One of the gems in the British Museum is the statue of Idrimi, King of Alalakh, an ancient city-state in what is now Turkey, in the 15th century B.C. Destroyed in 1200 B.C., probably by the Sea People, Alalakh was never rebuilt. The remains of the city are today the archaeological site of Tell Atchana, which was first excavated by famed archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley in the 1930s. The statue of Idrimi was unearthed by Woolley in the remains of a temple during the 1939 dig season.

One of the gems in the British Museum is the statue of Idrimi, King of Alalakh, an ancient city-state in what is now Turkey, in the 15th century B.C. Destroyed in 1200 B.C., probably by the Sea People, Alalakh was never rebuilt. The remains of the city are today the archaeological site of Tell Atchana, which was first excavated by famed archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley in the 1930s. The statue of Idrimi was unearthed by Woolley in the remains of a temple during the 1939 dig season.

Woolley described the find in a dispatch on May 21st, 1939:

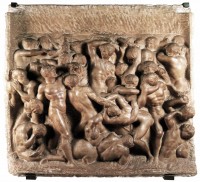

“A rubbish-pit at the temple gave us great surprise. From it there came a white stone statue just over a metre high of a Hittite king, a seated figure; the head and feet were broken off but except for part of the foot the statue is complete and in wonderfully good condition and even the nose is only just chipped. The figure is covered literally from head to foot with cuneiform inscription which begins on one cheek, runs across the front and one side of the body and ends at the bottom of the skirt, rather more than fifty lines of text. Nothing like that has been found before.”

Nothing like that has been found since. The Akkadian language inscription (pdf of translation here) is a detailed autobiography of Idrimi’s life and military conquests. Its chronology of monarchs, wars and population shifts remains to this day the primary source for the history of the Levant in the 15th century B.C. According to the inscription, Idrimi was born in Halab, modern-day Aleppo, Syria, part of the kingdom of Yamhad, the youngest of seven sons of a prince. Driven out of Aleppo by an unspecified “outrage,” Idrimi and his family fled to Emar where their maternal aunts lived, but Idrimi couldn’t tolerate going from prince to the poor relation; so he took his groom and chariot and joined up with groups of nomads in Canaan who recognized his noble lineage and acknowledged him as their ruler. This is the first known written reference to the Land of Canaan.

Nothing like that has been found since. The Akkadian language inscription (pdf of translation here) is a detailed autobiography of Idrimi’s life and military conquests. Its chronology of monarchs, wars and population shifts remains to this day the primary source for the history of the Levant in the 15th century B.C. According to the inscription, Idrimi was born in Halab, modern-day Aleppo, Syria, part of the kingdom of Yamhad, the youngest of seven sons of a prince. Driven out of Aleppo by an unspecified “outrage,” Idrimi and his family fled to Emar where their maternal aunts lived, but Idrimi couldn’t tolerate going from prince to the poor relation; so he took his groom and chariot and joined up with groups of nomads in Canaan who recognized his noble lineage and acknowledged him as their ruler. This is the first known written reference to the Land of Canaan.

After seven years of vicissitudes and sacrifices to the god Teshub, Idrimi finally reclaimed his ancestral heritage and became king of Alalakh. Many conquests, much booty and the construction of great palaces and temple followed. Alalakh prospered for 30 years under Idrimi’s rule. At the bottom of the inscription, Idrimi threatened dire consequences to anyone who would seek to erase this record of his achievements or claim it as their own.

He who removes this my statue, , may the sky curse him, may his seed be closed in the underworld, may the Gods of sky and earth divide his kingdom and his country! He who always changes it, in any way whatever, may Teshub, the lord of the sky and the earth and the great gods in his land, destroy his name and his descendants!

There’s another coda to the inscription, this one anomalously carved into his cheek so it looks like the cuneiform version of a speech bubble.

Thirty years long I was king. I wrote my acts on my tablet. One may look at it and constantly think of my blessing!

That goal will now be fulfilled on a vastly greater scale than Idrimi could ever have imagined. The statue has been in the permanent collection of the British Museum since it was excavated. Its surface is so fragile that to preserve the inscription the statue is on display behind protective glass. Not even researchers are allowed to get behind the glass, which means the inscription has not been able to benefit from the latest scholarship on Akkadian cuneiform.

Scanning technology has stepped into the breach. For two days, Idrimi was liberated from his enclosure so experts from the Factum Foundation could 3D-scan the statue using close-range photogrammetry and white light scanning. With every minute detail of the surface captured, the data was used to generate a 3D model available online to anyone in the world who wants to examine the statue.

Scanning technology has stepped into the breach. For two days, Idrimi was liberated from his enclosure so experts from the Factum Foundation could 3D-scan the statue using close-range photogrammetry and white light scanning. With every minute detail of the surface captured, the data was used to generate a 3D model available online to anyone in the world who wants to examine the statue.

It is encased in glass because “dust contains moisture, which wears away the natural laminates in the stone”, [Curator for the Levant at the British Museum James] Fraser says. It is carved from magnesite — a soft, brittle stone that may have been chosen because it was easy to carve. The glass barrier also prevents close study of the text. Instead, scholars have had to rely on old photographs and transliterations of the text to aid their research. “The digital model will revolutionise access to the object,” he says. It will also act a great touchstone for conservators because it is an accurate representation of the object’s condition as of 2017.

James Fraser gives a brief tour of the inscription during the short time Idrimi was out of his enclosure for the scanning in this video:

And now for Idrimi in his full 3D scan glory. Get your ancient king’s blessing here!

Incidentally, Idrimi is in excellent company on the British Museum’s Sketchfab page. There are 3D scans of ancient statuary from Egypt, Greece and Rome, a Bronze Age bracelet and two of the Lewis chessman (one king, one queen).