The University of Virginia Rotunda building, originally designed by Thomas Jefferson, has been undergoing an extensive renovation since 2012. The $58.3 million project has already replaced the steel panels of the dome with copper, repaired the exterior the brick work and window sashes, and is now focusing on the interior. While checking the walls of one of the basement rooms, workers found a chemistry hearth dating to the original Jefferson-era building from the 1820s. Brian Hogg, senior historic preservation planner of the university’s Office of the Architect, believes the hearth “oldest intact example of early chemical education” in the United States.

The University of Virginia Rotunda building, originally designed by Thomas Jefferson, has been undergoing an extensive renovation since 2012. The $58.3 million project has already replaced the steel panels of the dome with copper, repaired the exterior the brick work and window sashes, and is now focusing on the interior. While checking the walls of one of the basement rooms, workers found a chemistry hearth dating to the original Jefferson-era building from the 1820s. Brian Hogg, senior historic preservation planner of the university’s Office of the Architect, believes the hearth “oldest intact example of early chemical education” in the United States.

The chemical hearth was built as a semi-circular niche in the north end of the Lower East Oval Room. Two fireboxes provided heat (one burning wood for fuel, the other burning coal), underground brick tunnels fed fresh air to fireboxes and workstations, and flues carried away the fumes and smoke. Students worked at five workstations cut into stone countertops.

The chemical hearth was built as a semi-circular niche in the north end of the Lower East Oval Room. Two fireboxes provided heat (one burning wood for fuel, the other burning coal), underground brick tunnels fed fresh air to fireboxes and workstations, and flues carried away the fumes and smoke. Students worked at five workstations cut into stone countertops.

Jefferson arranged for the chemistry laboratory to be placed in the basement because of the danger of running furnaces on the upper floors. John Emmet, UVA’s first professor of natural history, after finding the small room assigned to be his lab far too hot for use in experiments, was given both the large basement rooms for his classes in June of 1825. He used the Lower East Oval Room for experiments and demos and the Lower West Oval Room for lectures.

Jefferson arranged for the chemistry laboratory to be placed in the basement because of the danger of running furnaces on the upper floors. John Emmet, UVA’s first professor of natural history, after finding the small room assigned to be his lab far too hot for use in experiments, was given both the large basement rooms for his classes in June of 1825. He used the Lower East Oval Room for experiments and demos and the Lower West Oval Room for lectures.

Thomas Jefferson’s vision for a new system of public education was one rigorous enough to compete with the ancient and prestigious universities of Europe while avoiding their aristocratic trappings and structural inadequacies. He described this vision in a letter to the Trustees for the Lottery of East Tennessee College from May 6th, 1810:

I consider the common plan followed in this country, but not in others, of making one large and expensive building, as unfortunately erroneous. It is infinitely better to erect a small and separate lodge for each separate professorship with only a hall below for his class, and two chambers above for himself; joining these lodges by barracks for a certain portion of the students, opening into a covered way to give a dry communication between all the schools. The whole of these arranged around an open square of grass and trees, would make it, what it should be in fact, an academical village, instead of a large and common den of noise, of filth and of fetid air. It would afford that quiet retirement so friendly to study, and lessen the dangers of fire, infection and tumult.

It would be seven years before Jefferson acquired the land for what would become the University of Virginia, but his vision of a community of learning was undimmed. He designed the Rotunda, modeled after the Pantheon in Rome, to be the literal and figurative center of the academic village, the university library flanked by faculty pavilions and student dorms.

It would be seven years before Jefferson acquired the land for what would become the University of Virginia, but his vision of a community of learning was undimmed. He designed the Rotunda, modeled after the Pantheon in Rome, to be the literal and figurative center of the academic village, the university library flanked by faculty pavilions and student dorms.

Construction began in 1822 and was still ongoing when Jefferson died in 1826. The building had issues from the beginning — the dome leaked — and the needs of the students soon outgrew the space. Two wings of the Rotunda used as covered exercise yards were converted into classrooms in 1841. A four-story annex was built between 1851 and 1854 to provide additional classroom space, laboratory space and an auditorium. Water from the perpetually leaking roof and from an ill-fated scheme to install two 7,000-gallon water tanks under the dome for campus use damaged the walls and ceilings.

Construction began in 1822 and was still ongoing when Jefferson died in 1826. The building had issues from the beginning — the dome leaked — and the needs of the students soon outgrew the space. Two wings of the Rotunda used as covered exercise yards were converted into classrooms in 1841. A four-story annex was built between 1851 and 1854 to provide additional classroom space, laboratory space and an auditorium. Water from the perpetually leaking roof and from an ill-fated scheme to install two 7,000-gallon water tanks under the dome for campus use damaged the walls and ceilings.

Then, on October 27th, 1895, fire struck. It started in the annex, likely caused by faulty electrical wiring. Engineering professor William H. Echols tried to save the Rotunda by dynamiting the connector linking the annex to the original building. The plan backfired horribly when the explosion blew a hole in the Rotunda which injected fresh new oxygen into the conflagration. When the last of the flames were extinguished, the annex was destroyed, the dome was gone and the Rotunda was gutted. Only the brick walls and columns were left standing.

