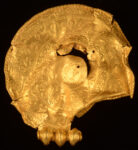

The excavation of one of the six newly-discovered sacrificial pits at the Sanxingdui Bronze Age archaeological site in southwest China’s Sichuan Province has unearthed a bronze sacred tree from the Shu culture, ca. 12th/11th century B.C. It was found in parts in Pit 3, and is so complex that its surviving branches, flowers, some of the trunk and solar wheel ornament took four months to fully excavate because they were buried under heavy layers of ivory and other artifacts.

The excavation of one of the six newly-discovered sacrificial pits at the Sanxingdui Bronze Age archaeological site in southwest China’s Sichuan Province has unearthed a bronze sacred tree from the Shu culture, ca. 12th/11th century B.C. It was found in parts in Pit 3, and is so complex that its surviving branches, flowers, some of the trunk and solar wheel ornament took four months to fully excavate because they were buried under heavy layers of ivory and other artifacts.

Sacred trees have been found before at the site. The 1986 excavation of Pit 2 unearthed hundreds of pieces from six to eight bronze trees, most of them modest in size. Only three of them could be pieced back together from their component parts. One of them, a colossal example that took conservators a decade to reassemble, is now on display as the centerpiece of the Sanxingdui Museum‘s exceptional collection of artifacts from the ancient site.

The massive restored tree consists of a three-legged base with a trunk growing out of it. The trunk is divided into three levels with three branches curling downward in each level. Flowers bloom on the high points of all nine of the branches and birds alight on the flowers. Each branch in turn branches off into three fruit-bearing branchlets, for a total of 27 fruits on the tree. A slim dragon with a horned head undulates down the lower segment of the trunk, his foot planted in the base.

The massive restored tree consists of a three-legged base with a trunk growing out of it. The trunk is divided into three levels with three branches curling downward in each level. Flowers bloom on the high points of all nine of the branches and birds alight on the flowers. Each branch in turn branches off into three fruit-bearing branchlets, for a total of 27 fruits on the tree. A slim dragon with a horned head undulates down the lower segment of the trunk, his foot planted in the base.

There is very little concrete information about the Shu people and state as no written records have survived. The archaeological record and later chroniclers indicate the Shu religion was centered on sun worship, and the bronze trees may have been part of it. The Shu Legend of the Ten Suns held that birds carried nine suns on their backs, flying in the morning from a sacred tree in the East, and landing at night in a sacred tree in the West. Humans, according to the legend, only the saw the birds, not the suns they carried, so they lived their lives blithely unaware there were any other suns besides the one we know.

According to Xu [Feihong, excavation leader], the new one is similar to the No. 2 bronze tree which took archaeologists over a decade to restore. Yet, it’s still not complete with several parts missing.

“It cannot be ruled out that these two might belong to the same tree. If the two sacred trees in pits No. 2 and No. 3 are put together, they can explain a lot of academic issues,” said Xu.

There are no plans as of yet to embark on the reassembly and restoration of the Pit 3 tree, not until all six of the new sacrificial pits have been fully excavated. Armed with all the information and contents of the pits, archaeologists will then piece together this tree too, and it will go on display next to its brother from Pit 2.

There are no plans as of yet to embark on the reassembly and restoration of the Pit 3 tree, not until all six of the new sacrificial pits have been fully excavated. Armed with all the information and contents of the pits, archaeologists will then piece together this tree too, and it will go on display next to its brother from Pit 2.