The Royal Academy of Arts in London is putting on an exhibit of French and Russian modern masters. Hugely famous pieces that were kept hidden under Soviet rule are finally getting to leave the country for the first time since Lenin called art an appendix soon to be cut out.

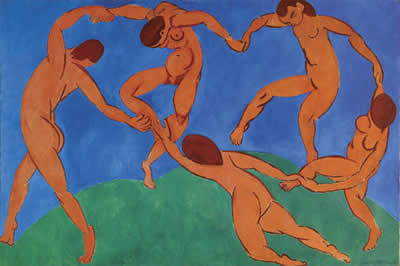

For the first time in history, Russia’s four great state museums, the Hermitage, the Russian, the Pushkin and the Tretiakov Gallery, are joining forces to mount this blockbuster in the West. Long starved of funding, the museums badly need the cash, and the energy-industry giant Eon has sponsored the exhibition. The result is that over 150 paintings, half of them never seen before in Britain, will go on view at the RA when From Russia: French and Russian Master Paintings 1870–1925 opens later this month. Some of the greatest works by Renoir, Cézanne and Van Gogh will hang alongside those by Russia’s greatest modern artists, Chagall, Kandinsky and Malevich.

The exhibit promises to be fascinating because of the history it will reveal about the wealthy (pre-revolution) Russians who collected these wondrous pieces, Ivan Morosov and Sergei Shchukin. They went from living in palaces surrounded by Matisses, Picassos and Van Goghs, to living in shacks and guiding visitors through their former riches, to fleeing the country and dying forlorn.

That same year his private collection was nationalised too, his house later becoming part of the State Museum of Modern Western Art. For a while, Shchukin swallowed his pride, moving into the caretaker’s lodge and acting as guide and curator. But in the summer of 1918 he fled Moscow with a train ticket to Kiev, a false passport and a doll stuffed with diamonds.

Morosov, meanwhile, whose 300-strong collection of Monets, Bonnards, Gauguins and Cézannes had also been seized, was forced to work as deputy keeper of his collection, taking the proles around his beloved pictures. But when he received orders to move into the basement, he fled with his wife and children to Switzerland. He died three years later at the age of 50, no doubt broken by the loss of his homeland and his collection.

Read more about these great collectors in the Royal Academy’s magazine. Read more about the exhibit on the RA’s website.

It runs from January 25 to April 18. I shall browbeat my London stringer (that’s you, Leesifer, just in case you don’t know yet) to go and write us a review.