Then, on October 27th, 1895, fire struck. It started in the annex, likely caused by faulty electrical wiring. Engineering professor William H. Echols tried to save the Rotunda by dynamiting the connector linking the annex to the original building. The plan backfired horribly when the explosion blew a hole in the Rotunda which injected fresh new oxygen into the conflagration. When the last of the flames were extinguished, the annex was destroyed, the dome was gone and the Rotunda was gutted. Only the brick walls and columns were left standing.

The task of reconstructing the Rotunda was assigned in 1896 to the New York architectural firm of McKim, Mead and White, specifically to Gilded Age trendsetter Stanford White who 10 years later would be scandalously murdered on the roof of his own Madison Square Garden. White changed the building in major ways: he widened the oculus, gave the interior two floors instead of Jefferson’s three, enlarging the Dome Room, installed new heating and ventilation systems, used fireproof materials, changed the portico columns to thicker pillars with new Corinthian capitals. In 1976 the Rotunda was gutted and rebuilt in keeping with Jefferson’s original design.

The task of reconstructing the Rotunda was assigned in 1896 to the New York architectural firm of McKim, Mead and White, specifically to Gilded Age trendsetter Stanford White who 10 years later would be scandalously murdered on the roof of his own Madison Square Garden. White changed the building in major ways: he widened the oculus, gave the interior two floors instead of Jefferson’s three, enlarging the Dome Room, installed new heating and ventilation systems, used fireproof materials, changed the portico columns to thicker pillars with new Corinthian capitals. In 1976 the Rotunda was gutted and rebuilt in keeping with Jefferson’s original design.

Given this history, the odds against anything at all from the Rotunda of 1826 surviving are astronomical. What saved the chemistry hearth was its having been walled up before the construction of the annex, probably in the 1840s when the chem lab was moved to the southwest excercise yard after it was converted into classroom space.

Given this history, the odds against anything at all from the Rotunda of 1826 surviving are astronomical. What saved the chemistry hearth was its having been walled up before the construction of the annex, probably in the 1840s when the chem lab was moved to the southwest excercise yard after it was converted into classroom space.

The university is embracing this unique find from its earliest days. The plan is to rebuild the original arch above the entrance to the hearth space and to create some sort of barrier to keep people from stepping into the alcove, but to leave the hearth itself as it is now for display.

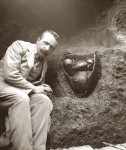

The restoration of the golden funerary mask of King Tutankhamun has begun after last year’s botched attempted to reattach the false beard left it with a thick, ugly layer of visible epoxy glue and scratches on the gold. The mask was removed from public view on the second floor of the Egyptian Museum two weeks ago and moved to a laboratory. A team of German and Egyptian conservators led by Christian Eckmann examined it thoroughly, using a microscope to assess its condition and figuring out how best to approach the removal of the epoxy without damaging the gold.

The restoration of the golden funerary mask of King Tutankhamun has begun after last year’s botched attempted to reattach the false beard left it with a thick, ugly layer of visible epoxy glue and scratches on the gold. The mask was removed from public view on the second floor of the Egyptian Museum two weeks ago and moved to a laboratory. A team of German and Egyptian conservators led by Christian Eckmann examined it thoroughly, using a microscope to assess its condition and figuring out how best to approach the removal of the epoxy without damaging the gold.“We have some uncertainties now, we don’t know how deep the glue went inside the beard, and so we don’t know how long it will take to remove the beard,” [Christian Eckmann] said on the sidelines of a news conference with the antiquities minister, Mamdouh el-Damaty, and Tarek Tawfik, director-general of the still-under-construction Grand Egyptian Museum near the pyramids.

The process of removing the beard by scraping away the glue with wooden sticks could take at least a month. Once the thick glue layer has been removed, the team will study how to reattach the beard. The beard has a pin that fits into a slot on the chin, but it’s been loose since Howard Carter discovered it in 1922. A 1941 restoration added a thin layer of adhesive to keep the beard stable. In the seven decades since then, the adhesive weakened, which is likely why the beard fell off when it was jostled last year during routine work on the display’s lighting. A joint scientific committee will decide the best method of reattachment.

The process of removing the beard by scraping away the glue with wooden sticks could take at least a month. Once the thick glue layer has been removed, the team will study how to reattach the beard. The beard has a pin that fits into a slot on the chin, but it’s been loose since Howard Carter discovered it in 1922. A 1941 restoration added a thin layer of adhesive to keep the beard stable. In the seven decades since then, the adhesive weakened, which is likely why the beard fell off when it was jostled last year during routine work on the display’s lighting. A joint scientific committee will decide the best method of reattachment.  There are two components to the restoration project: the detachment/reattachment of the beard, and a comprehensive study of the materials and techniques used to manufacture the mask. While the gold mask of Tutankhamun has been one of the most photographed artifacts in the world since its discovery, it has never been thoroughly documented and studied with modern scientific methods. Having to repair this reprehensible conservation disaster does therefore have something of a silver lining.

There are two components to the restoration project: the detachment/reattachment of the beard, and a comprehensive study of the materials and techniques used to manufacture the mask. While the gold mask of Tutankhamun has been one of the most photographed artifacts in the world since its discovery, it has never been thoroughly documented and studied with modern scientific methods. Having to repair this reprehensible conservation disaster does therefore have something of a silver lining.