After years of conservation to preserve organic remains, artifacts from the wreck of the 19th century Hawaiian royal yacht the Ha’aheo o Hawai’i have returned to Hawaii. They will become part of the permanent collection of the Kaua’i Museum where they will go on display close to where they spent almost two centuries under the turquoise ocean.

The yacht started out its life in far less congenial waters. Captain George Crowninshield, scion of the prominent Boston Brahmin seafaring family, commissioned Salem’s greatest shipwright Retire Becket to build him the first ocean-going pleasure yacht in the country. Crowninshield was involved in every aspect of construction and he spared no expense. The ship cost $50,000 to build, plus another $50,000 was spent on the furniture and finishes like flamed mahogany and birds-eye maple paneling, custom furniture by Boston’s premier cabinetmaker Thomas Seymour, silk velvet upholstery with gold lace trim, ormulu chandeliers, bespoke sets of silver, porcelain, glass and linens. It even had indoor plumbing. Cleopatra’s Barge, an 83-foot brigantine, was launched on October 21st, 1816. Inclement winter prevented her from sailing right away and the vessel was instantly famous so when the ship was frozen at the dock after a short trial run in December, it was opened up to visitors. Thousands came to see it.

The yacht started out its life in far less congenial waters. Captain George Crowninshield, scion of the prominent Boston Brahmin seafaring family, commissioned Salem’s greatest shipwright Retire Becket to build him the first ocean-going pleasure yacht in the country. Crowninshield was involved in every aspect of construction and he spared no expense. The ship cost $50,000 to build, plus another $50,000 was spent on the furniture and finishes like flamed mahogany and birds-eye maple paneling, custom furniture by Boston’s premier cabinetmaker Thomas Seymour, silk velvet upholstery with gold lace trim, ormulu chandeliers, bespoke sets of silver, porcelain, glass and linens. It even had indoor plumbing. Cleopatra’s Barge, an 83-foot brigantine, was launched on October 21st, 1816. Inclement winter prevented her from sailing right away and the vessel was instantly famous so when the ship was frozen at the dock after a short trial run in December, it was opened up to visitors. Thousands came to see it.

When the ice thawed in late March of 1817, George took Cleopatra’s Barge on a long, leisurely Mediterranean cruise. Everywhere he stopped, Crowninshield was greeted by thousands of admirers wanting to get a glimpse of his luxurious ship. One day in Barcelona the yacht had 8,000 visitors. He was also watched by less friendly people: the British and French navies, who put men-of-war on his tail because they had heard the widespread rumor that Captain George was secretly planning on rescuing Napoleon from St. Helena and bringing the ex-emperor home with him to America. Whether this was truly his cockamamie scheme or not, his actions could certainly be seen in a suspicious light. He got 300 letters of introduction to important people on the continent, stopped at Elba where he met Napoleon’s aides who gave him more letters of introduction to the Bonaparte family, visited with the family in Rome — Napoleon’s sister Paulina Bonaparte, Princess Borghese, gave Crowninshield a snuff-box, her sister Princess Murat, Queen of Naples, gave him a ring, Napoleon’s mother gave him a Sevres chocolate mug and her son’s boots — but ultimately went home without an exiled former emperor on board.

When the ice thawed in late March of 1817, George took Cleopatra’s Barge on a long, leisurely Mediterranean cruise. Everywhere he stopped, Crowninshield was greeted by thousands of admirers wanting to get a glimpse of his luxurious ship. One day in Barcelona the yacht had 8,000 visitors. He was also watched by less friendly people: the British and French navies, who put men-of-war on his tail because they had heard the widespread rumor that Captain George was secretly planning on rescuing Napoleon from St. Helena and bringing the ex-emperor home with him to America. Whether this was truly his cockamamie scheme or not, his actions could certainly be seen in a suspicious light. He got 300 letters of introduction to important people on the continent, stopped at Elba where he met Napoleon’s aides who gave him more letters of introduction to the Bonaparte family, visited with the family in Rome — Napoleon’s sister Paulina Bonaparte, Princess Borghese, gave Crowninshield a snuff-box, her sister Princess Murat, Queen of Naples, gave him a ring, Napoleon’s mother gave him a Sevres chocolate mug and her son’s boots — but ultimately went home without an exiled former emperor on board.

Crowninshield and Cleopatra’s Barge returned to Salem on October 3rd, 1817. George stayed on board making an extremely fancy houseboat out of his yacht. He got less than two months’ use of it, sadly, as he died of a heart attack on board on November 26th, 1817. He was 51 years old. His family stripped the elegant furnishings and used it as a trade vessel for a few years before selling it to another mercantile concern. In November of 1820, Cleopatra’s Barge was sold again, this time to King Kamehameha II (aka “Liholiho”) of Hawaii. The King paid 8,000 piculs (1,064,000 pounds) of sandalwood, an estimated value of $80,000, for the ship and thus Cleopatra’s Barge became the first and only royal yacht in any part of what would become the United States.

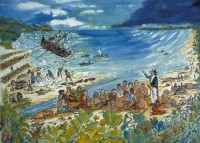

Kamehameha II loved his new toy. He outfitted it in additional finery and cannon for ceremonial shots and traveled the islands with it. The honeymoon period was short-lived, however, as by April 1822 it became clear that so much of the wood was rotting the ship would have to be dry-docked and extensively repaired. Fresh lumber had to be secured from the Pacific Northwest so it was more than a year before the yacht was seaworthy again. The king renamed her Ha’aheo o Hawai’i (Pride of Hawaii) and the rebuilt ship was relaunched on May 10th, 1823.

