The Library of Congress’ online collections of historical images are some of my favorite time sinks. I found a new one this weekend that sucked up hours of browsing time and more hours of researching random tidbits discovered during the browse. It’s the Performing Arts Posters collection, 2114 publicity posters from live entertainment of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Most of them are color lithographs or woodcuts that advertise all kinds of performances, from magic shows to splashy theatrical reenactments of historical events to operas.

The Library of Congress’ online collections of historical images are some of my favorite time sinks. I found a new one this weekend that sucked up hours of browsing time and more hours of researching random tidbits discovered during the browse. It’s the Performing Arts Posters collection, 2114 publicity posters from live entertainment of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Most of them are color lithographs or woodcuts that advertise all kinds of performances, from magic shows to splashy theatrical reenactments of historical events to operas.

If you have time to burn, I recommend you view all and arrow through the entire collection in alphabetical order. If you do not have eternities to while away, you could browse the three main collections that make up the whole: the Magic Poster Collection, the Minstrel Poster Collection, and the Theatrical Poster Collection, the last of which is subdivided according to genre (Burlesque, Specialty Acts, Vaudeville, etc.).

If you have time to burn, I recommend you view all and arrow through the entire collection in alphabetical order. If you do not have eternities to while away, you could browse the three main collections that make up the whole: the Magic Poster Collection, the Minstrel Poster Collection, and the Theatrical Poster Collection, the last of which is subdivided according to genre (Burlesque, Specialty Acts, Vaudeville, etc.).

The Magic Poster Collection includes some prestidigitation masters who are still famous today, like Harry Houdini and Howard Thurston, but I have a soft spot for the more obscure acts. Sometimes it’s the little guy who has the best graphics. The Minstrel Poster Collection is, as the name suggests, chock full o’ racist caricatures. Those shows were popular for an incredibly long time. The oldest poster in the collection dates to 1847, the pre-Civil War heyday of white actors blackening their faces with burnt cork and acting like buffoons.

The Magic Poster Collection includes some prestidigitation masters who are still famous today, like Harry Houdini and Howard Thurston, but I have a soft spot for the more obscure acts. Sometimes it’s the little guy who has the best graphics. The Minstrel Poster Collection is, as the name suggests, chock full o’ racist caricatures. Those shows were popular for an incredibly long time. The oldest poster in the collection dates to 1847, the pre-Civil War heyday of white actors blackening their faces with burnt cork and acting like buffoons.

The troupe advertised in the poster, the New Orleans Ethiopian Serenaders (also known as Buckley’s Serenaders after troupe leader James Buckley), were touring England at the time where they were a notable success. Contrary to the standard song and dance style of minstrel shows, the New Orleans Ethiopian Serenaders’ 1847 performance at London’s Princess Theater kicked off with a burlesque version of the opera La Sonnambula by Vincenzo Bellini. This became something of a trademark for Buckley’s shows even when they returned to the United States and set up permanent shop in a theater on Broadway until it closed in 1862.

The troupe advertised in the poster, the New Orleans Ethiopian Serenaders (also known as Buckley’s Serenaders after troupe leader James Buckley), were touring England at the time where they were a notable success. Contrary to the standard song and dance style of minstrel shows, the New Orleans Ethiopian Serenaders’ 1847 performance at London’s Princess Theater kicked off with a burlesque version of the opera La Sonnambula by Vincenzo Bellini. This became something of a trademark for Buckley’s shows even when they returned to the United States and set up permanent shop in a theater on Broadway until it closed in 1862.

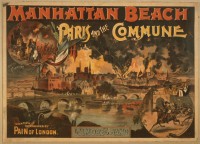

The Theatrical Poster Collection has the lion’s share of art works, over 1800 posters covering multiple genres of variety stage theater. Of course the Burlesque posters are good unclean fun, but some of the most spectacular graphics come from the Operetta category, especially the D’Oyly Carte’s Gilbert and Sullivan productions, and from the Kiralfy Brothers, a company that staged lavish spectaculars of Biblical stories, famous adventure stories, and quasi-historical re-enactments.

The Theatrical Poster Collection has the lion’s share of art works, over 1800 posters covering multiple genres of variety stage theater. Of course the Burlesque posters are good unclean fun, but some of the most spectacular graphics come from the Operetta category, especially the D’Oyly Carte’s Gilbert and Sullivan productions, and from the Kiralfy Brothers, a company that staged lavish spectaculars of Biblical stories, famous adventure stories, and quasi-historical re-enactments.

