horse harness fittings also decorated in cloisonné gold and garnets, a leather purse containing more than a hundred gold and silver coins, the most recent bearing the image of the Byzantine Emperor Zeno (474-491 A.D.), a gold bull’s head with a solar disc on its forehead, a crystal ball and a gold signet ring.

The signet ring was the proverbial smoking gun that identified the tomb as Childeric’s. It’s a heavy gold ring 27mm (one inch) in diameter (Childeric had some large fingers). On top is an oval bezel bearing the effigy of a beardless man with long hair parted in the center. He wears a paludamentum (a draped cloak fastened at one shoulder worn by Roman military leaders and emperors in statuary and on coinage) and holds a spear in his right hand. Around the head is the inscription CHILDERICI REGIS (Childeric King).

The signet ring was the proverbial smoking gun that identified the tomb as Childeric’s. It’s a heavy gold ring 27mm (one inch) in diameter (Childeric had some large fingers). On top is an oval bezel bearing the effigy of a beardless man with long hair parted in the center. He wears a paludamentum (a draped cloak fastened at one shoulder worn by Roman military leaders and emperors in statuary and on coinage) and holds a spear in his right hand. Around the head is the inscription CHILDERICI REGIS (Childeric King).

More than 300 golden bees with red glass wings were also found that are thought to have adorned Childeric’s ceremonial cloak. Centuries later, when Napoleon Bonaparte was about to be crowned Emperor of the French, he turned to the most ancient French monarch for iconography that would connect him to royal history while bypassing the still-loathed Bourbons and their fleur-de-lys. Napoleon adopted Childeric’s heraldry as his own. His coronation robe was embroidered with 300 gold bees and bees became the symbol of the new French Empire.

More than 300 golden bees with red glass wings were also found that are thought to have adorned Childeric’s ceremonial cloak. Centuries later, when Napoleon Bonaparte was about to be crowned Emperor of the French, he turned to the most ancient French monarch for iconography that would connect him to royal history while bypassing the still-loathed Bourbons and their fleur-de-lys. Napoleon adopted Childeric’s heraldry as his own. His coronation robe was embroidered with 300 gold bees and bees became the symbol of the new French Empire.

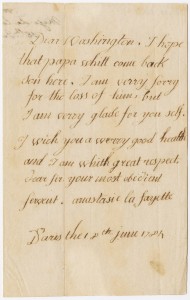

When Childeric’s treasure was discovered, Tournai was part of the Spanish Netherlands, governed by Archduke Leopold Wilhelm of Austria, younger brother of Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand III. The bulk of Childeric’s grave goods (there was much pilfering, apparently, during the dig) went to the Archduke who had the great good sense to order his physician Jean-Jacques Chifflet to document every piece thoroughly. Chifflet’s meticulous study, complete with extremely detailed engravings of the artifacts, was published in 1655 as Anastasis Childerici I. Francorvm Regis, sive Thesavrvs Sepvlchralis Tornaci Neruiorum (The Resurrection of Childeric the First, King of the Franks, or the Funerary Treasure of Tournai of the Nervians). Dependant on ancient sources and comparisons with other artifacts, Chifflet made some errors and misidentified some of the pieces, but his careful recording of every object is today considered the first scientific archaeological publication before there was such a thing as archaeological science.

When Childeric’s treasure was discovered, Tournai was part of the Spanish Netherlands, governed by Archduke Leopold Wilhelm of Austria, younger brother of Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand III. The bulk of Childeric’s grave goods (there was much pilfering, apparently, during the dig) went to the Archduke who had the great good sense to order his physician Jean-Jacques Chifflet to document every piece thoroughly. Chifflet’s meticulous study, complete with extremely detailed engravings of the artifacts, was published in 1655 as Anastasis Childerici I. Francorvm Regis, sive Thesavrvs Sepvlchralis Tornaci Neruiorum (The Resurrection of Childeric the First, King of the Franks, or the Funerary Treasure of Tournai of the Nervians). Dependant on ancient sources and comparisons with other artifacts, Chifflet made some errors and misidentified some of the pieces, but his careful recording of every object is today considered the first scientific archaeological publication before there was such a thing as archaeological science.

Archduke Leopold brought Childeric’s treasure with him to Vienna when he left the Spanish Netherlands in 1656. Upon his death in 1662, he bequeathed his extensive gallery of art and artifacts, including Childeric’s grave goods, to his nephew, Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I. In 1665, Leopold I gifted the Childeric treasure to King Louis XIV in gratitude for his military aid against the Ottoman Empire in Hungary the year before. Louis, reportedly unimpressed by the 5th century version of luxury goods, had them stored in his Cabinet of Medals in the Louvre palace. After the French Revolution, Childeric’s treasure became part of the Cabinet of Medals of the Imperial Library, later the Royal Library, now the National Library.

Archduke Leopold brought Childeric’s treasure with him to Vienna when he left the Spanish Netherlands in 1656. Upon his death in 1662, he bequeathed his extensive gallery of art and artifacts, including Childeric’s grave goods, to his nephew, Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I. In 1665, Leopold I gifted the Childeric treasure to King Louis XIV in gratitude for his military aid against the Ottoman Empire in Hungary the year before. Louis, reportedly unimpressed by the 5th century version of luxury goods, had them stored in his Cabinet of Medals in the Louvre palace. After the French Revolution, Childeric’s treasure became part of the Cabinet of Medals of the Imperial Library, later the Royal Library, now the National Library.

