Archaeologists excavating a Croatian cave overlooking the Adriatic Sea have discovered what they believe is the oldest astrologer’s board ever found. They were digging at the entrance to the cave in 1999 when one of the researchers’ girlfriends burrowed her way through debris into the cavern. She discovered a 33-foot-long passageway leading to a chamber that had been sealed off in antiquity, probably in the first century B.C. during a war against invading Romans. Inside were thousands of pieces of pottery, ivory, and bones around a stalagmite shaped like a phallus.

Archaeologists excavating a Croatian cave overlooking the Adriatic Sea have discovered what they believe is the oldest astrologer’s board ever found. They were digging at the entrance to the cave in 1999 when one of the researchers’ girlfriends burrowed her way through debris into the cavern. She discovered a 33-foot-long passageway leading to a chamber that had been sealed off in antiquity, probably in the first century B.C. during a war against invading Romans. Inside were thousands of pieces of pottery, ivory, and bones around a stalagmite shaped like a phallus.

It took several seasons to excavate the cave. The floor of the cave and all the artifacts were caked in thick, sticky cave clay making them a challenge to dig out and to clean. Once excavated, researchers spent years piecing together the fragments of what turned out to be high quality Hellenistic drinking vessels from the 3rd and 2nd century B.C. The tiny fragments of ivory turned out to be pieces of a Greco-Roman astrology board, beautifully carved with the signs of the zodiac.

It took several seasons to excavate the cave. The floor of the cave and all the artifacts were caked in thick, sticky cave clay making them a challenge to dig out and to clean. Once excavated, researchers spent years piecing together the fragments of what turned out to be high quality Hellenistic drinking vessels from the 3rd and 2nd century B.C. The tiny fragments of ivory turned out to be pieces of a Greco-Roman astrology board, beautifully carved with the signs of the zodiac.

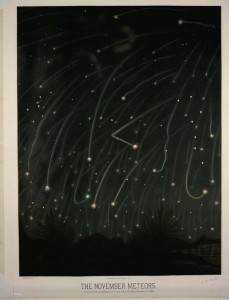

Radiocarbon dating of the ivory indicates the ivory is 2,200 years old, which is just around the time that astrology, originally a Babylonian discipline, became popular under the reign of the Ptolemys in Egypt. It’s the Greco-Egyptian version of astrology that established itself in Europe and that is still in popular use today.

An ancient astrologer, trying to determine a person’s horoscope, could have used the board to show the position of the planets, sun and moon at the time the person was born.

“What he would show the client would be where each planet is, where the sun is, where the moon is and what are the points on the zodiac that were rising and setting on the horizon at the moment of birth,” said Alexander Jones, a professor at the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World at New York University.

“This is probably older than any other known example,” Jones said. “It’s also older than any of the written-down horoscopes that we have from the Greco-Roman world,” he said, adding, “we have a lot of horoscopes that are written down as a kind of document on papyrus or on a wall but none of them as old as this.”

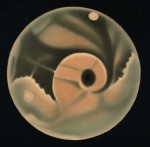

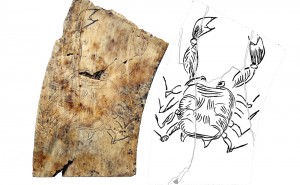

We can’t trace where the ivory came from, but Egypt is certainly a viable candidate. Ivory was a precious material, so once harvested from its elephantine owner it could have been hoarded for years, maybe as long as a century, before it was carved. The board was made by carving ivory plaques in a 28-degree arc with a sign of the zodiac on the face. The plaques were then attached to a flat surface, probably a wood board.

We can’t trace where the ivory came from, but Egypt is certainly a viable candidate. Ivory was a precious material, so once harvested from its elephantine owner it could have been hoarded for years, maybe as long as a century, before it was carved. The board was made by carving ivory plaques in a 28-degree arc with a sign of the zodiac on the face. The plaques were then attached to a flat surface, probably a wood board.

The Cancer plaque is the most complete one, with Gemini and Pisces also clearly identifiable. A partially reconstructed plaque shows the back of an animal that could be Sagittarius’ horse’s ass. The rest of the plaques are too fragmentary to identify.

The Cancer plaque is the most complete one, with Gemini and Pisces also clearly identifiable. A partially reconstructed plaque shows the back of an animal that could be Sagittarius’ horse’s ass. The rest of the plaques are too fragmentary to identify.

Researchers aren’t sure how and why these valuable Hellenistic artifacts found themselves smashed around a stalagmite in an Illyrian cave. The location, overlooking the Adriatic, was a well-traveled commercial route. Illyrians, who the Greeks thought of as somewhat barbarous, could have traded for the goods or pirated them and then brought them to the cave for religious purposes.

Researchers aren’t sure how and why these valuable Hellenistic artifacts found themselves smashed around a stalagmite in an Illyrian cave. The location, overlooking the Adriatic, was a well-traveled commercial route. Illyrians, who the Greeks thought of as somewhat barbarous, could have traded for the goods or pirated them and then brought them to the cave for religious purposes.

According to Stašo Forenbaher, a researcher with the Institute for Anthropological Research in Zagreb whose former girlfriend (now wife) tunneled her way into the sealed-off chamber in 1999, the broken artifacts around the stalagmite suggest the chamber was a sacred space which the locals used to sacrifice to a deity.

“There is definitely a possibility that this astrologer’s board showed up as an offering together with other special things that were either bought or plundered from a passing ship,” Forenbaher said. He pointed out that the drinking vessels found in the cave were carefully chosen. They were foreign-made, and only a few examples of cruder amphora storage vessels were found with them.

“It almost seems that somebody was bringing out wine there, pouring it and then tossing the amphora away because they [the amphora] were not good enough for the gods, they were not good enough to be deposited in the sanctuary,” Forenbaher said.

The Illyrians might not even have known what the astrologer’s board was for, but recognizing it as a valuable and beautiful object they sacrificed it anyway.