A rare printed copy of Christopher Columbus’ letter describing what the people and placed he’d found on his famous transatlantic voyage that was stolen from the Riccardiana Library in Florence, Italy, has been found in the Library of Congress and returned to Italy. Nobody knows exactly when the red leather-bound volume that included the letter along with other early printed texts from the 1490s was stolen because it was replaced with a forgery that looked surprisingly plausible despite having been printed from a photographic plate.

A rare printed copy of Christopher Columbus’ letter describing what the people and placed he’d found on his famous transatlantic voyage that was stolen from the Riccardiana Library in Florence, Italy, has been found in the Library of Congress and returned to Italy. Nobody knows exactly when the red leather-bound volume that included the letter along with other early printed texts from the 1490s was stolen because it was replaced with a forgery that looked surprisingly plausible despite having been printed from a photographic plate.

The director of the library, Fulvio Silvano Stacchetti, suspects it was stolen in 1950 or 1951 when it was on loan to the national library in Rome because that was only time in the recent past when it was out of their hands. Experts who have analyzed the forgery think the technology and materials used are newer than that, and what investigators have been able to trace of its history suggests a much more recent date for the theft. It was in the hands of a rare book collector in Switzerland in 1990 and was sold at Christie’s New York two years later for $330,000. In 2004 it was bequeathed to the Library of Congress.

The forgery was first spotted in 2012, when an unnamed individual doing research in the library’s rare book room encountered the volume and thought it looked fishy. He reported his suspicions to the Department of Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) who contacted Italy’s crack Carabinieri Art Squad. Homeland Security Investigations Special Agent Mark Olexa, a specialist in cultural property theft, joined Carabinieri investigators and Italian experts in Florence in July of 2012 where they examined the forgery. They confirmed that it was indeed a fake, missing the Riccardiana library stamp, with the wrong sized pages, different page numbering, different stitching patterns compared to other prints of the letter, and on paper that while old, was a century younger than it should have been.

The forgery was first spotted in 2012, when an unnamed individual doing research in the library’s rare book room encountered the volume and thought it looked fishy. He reported his suspicions to the Department of Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) who contacted Italy’s crack Carabinieri Art Squad. Homeland Security Investigations Special Agent Mark Olexa, a specialist in cultural property theft, joined Carabinieri investigators and Italian experts in Florence in July of 2012 where they examined the forgery. They confirmed that it was indeed a fake, missing the Riccardiana library stamp, with the wrong sized pages, different page numbering, different stitching patterns compared to other prints of the letter, and on paper that while old, was a century younger than it should have been.

Investigators tracked the original letter to the Library of Congress where HSI agents worked with experts from the Smithsonian to confirm its real identity. They found evidence of deliberate attempts to disguise the true origin of the text. The stamp of the Riccardiana Library had been removed with chemical bleach and some of the characters altered to make them less recognizable at a glance. That’s why the American collector and Library of Congress had no idea it was stolen. (It wouldn’t have killed Christie’s to take a closer look, though, and I’ll bet dollars to donuts the Swiss dealer knew what was up.)

The investigation into the theft is still open, but on Wednesday, May 18th, the volume was formally returned to Italy in a ceremony at the Biblioteca Angelica in Rome. Italian Culture Minister Enrico Franceschini noted aptly: “It is interesting how 500 years after the letter was written it has made the same trip back and forth from America.”

The investigation into the theft is still open, but on Wednesday, May 18th, the volume was formally returned to Italy in a ceremony at the Biblioteca Angelica in Rome. Italian Culture Minister Enrico Franceschini noted aptly: “It is interesting how 500 years after the letter was written it has made the same trip back and forth from America.”

This is not a copy of the original letter written to Ferdinand and Isabella, as some of the articles are describing it, nor is it quite accurate to say that the original letter was lost, as other articles have said. I mentioned in this post about the fresco that may include a depiction of the first indigenous Americans in European art that Columbus is known to have written two letters with near-identical content, one addressed to King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, one to Spanish finance minister Luis de Santangel, Columbus’ patron and advocate. He sent both letters at the same time, either when he landed in Lisbon on March 4th or Palos on March 15th, 1493.

The original letter to Ferdinand and Isabella was never published, so far as we know, so there are no extant copies. The letter to Santangel made it to press within weeks. The earliest known edition of the Santangel letter was published in the original Spanish by Barcelona printer Pere Posa in April of 1493. It was believed lost until a copy was found in Spain in 1890. That copy is now in the rare book division of the New York Public Library.

The original letter to Ferdinand and Isabella was never published, so far as we know, so there are no extant copies. The letter to Santangel made it to press within weeks. The earliest known edition of the Santangel letter was published in the original Spanish by Barcelona printer Pere Posa in April of 1493. It was believed lost until a copy was found in Spain in 1890. That copy is now in the rare book division of the New York Public Library.

The Santangel letter quickly made its way to Rome where a Latin translation was printed by Stephen Plannck by May, 1493. Plannck printed a second edition that same year. There were several changes. The first edition had only King Ferdinand’s name in the introduction, thought to be a deliberate slight resulting from the Aragonese translator Aliander de Cosco’s disdain for Castille, and the second edition had the names of both Ferdinand and Isabella in the header. The second edition also changed the name of the recipient from Raphael Sanxis to Gabriel Sanchez (Aliander was translating the Posa Spanish edition of the Santangel letter, but he mistakenly thought the king’s treasurer Sanxis was the recipient instead of the finance minister Santangel) and Italianized the name of the translator to Leander di Cosco. The recovered letter is a Plannck II edition.

Between 1493 and 1497, 17 editions of the letter were printed. An estimated 3,000 copies were distributed in major cities throughout Europe. Very few of them, around 80, have survived. About 30 of them are Plannck II letters. The figures are approximate because as a highly sought-after document, forgeries of the letter abound and authenticity can be hard to determine.

The letter will now be returned to the Riccardiana Library. The Galata Sea Museum in Columbus’ hometown of Genoa has submitted a request to the Culture Ministry that they get the letter because they’ll put it on display instead of squirreling it away in an archive where so few people will see it that they won’t notice it’s been stolen and replaced with a forgery for decades.

The letter will now be returned to the Riccardiana Library. The Galata Sea Museum in Columbus’ hometown of Genoa has submitted a request to the Culture Ministry that they get the letter because they’ll put it on display instead of squirreling it away in an archive where so few people will see it that they won’t notice it’s been stolen and replaced with a forgery for decades.

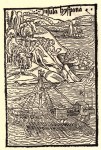

You can read the full text of the Santangel Columbus Letter in the original Spanish and translated into English here. This book compiled by the Lenox Library (later absorbed into the NYPL) starts with a reprint of the one pictorial edition with woodcuts said to have been drawn by Columbus himself, and a neat comparison of the four Latin editions, including both Planncks.