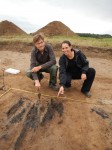

The 10th century Borgring fortress discovered on the Danish island of Zealand last year was identified by a geomagnetic survey and a few test pits dug at the gates and ramparts. There are only seven ring fortresses of the Trelleborg type known to exist, and the last one was found 60 years ago. The discovery of Borgring 30 miles south of Copenhagen was exciting because of its rarity and because it opened up the possibility of an excavation done with the latest archaeological technology.

The 10th century Borgring fortress discovered on the Danish island of Zealand last year was identified by a geomagnetic survey and a few test pits dug at the gates and ramparts. There are only seven ring fortresses of the Trelleborg type known to exist, and the last one was found 60 years ago. The discovery of Borgring 30 miles south of Copenhagen was exciting because of its rarity and because it opened up the possibility of an excavation done with the latest archaeological technology.

The Danish Castle Centre will bring that possibility to life, thanks to a 20 million kroner (ca. $3 million) grant from the AP Møller Fund and 4.5 million kroner (ca. $687,000) from Køge Municipality. These generous gifts will fund a three-year excavation of the Borgring fortress.

“With the grant, the Danish Castle Centre – a division of Museum Southeast Denmark and Aarhus University – has worked out a unique research project seeking to explore the secrets Borgring is hiding beneath Danish soil,” the Danish Castle Centre said.

“With the use of modern archaeological methods the scientists and archaeologists will investigate how the fortresses were used, how they were organised, how quickly they were built, their age and what environment, landscape and geography they were a part of.”

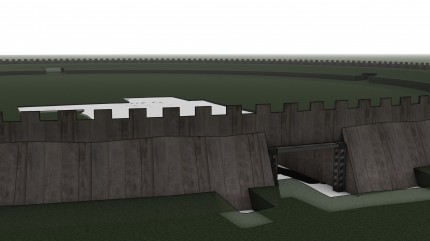

So far, it has become clear that the massive ring fortress has a diameter of 142 metres with 7 metre-high palisades, while it also endured a fiery blaze at one of its gates.

The Trelleborg fortresses were all built according to the same geometric plan — circular with gates aligned on the cardinal compass points — within an hour’s march of each other. Counting tree rings at the type site of Trelleborg pinpointed the construction date to early 981 since the timbers were felled in autumn of 980 and would have needed some time to cure before use. The other fortresses date to approximately the same time, and their strikingly similar design and aligned placement suggests they were conceived by a single mind.

There are some anomalies with the Borgring, however. Its gates are not perfectly aligned along the cardinal points; there is an 11-degree dislocation which may have been a topographical necessity to ensure that it looked properly symmetrical in its landscape. Also samples of burned oak timbers found at the north gate were radiocarbon dated to between 895 and 1017 A.D., which places the fort in the general age range of the other trelleborgs but isn’t precise enough to confirm that it is in fact one of them. Dendrochronological analysis can narrow it down further.

There are some anomalies with the Borgring, however. Its gates are not perfectly aligned along the cardinal points; there is an 11-degree dislocation which may have been a topographical necessity to ensure that it looked properly symmetrical in its landscape. Also samples of burned oak timbers found at the north gate were radiocarbon dated to between 895 and 1017 A.D., which places the fort in the general age range of the other trelleborgs but isn’t precise enough to confirm that it is in fact one of them. Dendrochronological analysis can narrow it down further.

The precise date is important with these fortresses because the most prevalent theory right now about their construction is that they were built by King Harald Bluetooth in reaction to his defeat at German hands in 974. To defend his territory from further incursions, Bluetooth set about building an extensive network of forts and infrastructure (bridges, roads) in Denmark and southern Sweden. Harald Bluetooth died in 985 or 986, just five or six years after the first Trelleborg ringfort was built. If Harald didn’t build them, his son Sweyn Forkbeard may have, not as a defensive installation to keep out the Germans, but as military training camps to prepare his troops for his raids on England in the first decade of the 11th century and his full-scale invasion of the island in 1013.

The excavation is slated to begin next year and with the fortress being a short distance from the highway so close to Copenhagen, the archaeological team is expecting a significant amount of interest from the public. The team plans to build an observation deck so visitors can follow the archaeologists at work without getting in their way.