Archaeologists with Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) have discovered a system of canals that was built underneath the Temple of Inscriptions in Palenque where the Maya king K’inich Janaab’ Pakal (603-683 A.D.) was buried. The main canal is made of rows of large cut stones, clay and rubble. It has a limestone floor and is capped by a roof made of larger stones. It is a near square at 50 x 40 cm (1.6 x 1.3 feet) and is about 17 meters (55.8 feet) long. The main channel follows a straight line south under the temple, eventually widening into a basin 80 x 90 x 60 cm. To the southeast, there’s a second smaller channel (40 x 20 cm) that runs parallel to the main channel but about 20 cm higher level. The second channel eventually joins the main one which changes direction to the southwest and goes on at least another five meters (16.4 feet).

Archaeologists with Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) have discovered a system of canals that was built underneath the Temple of Inscriptions in Palenque where the Maya king K’inich Janaab’ Pakal (603-683 A.D.) was buried. The main canal is made of rows of large cut stones, clay and rubble. It has a limestone floor and is capped by a roof made of larger stones. It is a near square at 50 x 40 cm (1.6 x 1.3 feet) and is about 17 meters (55.8 feet) long. The main channel follows a straight line south under the temple, eventually widening into a basin 80 x 90 x 60 cm. To the southeast, there’s a second smaller channel (40 x 20 cm) that runs parallel to the main channel but about 20 cm higher level. The second channel eventually joins the main one which changes direction to the southwest and goes on at least another five meters (16.4 feet).

Because the canals are so small, archaeologists could only explore them by sending a remote-controlled vehicle equipped with a camera. The vehicle could not go around the sharp turn in the main canal, so as of now we don’t know where the canal ends. Archaeologists believe they are connected to an active water source as there is still running water in the canals today. Construction dates to the Maya late Classic Period (600-900 A.D.).

Excavations began in 2012 after a crack developed in the pyramid. A geophysical study found anomalies under the pyramid’s front steps. Concerned there might be a sinkhole or weak spot that could lead to serious structural damage to the pyramid, archaeologists dug test pits at the bottom of the temple’s main facade. They encountered a layer of large stones sealed together with clay. Underneath that was another layer of heavy stones packed with mud, and then a third and fourth layer of the same. It was under the fourth stone layer than the channel was found. The stone layers are all level and their width matches that of the north wall of Pakal’s burial chamber.

Excavations began in 2012 after a crack developed in the pyramid. A geophysical study found anomalies under the pyramid’s front steps. Concerned there might be a sinkhole or weak spot that could lead to serious structural damage to the pyramid, archaeologists dug test pits at the bottom of the temple’s main facade. They encountered a layer of large stones sealed together with clay. Underneath that was another layer of heavy stones packed with mud, and then a third and fourth layer of the same. It was under the fourth stone layer than the channel was found. The stone layers are all level and their width matches that of the north wall of Pakal’s burial chamber.

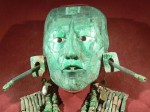

Pakal, who ruled the city-state of Palenque for 68 years, the longest known reign of any ruler in the Western hemisphere and the 30th longest reign in the world, began construction of his funerary monument in the last decade of his life. After he died, Pakal was deified and the temple completed by his son and successor K’inich Kan Bahlam II. When the tomb was discovered by archaeologist Alberto Ruz Lhuillier in 1952, Pakal’s remains were found in a sarcophagus with an elaborately carved lid. His face was covered by a jade death mask with large ear flares, also made of jade. The ear pieces have an inscription that claims that in order to be received by the god of the underworld, Pakal had to submerge himself in the waters of the rain god Chaac.

Pakal, who ruled the city-state of Palenque for 68 years, the longest known reign of any ruler in the Western hemisphere and the 30th longest reign in the world, began construction of his funerary monument in the last decade of his life. After he died, Pakal was deified and the temple completed by his son and successor K’inich Kan Bahlam II. When the tomb was discovered by archaeologist Alberto Ruz Lhuillier in 1952, Pakal’s remains were found in a sarcophagus with an elaborately carved lid. His face was covered by a jade death mask with large ear flares, also made of jade. The ear pieces have an inscription that claims that in order to be received by the god of the underworld, Pakal had to submerge himself in the waters of the rain god Chaac.

One of the newly discovered canals run directly underneath Pakal’s burial chamber, and the matching dimensions of the stone cap layers are probably not a coincidence. Archaeologists believe the canals were built first, tapping into the unknown source that is still supplying fresh water to the tunnels today, and the funerary pyramid constructed above them. One possibility is that they were originally built to drain rainwater from the terraces of Temple XXIV, just south of the Temple of the Inscriptions, but they wouldn’t need a river or spring source for that purpose. Although there has been no vertical conduit found connecting the burial chamber to the canal below, archaeologists believe there was a religious significance to the canals in keeping with the inscription on the ear flares on top of any practical purpose. The builders may have directed a river to flow under his tomb so that the king’s soul could travel unimpeded to the underworld via the waters of Chaac.

One of the newly discovered canals run directly underneath Pakal’s burial chamber, and the matching dimensions of the stone cap layers are probably not a coincidence. Archaeologists believe the canals were built first, tapping into the unknown source that is still supplying fresh water to the tunnels today, and the funerary pyramid constructed above them. One possibility is that they were originally built to drain rainwater from the terraces of Temple XXIV, just south of the Temple of the Inscriptions, but they wouldn’t need a river or spring source for that purpose. Although there has been no vertical conduit found connecting the burial chamber to the canal below, archaeologists believe there was a religious significance to the canals in keeping with the inscription on the ear flares on top of any practical purpose. The builders may have directed a river to flow under his tomb so that the king’s soul could travel unimpeded to the underworld via the waters of Chaac.

Investigations into the channel system will continue. Archaeologists would like to explore the main channel to its end, if not by remote camera that by using geophysical tools like ground penetrating radar to track the underground architectural features.