Alfons Mucha, the Czech artist who basically invented Art Nouveau (it was originally known as “Mucha Style”) and whose characteristic berobed women with flowing hair against a field of flowers have been selling everything from theatrical productions to champagne to chocolate since the late 19th century, rejected the Art Nouveau label, considering himself and his art first and foremost a product of the Slavic folk tradition in which he was raised. In 1900, he traveled all over the Balkans in preparation for his work on the Bosnia-Herzegovina pavilion for the Paris World’s Fair. Although he returned to Paris and continued his customary work, he was inspired by the trip to dedicate himself to “work for the [Czech] nation.”

Alfons Mucha, the Czech artist who basically invented Art Nouveau (it was originally known as “Mucha Style”) and whose characteristic berobed women with flowing hair against a field of flowers have been selling everything from theatrical productions to champagne to chocolate since the late 19th century, rejected the Art Nouveau label, considering himself and his art first and foremost a product of the Slavic folk tradition in which he was raised. In 1900, he traveled all over the Balkans in preparation for his work on the Bosnia-Herzegovina pavilion for the Paris World’s Fair. Although he returned to Paris and continued his customary work, he was inspired by the trip to dedicate himself to “work for the [Czech] nation.”

Mucha was born in 1860 in Ivancice, a rural community in Moravia that was then part of the Austrian Empire. The area was a hotbed of Slavic nationalism, even more so in reaction to the Habsburg efforts to “Germanize” the many cultures in the empire. He left in 1879 to do design work for a theater in Vienna. He returned to Moravia after the theater burned down, doing some freelance art work including murals for Count Karl Khuen of Mikulov who would fund his first formal artistic education.

In 1887 he moved to Paris, studying and getting jobs as a commercial artist. He became famous in 1895 after a chance encounter in a print shop resulted in his making a poster for the play Gismonda, starring the incomparable Sarah Bernhardt. She loved the poster so much that she signed him to a six-year contract.

In 1887 he moved to Paris, studying and getting jobs as a commercial artist. He became famous in 1895 after a chance encounter in a print shop resulted in his making a poster for the play Gismonda, starring the incomparable Sarah Bernhardt. She loved the poster so much that she signed him to a six-year contract.

His fame spread worldwide, but back in his homeland he was considered something of a sell-out, more French than Slav. Although Mucha saw himself as Czech and his art as an expression of his Slavic identity, his countrymen tended to disagree. When he was commissioned to paint murals in the Mayor’s Office at the New Municipal House in Prague in 1909, the move was roundly criticized by the public.

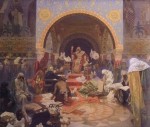

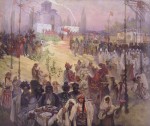

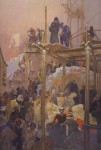

Undeterred, in 1910 Mucha moved his family to Prague and, while still taking some commercial gigs to pay the bills, poured his talents and resources into the passion project of a lifetime: a series of 20 monumental paintings (the biggest canvas is 26 feet wide and 20 feet tall) depicting the history of the Slavic people.

Undeterred, in 1910 Mucha moved his family to Prague and, while still taking some commercial gigs to pay the bills, poured his talents and resources into the passion project of a lifetime: a series of 20 monumental paintings (the biggest canvas is 26 feet wide and 20 feet tall) depicting the history of the Slavic people.  The Slav Epic took him 18 years to complete, during which time World War I saw the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the creation of the new nation of Czechoslovakia with Prague as its capital.

The Slav Epic took him 18 years to complete, during which time World War I saw the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the creation of the new nation of Czechoslovakia with Prague as its capital.

On September 1, 1928, Alfons Mucha donated the complete Slav Epic to the people of Czechoslovakia.  All 20 paintings went on display in the Trade Fair Palace in Prague where they inspired a range of reactions, many of them negative. The left-wing nationalists considered the style and pan-Slavic sentiments old-fashioned, and the fascists held Slavic nationalism itself in contempt.

All 20 paintings went on display in the Trade Fair Palace in Prague where they inspired a range of reactions, many of them negative. The left-wing nationalists considered the style and pan-Slavic sentiments old-fashioned, and the fascists held Slavic nationalism itself in contempt.

When in 1939 Nazi Germany followed its occupation of the Sudetenland by invading the rest of Czechoslovakia, Mucha was one of the first artists to be arrested by the Gestapo. They released him, but he died shortly thereafter on July 14, 1939 of pneumonia.