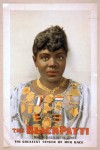

Here’s an interesting link that cropped up. Three of the posters in the Vaudeville category advertise a female impersonator known as Stuart, the Male Patti (1, 2, 3). I assumed Patti was another vaudeville performer of the wearing-little-more-than-a-corset-on-stage variety, but then in the Portrait Posters, posters advertising a single star performer, I came across one M. Sissieretta Jones, the Black Patti, “the greatest singer of her race.”

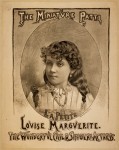

Here’s an interesting link that cropped up. Three of the posters in the Vaudeville category advertise a female impersonator known as Stuart, the Male Patti (1, 2, 3). I assumed Patti was another vaudeville performer of the wearing-little-more-than-a-corset-on-stage variety, but then in the Portrait Posters, posters advertising a single star performer, I came across one M. Sissieretta Jones, the Black Patti, “the greatest singer of her race.”  A page later and what to my wondering eyes should appear but “the wonderful child singer & actress” Louise Marguerite, aka the Miniature Patti, who I think bears a striking resemblance to a Scarlett Johansson ca. The Horse Whisperer.

A page later and what to my wondering eyes should appear but “the wonderful child singer & actress” Louise Marguerite, aka the Miniature Patti, who I think bears a striking resemblance to a Scarlett Johansson ca. The Horse Whisperer.

I discovered that Patti was not a Vaudeville performer, but rather a famous Italian coloratura soprano called Adelina Patti. She was something of a prodigy, debuting as Lucia in Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor in 1859 when she was just 16 years old.  Two years later, she was invited to perform at Covent Garden in a non-burlesque version of La Sonnambula and was a smash hit. She continued to be a smash for decades, even though her voice changed and deepened as she aged. Verdi adored her, calling her the greatest singer who ever lived. In 1862, she performed the popular song “Home, Sweet Home” at the White House for President Abraham Lincoln and First Lady Mary Todd. They were moved to tears and asked her to sing it again. After that, the song became a signature piece for her.

Two years later, she was invited to perform at Covent Garden in a non-burlesque version of La Sonnambula and was a smash hit. She continued to be a smash for decades, even though her voice changed and deepened as she aged. Verdi adored her, calling her the greatest singer who ever lived. In 1862, she performed the popular song “Home, Sweet Home” at the White House for President Abraham Lincoln and First Lady Mary Todd. They were moved to tears and asked her to sing it again. After that, the song became a signature piece for her.

By the time of the male (1898), Black (1899) and child (1894) Pattis, the original Patti was in her 50s singing at her mature peak, making thousands of dollars a night which she insisted be paid to her in gold before every performance. She retired from public performance in the early 1900s, but still put on the occasional private or charity concert. Her bags of gold and smart investments ensured that her retirement was a luxurious one. She died in 1919 and is buried at Paris’ Père Lachaise Cemetery.

I very much doubt the other Pattis were so fortunate. I couldn’t find out what happened to Stuart and Louise Marguerite, but Matilda Sissieretta Joyner Jones was a pioneer and a trailblazer. She’s probably the only one of the three who came by her moniker legitimately, since it was Adelina Patti’s manager who saw her perform in 1888 and suggested she take her soprano virtuosity on tour. In 1892 she was the first African American to sing at New York’s Music Hall (renamed Carnegie Hall a year later). That same year she sang at the White House for President Benjamin Harrison. She would sing for the next three presidents after him — Grover Cleveland, William McKinley, Theodore Roosevelt — and for the British royal family.

I very much doubt the other Pattis were so fortunate. I couldn’t find out what happened to Stuart and Louise Marguerite, but Matilda Sissieretta Joyner Jones was a pioneer and a trailblazer. She’s probably the only one of the three who came by her moniker legitimately, since it was Adelina Patti’s manager who saw her perform in 1888 and suggested she take her soprano virtuosity on tour. In 1892 she was the first African American to sing at New York’s Music Hall (renamed Carnegie Hall a year later). That same year she sang at the White House for President Benjamin Harrison. She would sing for the next three presidents after him — Grover Cleveland, William McKinley, Theodore Roosevelt — and for the British royal family.

Despite her success as a soprano in Europe and the United States, she soon hit the segregation ceiling. When she found that the major opera houses like the Metropolitan would not hire a black artist, she formed a troupe of her own, the Black Patti Troubadours, and went on the road with a musical review that included vaudeville and minstrel acts as well as greatest hits of opera, not just arias but fully staged scenes. The troupe was a success for two decades and earned her a great deal of money.

She retired in 1915 at the age of 46 due to illness and to care for her sick mother in Providence, Rhode Island. The money she had made sadly did not last. Eventually she had to sell all her properties, her awards, and her trophies just to pay the bills. She was 74 and penniless when she died of cancer in 1933.