Dating to around 2600 B.C., the harbor at Wadi al-Jarf on the Red Sea in Egypt is the oldest port complex ever discovered in the world. It was built during the reign of the Pharaoh Snefru (ca. 2620–2580 B.C.), the founder of the 4th Dynasty, and was primarily used for boat travel to the Egypt’s main copper and turquoise mines on the Sinai Peninsula. An L-shaped pier extended east from the shore into the water for 160 meters (525 feet) before turning southeast for 120 meters (394 feet). Its remains are still clearly visible at low tide. The pier created a breakwater and large sheltered area where ships could be moored. This was confirmed when a group of at least 22 limestone ship anchors were found south of the east branch of the pier.

Dating to around 2600 B.C., the harbor at Wadi al-Jarf on the Red Sea in Egypt is the oldest port complex ever discovered in the world. It was built during the reign of the Pharaoh Snefru (ca. 2620–2580 B.C.), the founder of the 4th Dynasty, and was primarily used for boat travel to the Egypt’s main copper and turquoise mines on the Sinai Peninsula. An L-shaped pier extended east from the shore into the water for 160 meters (525 feet) before turning southeast for 120 meters (394 feet). Its remains are still clearly visible at low tide. The pier created a breakwater and large sheltered area where ships could be moored. This was confirmed when a group of at least 22 limestone ship anchors were found south of the east branch of the pier.

Carved into limestone hills next to a water spring, archaeologists found a warehouse system of 30 storage galleries, the largest of which are more than 100 feet long. They average about 10 feet wide and eight feet high. The galleries were used to store boat parts, shipping materials and food and water supplies for the seafaring voyages. They were also used to make repairs on ships. There are pottery kilns nearby and large quantities of pottery believed to have been used as a water containers have been found in the galleries.

Carved into limestone hills next to a water spring, archaeologists found a warehouse system of 30 storage galleries, the largest of which are more than 100 feet long. They average about 10 feet wide and eight feet high. The galleries were used to store boat parts, shipping materials and food and water supplies for the seafaring voyages. They were also used to make repairs on ships. There are pottery kilns nearby and large quantities of pottery believed to have been used as a water containers have been found in the galleries.

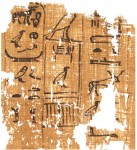

In 2013, archaeologists discovered hundreds of papyrus fragments, some of them more than two feet long. The papyri had been deposited in front of galleries G1 and G2 where large blocking stones were placed to close off the entrance to the galleries. Written in hieratic (simplified hieroglyphics used by priests and scribes), several of the papyri were dated to the end of the reign of the Pharaoh Khufu (ca. 2580–2550 B.C.). One of the documents was very specific, noting it was

In 2013, archaeologists discovered hundreds of papyrus fragments, some of them more than two feet long. The papyri had been deposited in front of galleries G1 and G2 where large blocking stones were placed to close off the entrance to the galleries. Written in hieratic (simplified hieroglyphics used by priests and scribes), several of the papyri were dated to the end of the reign of the Pharaoh Khufu (ca. 2580–2550 B.C.). One of the documents was very specific, noting it was  written the year after the 13th cattle count of Khufu’s reign. The cattle count was done every other year, so the year after the 13th cattle count was the 27th year, which according to our current best information was the last year of his reign. The precise dating identifies this papyrus as the oldest ever discovered in Egypt.

written the year after the 13th cattle count of Khufu’s reign. The cattle count was done every other year, so the year after the 13th cattle count was the 27th year, which according to our current best information was the last year of his reign. The precise dating identifies this papyrus as the oldest ever discovered in Egypt.

There are two types of documents in the papyrus group: accounts organized in tables anyone who has ever worked in Excel will immediately recognize, and the logbook of a Memphis official named Merer. The accounting tables record deliveries of food from areas elsewhere in Egypt including the Nile Delta. Revenue is recorded in red; outlay in black. Merer’s archive recorded the daily activities of his team of around 200 men,

There are two types of documents in the papyrus group: accounts organized in tables anyone who has ever worked in Excel will immediately recognize, and the logbook of a Memphis official named Merer. The accounting tables record deliveries of food from areas elsewhere in Egypt including the Nile Delta. Revenue is recorded in red; outlay in black. Merer’s archive recorded the daily activities of his team of around 200 men,  and as archaeological luck would have it, most of the surviving papyri don’t cover the minutiae of their operations at Wadi al-Jarf, but rather their work relating to the construction of the Great Pyramid at Giza. There are descriptions of quarrying the limestone, the transportation over the Nile and canals of massive blocks of stone from the quarries of Tura to the “Horizon of Khufu,” meaning the Giza construction site. These limestone blocks were probably used for the outer layer of the Great Pyramid, now lost, but which would have glowed white in the Egyptian sun.

and as archaeological luck would have it, most of the surviving papyri don’t cover the minutiae of their operations at Wadi al-Jarf, but rather their work relating to the construction of the Great Pyramid at Giza. There are descriptions of quarrying the limestone, the transportation over the Nile and canals of massive blocks of stone from the quarries of Tura to the “Horizon of Khufu,” meaning the Giza construction site. These limestone blocks were probably used for the outer layer of the Great Pyramid, now lost, but which would have glowed white in the Egyptian sun.

Merer’s logbook was found in the same archaeological context as the 13th cattle count document. It confirms that in Khufu’s last regnal year, the pyramid was in the final stage of construction. It also identifies the role of a major player, the pharaoh’s half-brother Ankh-haf who as “chief for all the works of the king” was in charge of this last phase of the Great Pyramid’s construction.

Merer’s logbook was found in the same archaeological context as the 13th cattle count document. It confirms that in Khufu’s last regnal year, the pyramid was in the final stage of construction. It also identifies the role of a major player, the pharaoh’s half-brother Ankh-haf who as “chief for all the works of the king” was in charge of this last phase of the Great Pyramid’s construction.

A selection of the papyri, including the 13th cattle count document, the largest pieces of Merer’s journal and the accounting spreadsheets have gone on display for the first time at Cairo’s Egyptian Museum. It will be a lightning quick exhibition, unfortunately, so unless you’re in Egypt right now or plan to be there in the next week or so, you’ll miss it. It opened on July 14th and closes on July 29th.

A selection of the papyri, including the 13th cattle count document, the largest pieces of Merer’s journal and the accounting spreadsheets have gone on display for the first time at Cairo’s Egyptian Museum. It will be a lightning quick exhibition, unfortunately, so unless you’re in Egypt right now or plan to be there in the next week or so, you’ll miss it. It opened on July 14th and closes on July 29th.