When in 1939 Nazi Germany followed its occupation of the Sudetenland by invading the rest of Czechoslovakia, Mucha was one of the first artists to be arrested by the Gestapo. They released him, but he died shortly thereafter on July 14, 1939 of pneumonia.  In his will, he bequeathed the Slav Epic to the city of Prague, on condition that they build a special pavilion to house them.

In his will, he bequeathed the Slav Epic to the city of Prague, on condition that they build a special pavilion to house them.

Building a pavilion for enormous Slav nationalist paintings wasn’t Prague’s top concern during World War II.  Just keeping the paintings out of Nazi hands was challenge enough. The Slav Epic was rolled up and hidden in storage rooms (as well as, rumor has it, a crypt) to keep it safe. Unfortunately the end of the war wasn’t much help, as the Soviet-backed Communist Party which took power in the 1948 Czech coup had no love for the Epic. They certainly weren’t going to build a pavilion for it.

Just keeping the paintings out of Nazi hands was challenge enough. The Slav Epic was rolled up and hidden in storage rooms (as well as, rumor has it, a crypt) to keep it safe. Unfortunately the end of the war wasn’t much help, as the Soviet-backed Communist Party which took power in the 1948 Czech coup had no love for the Epic. They certainly weren’t going to build a pavilion for it.

The paintings were moved to the southern Moravian town of Moravský Krumlov in 1950 for safekeeping but remained in storage. Finally in 1963 they went on display at the local castle. When the Communist regime fell in 1989, there was discussion about bringing the paintings back to Prague, since the artist did give them to the city, but the Moravský Krumlov community vehemently protested. The Mucha family sided with Moravský Krumlov, noting that legally Prague couldn’t claim the paintings without complying with the condition in Alfons’ will requiring a dedicated pavilion.

The paintings were moved to the southern Moravian town of Moravský Krumlov in 1950 for safekeeping but remained in storage. Finally in 1963 they went on display at the local castle. When the Communist regime fell in 1989, there was discussion about bringing the paintings back to Prague, since the artist did give them to the city, but the Moravský Krumlov community vehemently protested. The Mucha family sided with Moravský Krumlov, noting that legally Prague couldn’t claim the paintings without complying with the condition in Alfons’ will requiring a dedicated pavilion.  They were concerned that moving the works only to put them up in some transitional space would be detrimental to their delicate health.

They were concerned that moving the works only to put them up in some transitional space would be detrimental to their delicate health.

A decade of legal wrangling ensued, in the middle of which Prague approved plans for the construction of a new pavilion which was scheduled to be complete by 2010.  Disputes over the proposed architecture of the pavilion kept it from ever getting built, but come 2010, Prague sent movers to the Moravský Krumlov castle anyway.

Disputes over the proposed architecture of the pavilion kept it from ever getting built, but come 2010, Prague sent movers to the Moravský Krumlov castle anyway.

The Mucha family got an injunction to stop the move until they’ve built this everlovin’ pavilion like they’re supposed to, but five of the paintings made it out the door anyway, going on display in early 2011 at Prague’s Veletrzni Palace after restorers examined them. A year has passed and the legal issues remain unresolved, but over the protests of the Mucha family and the town of Moravský Krumlov, now Prague has taken the remaining 15 works.

The Veletrzni Palace is the only place with the wall space to display all 20 gigantic paintings, but its conditions are far from ideal. Temperature and humidity levels fluctuate enormously with the weather, and again, a temporary exhibit in an old building does not comply with the conditions stipulated by Alfons Mucha.

The Veletrzni Palace is the only place with the wall space to display all 20 gigantic paintings, but its conditions are far from ideal. Temperature and humidity levels fluctuate enormously with the weather, and again, a temporary exhibit in an old building does not comply with the conditions stipulated by Alfons Mucha.  The Mucha family and the foundation they run are working assiduously to create a permanent location for the Slav Epic in Prague’s central train station.

The Mucha family and the foundation they run are working assiduously to create a permanent location for the Slav Epic in Prague’s central train station.

The Mucha Foundation says that Prague’s main railway station is the best permanent home for the paintings. [The artist’s grandson] John Mucha says that the foundation is in negotiations with the council about the plans. “Everyone’s pulling in the same direction,” he says. “If we all manage to keep this momentum, the Slav Epic should be unveiled [there] in spring 2014.” When describing the suitability of the venue, John Mucha says that the train noise can be screened, and appropriately the art nouveau station was designed by Josef Fanta, a friend of Alphonse Mucha.

We’ll see if that ever happens. Meanwhile, the Epic will have to make do with the drafty, moist palace.