In 1931, star of stage and screen John Barrymore sailed to Alaska aboard his new 120-foot yacht the Infanta. His purpose was to hunt Kodiak bear, but he took a different kind of trophy when he visited the village of Tuxecan on Prince of Wales Island in southeastern Alaska: a totem pole 25 feet high. Barrymore had the pole sawn down leaving just a stump behind, then had it sawn into three sections to make it easier to carry on the deck of his yacht. Once home, the actor installed the totem pole on the grounds of his Beverly Hills estate, Bella Vista.

In 1931, star of stage and screen John Barrymore sailed to Alaska aboard his new 120-foot yacht the Infanta. His purpose was to hunt Kodiak bear, but he took a different kind of trophy when he visited the village of Tuxecan on Prince of Wales Island in southeastern Alaska: a totem pole 25 feet high. Barrymore had the pole sawn down leaving just a stump behind, then had it sawn into three sections to make it easier to carry on the deck of his yacht. Once home, the actor installed the totem pole on the grounds of his Beverly Hills estate, Bella Vista.

Tuxecan had been abandoned 30 years earlier when a clan leader convinced the Tlingit tribe members who lived there to move south to the town of Klawock where there was a new school and the state’s first cannery. They left behind a forest of totem poles which the villagers occasionally returned to tend to, but over time began to tip over and decay, a process that the Tlingit held to be part of the natural lifecycle of kooteeyaa (totem poles).

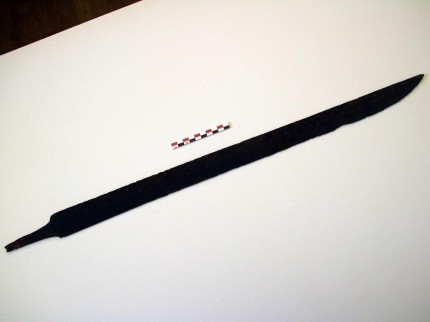

Tlingit totem poles were carved from single trunks of Western red cedar and raised outside people’s homes. The animals from a clan’s crest were carved on the poles, but each one had a different combination of figures and a different meaning. They celebrated family history, could commemorate a person or event or broadcast a wrong done to the pole’s owner. Some were funerary monuments that included the ashes of the dead in bentwood boxes placed in niches in the back the pole. While the were not objects of religious veneration per se, they were and are held to be sacred.

The higher the pole, the more prestigious it was. The highest poles in Tuxecan reached 30 feet or so, which means the 25-footer Barrymore stole was a very important piece in its day. Its importance has only increased with the passage of time and the loss of almost all of the more than 100 totem poles that once graced Tuxecan. Only two other original totem poles survived, moved to Klawock along with the tribe at the turn of the last century.

The totem pole makes an ominous appearance in Gene Fowler’s biography of John Barrymore, Good Night, Sweet Prince. Barrymore was warned that removing the totem pole would bring him back luck, and Barrymore, who had an interest in diverse religious traditions, was somewhat concerned that the tribal gods “might take a notion into their whimsical noggins to wreak vengeance on the thief.” If they did, they used his preexisting alcohol addiction to get to him. John Barrymore died of cirrhosis of the liver in 1942.

The Barrymore estate was sold after his death, and the pole was bought by collector Ralph Altman. Altman sold it in the 1950s to actor, art historian and dedicated collector Vincent Price who had it installed next to his patio in his quarter-acre backyard in Benedict Canyon. Price loved it dearly, including photos of it in his books and showing it off to Edward R. Murrow in a 1958 episode of Person to Person. He described it in his memoirs as “sculptural and dignified and beautiful” with “its lovely warm browns and reds still glowing on the three great figures which compose its height. At the bottom a great bear-like creature, paws pleading; and on his head, a pale lean man who holds before him a gigantic fish which reaches from his shoulders to his toes; and on his head, hawk-nosed and savage, crouches a great bird, his tail behind him abristle with red feathers made of shingling.”

