On April 2nd, 2013, a crew of poorly-paid professionals and volunteers will begin construction near Messkirch, southwestern Germany, of a medieval monastery town using only materials and techniques from the 9th century. That means masons carving stone blocks by hand while blacksmiths forge and sharpen their tools, and it also means no raincoats, authentic period foods cooked as they were 1200 years ago to sustain workers and visitors alike, and teams of oxen carting materials to the work site instead of trucks.

On April 2nd, 2013, a crew of poorly-paid professionals and volunteers will begin construction near Messkirch, southwestern Germany, of a medieval monastery town using only materials and techniques from the 9th century. That means masons carving stone blocks by hand while blacksmiths forge and sharpen their tools, and it also means no raincoats, authentic period foods cooked as they were 1200 years ago to sustain workers and visitors alike, and teams of oxen carting materials to the work site instead of trucks.

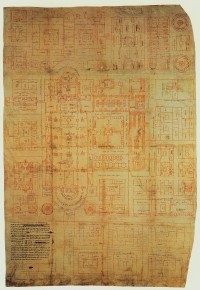

The project is the brainchild of 62-year-old building contractor Bert Geurten, and it’s a dream he’s nurtured since he was 15 years old. In 1965, he saw a scale model of the Plan of Saint Gall, a detailed 9th century architectural drawing of a monastic compound, at the Age of Charlemagne exhibition in Bert (and Charlemagne’s) hometown of Aachen, Germany. It was the first scale model of the Plan ever made — but far from the last; it started a trend — and it ignited young Bert’s imagination so thoroughly that 45 years later he’s making it come to life.

The Plan of St. Gall (so named because the designer, Abbot Haito of Reichenau, dedicated it to Gozbert, Abbot of the Abbey of St. Gall in Switzerland from 816 to 836) is a scale map of a complete Benedictine monastic compound. There’s the monastery itself, of course, but also churches, houses, stables, kitchens, an infirmary, workshops, every component necessary for a successful monastic society and its lay satellites. It is the only surviving architectural drawing between the fall of Rome and the 13th century.

The Plan of St. Gall (so named because the designer, Abbot Haito of Reichenau, dedicated it to Gozbert, Abbot of the Abbey of St. Gall in Switzerland from 816 to 836) is a scale map of a complete Benedictine monastic compound. There’s the monastery itself, of course, but also churches, houses, stables, kitchens, an infirmary, workshops, every component necessary for a successful monastic society and its lay satellites. It is the only surviving architectural drawing between the fall of Rome and the 13th century.

The Carolingian monastery project has some initial funding from local and EU sources, but the $1.3 million they have in the bank is expected to last just a few years. Since the estimated end-date of the project is 2050, fund-raising is going to be a constant issue. Bert Geurten hopes it will be at least partially sustained by visitors coming to see the construction. Meanwhile, he’s pinching pennies and people are so excited about the idea that he has an embarrassment of applications to go through.

Given the tight budget, craftsmen salaries will remain low. “The net wage is about €1,200 (per month),” says Geurten. “I can’t pay more.” The working hours are also a long way from what German trade unions recommend these days. They will work from April 2 — Charlemagne’s birthday — almost without break until St. Martin’s Day, on Nov. 11. During those eight months, there will be one single weekend off. “In the Middle Ages, the rent for the year was always paid on St. Martin’s Day,” said Geurten. The winter break lasts until April when the temperatures are warm enough to work again.

Despite the difficult conditions, the project has been swamped with applications. “I’ve had 85 stone masons apply already,” says Geurten. “They all dream of having the chance to work with their hands.” This also applies to the blacksmith. “They won’t be hammering kitschy horseshoes for tourists. The forge must supply the site with tools,” he adds.

Overall, the construction site will have 20 to 30 permanent staff in addition to volunteers. There has already been a lot of interest. “From Lufthansa pilots to a teacher, all kinds of people have applied.” One candidate even sent his application written in medieval German on a real roll of parchment. Meanwhile, schools will likely be allowed to join in with the site’s work for as long as a week. “We are developing a plan that will enable the children to prepare for their experience in the classroom first,” says Geurten.

I hope they hire that guy who wrote his application in medieval German.

The interest from volunteers bodes well that there will be ongoing interest from paying visitors for the 40 years it’ll take to build this sucker. That has certainly been the case for Guédelon, a castle being built today in Burgundy according to the architectural principles of the ideal military fortress laid down by King Philip Augustus of France in the late 12th, early 13th centuries, using solely the techniques and materials available to workers in the 13th century. Construction has been going along merrily since 1997 and each year, hundreds of thousands of people go to Guédelon. Many of them are repeat customers who want to compare the progress of construction from year to year.

It doesn’t always go that well, though. Ozark Medieval Fortress, a castle modeled on the Guédelon project that has far more modest ambitions than the huge monastery project, unfortunately ran into financial difficulties. Work stopped in November and earlier this month the board voted to list the property and its castle stump for sale for $500,000.