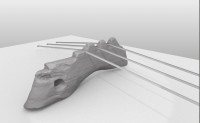

Archaeologists excavating the High Pasture Cave on the Isle of Skye have discovered a wooden fragment that they believe came from a lyre or similar stringed instrument. The fragment was burned and part of it broken off, but you can clearly see the carved string notches that identify it as a bridge. It was discovered in the rake-out deposits of the hearth outside the entrance to the cave. The deposits date to between 550 and 450 B.C., which would make the bridge a fragment of the oldest stringed instrument found in Europe.

Archaeologists excavating the High Pasture Cave on the Isle of Skye have discovered a wooden fragment that they believe came from a lyre or similar stringed instrument. The fragment was burned and part of it broken off, but you can clearly see the carved string notches that identify it as a bridge. It was discovered in the rake-out deposits of the hearth outside the entrance to the cave. The deposits date to between 550 and 450 B.C., which would make the bridge a fragment of the oldest stringed instrument found in Europe.

Artifacts and organic remains ranging from the Bronze to the Iron Age have been found in the High Pasture Cave. The large cave complex appears to have been put to a variety of uses over hundreds of years, including religious rituals. In 2006, archaeologists discovered a cache of antler and bone points dating to 500 B.C. in a section of the cave known as the Bone Passage. Seven of the pieces had an odd wear pattern at the tip suggesting they had been turned over and over again. Experts speculated at the time that they could have been used as tuning pegs for a lyre. Now they’ve found evidence of an actual lyre from the same period in the cave, so the speculation looks considerably more solid.

(Not that they’re a matched set or anything. They were found in different spots and reconstructions of the bridge suggest it came from a six-stringed instrument which would only need six tuning pegs.)

(Not that they’re a matched set or anything. They were found in different spots and reconstructions of the bridge suggest it came from a six-stringed instrument which would only need six tuning pegs.)

The oldest stringed instruments in the archaeological record have been found in what is now Iraq, like the bull-headed lyre found in the Royal Cemetery of Ur which dates to around 2500 B.C. Because stringed instruments are typically made out of wood, they usually rot before archaeologists can find them; in fact the sound box of the Ur lyre had rotted away, but the bitumen-covered front panel and the gold and lapis lazuli bearded bull’s head survived.

Musical instruments from Iron Age Europe were not the luxury models of ancient Sumer nor did they have the advantage of a dry, hot environment to preserve the wood. Even Roman-era instruments are so hard to come by that we have to rely on literature, mosaics and frescoes to learn about them, or carvings on altars like the one unearthed in Musselburgh in 2010 which until now was the earliest representation of a musical instrument ever found in Scotland. Finding a piece of an instrument that is centuries older than any previous discoveries and is so clearly recognizable as a piece of an instrument (the bridge is probably the single most recognizable part of a lyre because of its shape and the string notches) is therefore enormously significant to our understanding of ancient music and poetry in Europe.

Culture and External Affairs Secretary Fiona Hyslop added: “This is an incredible find and it clearly demonstrates how our ancestors were using music and ritual in their lives. The evidence shows that Skye was a gathering place over generations and that it obviously had an important role to play in the celebration and ritual of life more than 2,000 years ago.”

The artifact is being conserved by AOC Archaeology in Edinburgh. There are some nice views and models of the bridge in the following video, and a charming finale in which Dr. Graeme Lawson of Cambridge Music – Archaeological Research plays a reproduction ancient lyre.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DFCvu0oKlvU&w=430]