During the night of November 5th 1831, thieves broke into the Cabinet of Medals of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France and stole more than 2,000 gold objects for a total weight of 80 kilos, including all of Childeric’s treasure. Accounts of what happened afterwards differ because many of the records were destroyed during the Paris Commune of 1871. Either a couple of suspects were arrested within a few days of the theft and refused to talk leaving the police to search for the treasures for 8 months, or the police searched 8 months before finding the culprits and what was left of the treasure. Whichever way it went, the theft was a huge scandal and the police were under great pressure to come up with results. They even enlisted the aid of the legendary Eugène-François Vidocq, head of the Sûreté, Paris’ first-of-its-kind plainclothes detective bureau that he had founded in 1812. Vidocq had quit in 1827 but was reappointed head of the Sûreté in early 1832 and he and his team were on the Childeric case.

During the night of November 5th 1831, thieves broke into the Cabinet of Medals of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France and stole more than 2,000 gold objects for a total weight of 80 kilos, including all of Childeric’s treasure. Accounts of what happened afterwards differ because many of the records were destroyed during the Paris Commune of 1871. Either a couple of suspects were arrested within a few days of the theft and refused to talk leaving the police to search for the treasures for 8 months, or the police searched 8 months before finding the culprits and what was left of the treasure. Whichever way it went, the theft was a huge scandal and the police were under great pressure to come up with results. They even enlisted the aid of the legendary Eugène-François Vidocq, head of the Sûreté, Paris’ first-of-its-kind plainclothes detective bureau that he had founded in 1812. Vidocq had quit in 1827 but was reappointed head of the Sûreté in early 1832 and he and his team were on the Childeric case.

(They were on a lot of other cases at the same time, like ruthlessly suppressing the June Rebellion in Paris after the death from cholera of General Jean Maximilien Lamarque. Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables was set against the backdrop of this rebellion and Vidocq was the inspiration for Javert. He was the inspiration for Valjean as well, believe it or not, because he had been a criminal in his youth, done hard labour in the galleys of Brest, escaped, been caught, escaped again, got caught again, did more time before finally turning his particular set of skills to the aid of law enforcement by becoming an informant. He parlayed that into undercover detective work. Under him, the Sûreté was staffed by convicts operating under the it-takes-one-to-know-one premise. It was highly effective. Crime rates in Paris dropped 40% after the Sûreté began doing its thing. Vidocq was also the inspiration for the character of C. Auguste Dupin in Edgar Allen Poe’s The Murders in the Rue Morgue, the first detective story.)

![]() Anyway, eight months after the theft, the police busted a gang of thieves and found 20 ingots of gold in their hideout. Upon interrogation the thieves admitted they had melted down the pure gold objects into ingots while those with inlaid stones or that were harder to melt down for whatever reason were put in sacs of leather and immersed in the Seine either at the Pont Marie or the Pont de la Tournelle. (The bridges are in the same spot on the Seine. The Pont Marie connects the Île Saint-Louis to the Right Bank; the Pont de la Tournelle is its mirror, connecting the island to the Left Bank.) When the police dragged the river, they found eight bags holding around 1,500 pieces of the 2,000 stolen, 75 of the 80 kilos. Added to the ingot weight, the recovered objects were determined to be the entirety of the burgled treasure and the case was closed. In January of 1833, three of the thieves were convicted of the crime. One was sentenced to 40 years in prison, one to 20 years, one to 10.

Anyway, eight months after the theft, the police busted a gang of thieves and found 20 ingots of gold in their hideout. Upon interrogation the thieves admitted they had melted down the pure gold objects into ingots while those with inlaid stones or that were harder to melt down for whatever reason were put in sacs of leather and immersed in the Seine either at the Pont Marie or the Pont de la Tournelle. (The bridges are in the same spot on the Seine. The Pont Marie connects the Île Saint-Louis to the Right Bank; the Pont de la Tournelle is its mirror, connecting the island to the Left Bank.) When the police dragged the river, they found eight bags holding around 1,500 pieces of the 2,000 stolen, 75 of the 80 kilos. Added to the ingot weight, the recovered objects were determined to be the entirety of the burgled treasure and the case was closed. In January of 1833, three of the thieves were convicted of the crime. One was sentenced to 40 years in prison, one to 20 years, one to 10.

Devastatingly, Childeric’s treasure was almost entirely lost. Authorities recovered two coins, two bees and the gold and garnet cloisonné fittings from Childeric’s sword and scramasax. The signet ring was gone, only surviving as reproductions made by the Habsburgs and in imprints taken of the seal. Chifflet’s recorded data and illustrations are virtually all that remains of this historic treasure

Devastatingly, Childeric’s treasure was almost entirely lost. Authorities recovered two coins, two bees and the gold and garnet cloisonné fittings from Childeric’s sword and scramasax. The signet ring was gone, only surviving as reproductions made by the Habsburgs and in imprints taken of the seal. Chifflet’s recorded data and illustrations are virtually all that remains of this historic treasure

One of the recovered artifacts from the 1831 theft at the Bibliothèque Nationale is actually in the United States right now. The Rennes patera, an early 3rd century Roman shallow libation bowl made of no less than three pounds of very pure solid 23-carat gold, somehow survived being melted down in the thieves’ initial orgy of ingot production. It was loaned by National Library to the Getty Villa in Malibu for the Ancient Luxury and the Roman Silver Treasure from Berthouville exhibition and will be in California through August 17th before returning to Paris.

One of the recovered artifacts from the 1831 theft at the Bibliothèque Nationale is actually in the United States right now. The Rennes patera, an early 3rd century Roman shallow libation bowl made of no less than three pounds of very pure solid 23-carat gold, somehow survived being melted down in the thieves’ initial orgy of ingot production. It was loaned by National Library to the Getty Villa in Malibu for the Ancient Luxury and the Roman Silver Treasure from Berthouville exhibition and will be in California through August 17th before returning to Paris.