The Barrymore estate was sold after his death, and the pole was bought by collector Ralph Altman. Altman sold it in the 1950s to actor, art historian and dedicated collector Vincent Price who had it installed next to his patio in his quarter-acre backyard in Benedict Canyon. Price loved it dearly, including photos of it in his books and showing it off to Edward R. Murrow in a 1958 episode of Person to Person. He described it in his memoirs as “sculptural and dignified and beautiful” with “its lovely warm browns and reds still glowing on the three great figures which compose its height. At the bottom a great bear-like creature, paws pleading; and on his head, a pale lean man who holds before him a gigantic fish which reaches from his shoulders to his toes; and on his head, hawk-nosed and savage, crouches a great bird, his tail behind him abristle with red feathers made of shingling.”

Price donated the totem pole to the Honolulu Museum of Art in 1981. The museum didn’t have space to exhibit the entire pole, so the top third was on display in the museum’s Kinau Courtyard while the rest was kept in climate-controlled storage. The top third joined its two brothers in storage 12 years ago when it was taken down during a renovation.

Price donated the totem pole to the Honolulu Museum of Art in 1981. The museum didn’t have space to exhibit the entire pole, so the top third was on display in the museum’s Kinau Courtyard while the rest was kept in climate-controlled storage. The top third joined its two brothers in storage 12 years ago when it was taken down during a renovation.

Meanwhile, University of Alaska Anchorage anthropology professor and Tlingit expert Steve Langdon stumbled on the totem pole in the 1990s while researching the Tlingit villages of Prince of Wales Island in a Ketchikan museum. He was looking through some old photographs when he came across a snapshot of Vincent Price standing in front of the totem pole. The cactuses indicated that this picture had not been taken in Alaska. Langdon consulted with Jonathan Rowan, a carver and cultural educator from Klawock, who helped him identify the pole in photographs of Tuxecan from the late 19th century.

Langdon, with the blessing of Tlingit leaders, visited the Honolulu Museum of Art in 2013 with his evidence in tow. Museum director Stephan Jost recognized that Langdon had the goods. A formal investigation by the museum determined that the totem pole was indeed an object of cultural patrimony and the official repatriation process began in January of this year. On Thursday, October 22nd, the kooteeyaa was formally returned to Tlingit tribal members including Jonathan Rowan and his daughter Eva in a ceremony at the Honolulu museum. This week it sails for Alaska.

Langdon, with the blessing of Tlingit leaders, visited the Honolulu Museum of Art in 2013 with his evidence in tow. Museum director Stephan Jost recognized that Langdon had the goods. A formal investigation by the museum determined that the totem pole was indeed an object of cultural patrimony and the official repatriation process began in January of this year. On Thursday, October 22nd, the kooteeyaa was formally returned to Tlingit tribal members including Jonathan Rowan and his daughter Eva in a ceremony at the Honolulu museum. This week it sails for Alaska.

Once home, the totem pole will be studied by Rowan and other experts in an attempt to identify which clan it originally belonged to and whether it was a mortuary monument. Altman told Price that it was, that the yacht crew members who cut it down “threw Mom and Dad in the creek” before sawing it in three. It will be difficult to determine whether it was a funerary piece because at some point during its California sojourn the back was back dug out to insert a pair of metal stabilizing rods and Barrymore had converted it into a fountain. Correcting Price’s understanding of the animals and identifying the crest is less daunting. Rowan believes from the photographs that the “bear-like creature” at the bottom may be a wolf, the “gigantic fish” is almost certainly a killer whale and the bird up top is an eagle.

Once home, the totem pole will be studied by Rowan and other experts in an attempt to identify which clan it originally belonged to and whether it was a mortuary monument. Altman told Price that it was, that the yacht crew members who cut it down “threw Mom and Dad in the creek” before sawing it in three. It will be difficult to determine whether it was a funerary piece because at some point during its California sojourn the back was back dug out to insert a pair of metal stabilizing rods and Barrymore had converted it into a fountain. Correcting Price’s understanding of the animals and identifying the crest is less daunting. Rowan believes from the photographs that the “bear-like creature” at the bottom may be a wolf, the “gigantic fish” is almost certainly a killer whale and the bird up top is an eagle.

If you’d like to learn more about the totem pole saga, Steve Langdon’s lecture at the University of Alaska Anchorage last year is on YouTube in two parts.

[youtube=https://youtu.be/NrWMzZ_8ndA&w=430]

[youtube=https://youtu.be/zVDn8plIALw&w=430]