Kamehameha II loved his new toy. He outfitted it in additional finery and cannon for ceremonial shots and traveled the islands with it. The honeymoon period was short-lived, however, as by April 1822 it became clear that so much of the wood was rotting the ship would have to be dry-docked and extensively repaired. Fresh lumber had to be secured from the Pacific Northwest so it was more than a year before the yacht was seaworthy again. The king renamed her Ha’aheo o Hawai’i (Pride of Hawaii) and the rebuilt ship was relaunched on May 10th, 1823.

Again his enjoyment of the yacht would be short-lived. King Kamehameha II decided to go to London to meet King George IV. Instead of taking the Ha’aheo o Hawai’i, however, he was persuaded to book passage on the whaler L’Aigle because its crew, led by one Captain Valentine Starbuck (no word on his relation to the Battlestar Galactica pilot), was familiar with the route. The king, his wife Queen Kamāmalu and other Hawaiian notables, left for England in November of 1823. After a stop in Brazil, they arrived in Portsmouth on May 17th, 1824, and then hung around for a few weeks waiting for King George to fix a date for the audience. They were finally scheduled to meet on June 21st, but they had to postpone it when the Hawaiian royals were struck with measles. On July 8th, 1824, Queen Kamāmalu died. King Kamehameha II died six days later. Their bodies returned to Hawaii almost a year later, on May 6th, 1825.

His beloved royal yacht would precede King Kamehameha II to the grave. It ran aground on a reef in Hanalei Bay on the north coast of the island of Kauai. It’s unclear what the ship was doing in such a remote location. The Christian missionaries the king had often given rides to on his ship said it was persistent drunkenness of the crew that led to the Ha’aheo o Hawai’i‘s wreck. An attempt was made to rescue the vessel which was still above the waterline, but it failed, snapping the main mast, and when the news reached the islands that the king was dying, whatever parts of it could be salvaged were and then the ship was abandoned to the surf.

His beloved royal yacht would precede King Kamehameha II to the grave. It ran aground on a reef in Hanalei Bay on the north coast of the island of Kauai. It’s unclear what the ship was doing in such a remote location. The Christian missionaries the king had often given rides to on his ship said it was persistent drunkenness of the crew that led to the Ha’aheo o Hawai’i‘s wreck. An attempt was made to rescue the vessel which was still above the waterline, but it failed, snapping the main mast, and when the news reached the islands that the king was dying, whatever parts of it could be salvaged were and then the ship was abandoned to the surf.

The surf did its job well and the wreck of the opulent royal yacht remained unexplored for more than 170 years. In 1994, Paul Forsythe Johnston, Curator of Maritime History at the Smithsonian Institutions’ National Museum of American History and formerly the curator of the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem which has a long history with the yacht from her Cleopatra’s Barge days, applied for and was granted Hawaii’s first underwater archaeological permit to search for the Ha’aheo o Hawai’i. The next year, diver, historian and shipwreck hunter Richard Rogers volunteered his own vessel to help in the search. This video follows the team in the first few weeks of the search:

The surf did its job well and the wreck of the opulent royal yacht remained unexplored for more than 170 years. In 1994, Paul Forsythe Johnston, Curator of Maritime History at the Smithsonian Institutions’ National Museum of American History and formerly the curator of the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem which has a long history with the yacht from her Cleopatra’s Barge days, applied for and was granted Hawaii’s first underwater archaeological permit to search for the Ha’aheo o Hawai’i. The next year, diver, historian and shipwreck hunter Richard Rogers volunteered his own vessel to help in the search. This video follows the team in the first few weeks of the search:

Hanalei Bay Shipwreck from John Yasunaga on Vimeo.

For four weeks each year between 1995 and 2001, the search party looked for the wreck. At first they only found debris, but a couple of seasons in they finally discovered the wreck under 10 feet of water and 10 feet of sand, documented it thoroughly and recovered some of its artifacts.

All told, more than 1,000 artifacts were retrieved.

“We found gold, silver, Hawaiian poi pounders, gemstones, a boat whistle, knives, forks, mica, things from all over the world, high- and low-end European stuff. Every bit of it is royal treasure,” Rogers said. […] His favorite discovery was a trumpet shell.

“I found it under a bunch of sand and carried it onto the deck. This was in 1999. I blew it and it made the most beautiful sound going out over Hanalei Bay,” Rogers recalled. “I thought about how it hadn’t been blown in over 170 years.”

The principal value of the artifacts is historical, said Paul F. Johnston, Ph.D., Curator of Maritime History at the National

Museum of American History Smithsonian Institution. They represent the only known objects from the short but intense reign of Kamehameha II, the man who abolished the Hawaiian kapu (taboo) socio-cultural system and allowed Christian missionaries into the kingdom.

“He only reigned from 1819 -1824, but Old Hawaii changed forever and irrevocably from the changes he put into place during that short period. He was an important member of our nation’s only authentic royalty,” Johnston said.

The Smithsonian has held the artifacts since their discovery for conservation and study, but they belong to the state of Hawaii. The museum has received four crates of objects recovered from the wreck and is expecting another two. Once everything is in place, curators will open the boxes and start unpacking their royal treasure for display.

The Smithsonian has held the artifacts since their discovery for conservation and study, but they belong to the state of Hawaii. The museum has received four crates of objects recovered from the wreck and is expecting another two. Once everything is in place, curators will open the boxes and start unpacking their royal treasure for display.