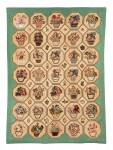

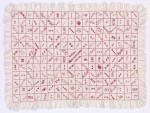

A new exhibit at the National Gallery of Victoria is putting on display an exceptional collection of quilts and related pieces from Australia’s rich history of patchwork. Making the Australian Quilt: 1800–1950 brings together almost 100 quilts, blankets, coverlets, and patchwork clothes from museums and private collections all over the country. They date to the first decades of English colonization through the middle of the 20th century. Some of the pieces have never been on public display, like the Hexagon quilt made in 1811 by Sarah Wall (nee Litherland or Leatherland), an English convict who arrived in Australia about the HMS Earl Cornwallis in 1801, 13 years after the first convicts arrived in Botany Bay and eight years after the first free settlers. Hers is the earliest known pierced hexagon quilt made in Australia.

A new exhibit at the National Gallery of Victoria is putting on display an exceptional collection of quilts and related pieces from Australia’s rich history of patchwork. Making the Australian Quilt: 1800–1950 brings together almost 100 quilts, blankets, coverlets, and patchwork clothes from museums and private collections all over the country. They date to the first decades of English colonization through the middle of the 20th century. Some of the pieces have never been on public display, like the Hexagon quilt made in 1811 by Sarah Wall (nee Litherland or Leatherland), an English convict who arrived in Australia about the HMS Earl Cornwallis in 1801, 13 years after the first convicts arrived in Botany Bay and eight years after the first free settlers. Hers is the earliest known pierced hexagon quilt made in Australia.

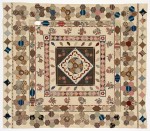

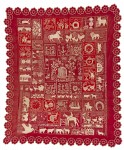

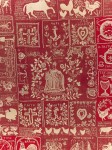

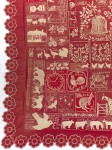

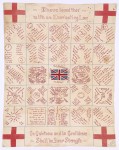

Others are so fragile they’ve only been shown very rarely. The most signficant of these is The Rajah Quilt, made in 1841 by the female convicts transported to Australia aboard the HMS Rajah. It is the only known surviving quilt made during the voyage from London to Van Diemen’s Land. The necessary supplies were donated by The British Ladies Society for Promoting the Reformation of Female Prisoners. Founded in 1821 by the Quaker prison reform advocate Elizabeth Fry, the society distributed bibles, combs, sewing supplies for personal use and all the materials needed for a collaborative quilt — 100 needles, pins, white, black, red and blue cotton thread, black wool, 24 hanks of coloured thread, and two pounds of patchwork pieces — to female convicts, first at Newgate prison, and then to transportees.

Others are so fragile they’ve only been shown very rarely. The most signficant of these is The Rajah Quilt, made in 1841 by the female convicts transported to Australia aboard the HMS Rajah. It is the only known surviving quilt made during the voyage from London to Van Diemen’s Land. The necessary supplies were donated by The British Ladies Society for Promoting the Reformation of Female Prisoners. Founded in 1821 by the Quaker prison reform advocate Elizabeth Fry, the society distributed bibles, combs, sewing supplies for personal use and all the materials needed for a collaborative quilt — 100 needles, pins, white, black, red and blue cotton thread, black wool, 24 hanks of coloured thread, and two pounds of patchwork pieces — to female convicts, first at Newgate prison, and then to transportees.

Elizabeth Fry had a great impact on the way women sentenced to transportation were treated. She ensured they were taken to the ships in closed carriages so they wouldn’t be subject to the stone-throwing, filth projectiles and derision of the public. Loaded onto ships weeks before they sailed, the prisoners were horribly neglected. Fry and the ladies of the Society visited them every day, tending to their needs and giving them care packages that included the needlecraft supplies.

Elizabeth Fry had a great impact on the way women sentenced to transportation were treated. She ensured they were taken to the ships in closed carriages so they wouldn’t be subject to the stone-throwing, filth projectiles and derision of the public. Loaded onto ships weeks before they sailed, the prisoners were horribly neglected. Fry and the ladies of the Society visited them every day, tending to their needs and giving them care packages that included the needlecraft supplies.

Fry thought patchwork in particular was ideal employment for women prisoners, because it taught them how to sew and, because it’s so complex and time-consuming, it gave them something to focus on during the long dreary hours of confinement. At the end, they’d have new skills and a beautiful result to show for their hard work. Patchwork converted the drudgery of a prison sentence, or a dangerous, unpleasant three-month ship voyage across the world, into productive time. It also had a meditative quality, an inward-looking contemplation which in Fry’s Quaker philosophy led to spiritual salvation.

The 180 female convicts on the Rajah were given patchwork materials by the Society and guidance in the person of Miss Keiza Hayter. Hayter was not a convict. She had worked with Fry at the Millbank Penitentiary, and Fry recommended her to Lady Jane Franklin to help found the Tasmanian Ladies’ Society for the Reformation of Female Prisoners. Yes, that Lady Jane Franklin. John Franklin was lieutenant-governor of Van Diemen’s Land when the Rajah unloaded its women convicts and their quilt, and Lady Franklin was in regular contact with Elizabeth Fry. It was Fry who inspired her prison reform efforts in Tasmania, a colony largely populated with current and former convicts, although Jane did not share Fry’s focus on rehabilitation. Lady Franklin believed hard labour, long stretches of solitary confinement and shaving female prisoners’ heads were more effective means to instill “corrective discipline” than contemplation and job training.

The 180 female convicts on the Rajah were given patchwork materials by the Society and guidance in the person of Miss Keiza Hayter. Hayter was not a convict. She had worked with Fry at the Millbank Penitentiary, and Fry recommended her to Lady Jane Franklin to help found the Tasmanian Ladies’ Society for the Reformation of Female Prisoners. Yes, that Lady Jane Franklin. John Franklin was lieutenant-governor of Van Diemen’s Land when the Rajah unloaded its women convicts and their quilt, and Lady Franklin was in regular contact with Elizabeth Fry. It was Fry who inspired her prison reform efforts in Tasmania, a colony largely populated with current and former convicts, although Jane did not share Fry’s focus on rehabilitation. Lady Franklin believed hard labour, long stretches of solitary confinement and shaving female prisoners’ heads were more effective means to instill “corrective discipline” than contemplation and job training.

Keiza Hayter’s mission on the Rajah was to instill useful values and skills in the transportees. Part of that was the improvement of their minds and characters through needlework. Experts believe Hayter oversaw the design of the quilt. It has a central square of Broderie Perse (appliquéd chintz that resembles Persian embroidery) from which twelve frames radiate forming a medallion quilt. Florals and birds decorate the center and frames. Experts believe at least 29 of the transportees worked on the quilt. The passenger manifest lists 15 women whose professions were tailoring/needlework, but there’s evidence on the quilt itself that novices worked on it as well. Small bloodstains were probably left by less experienced women when they stuck themselves with needles.

Keiza Hayter’s mission on the Rajah was to instill useful values and skills in the transportees. Part of that was the improvement of their minds and characters through needlework. Experts believe Hayter oversaw the design of the quilt. It has a central square of Broderie Perse (appliquéd chintz that resembles Persian embroidery) from which twelve frames radiate forming a medallion quilt. Florals and birds decorate the center and frames. Experts believe at least 29 of the transportees worked on the quilt. The passenger manifest lists 15 women whose professions were tailoring/needlework, but there’s evidence on the quilt itself that novices worked on it as well. Small bloodstains were probably left by less experienced women when they stuck themselves with needles.

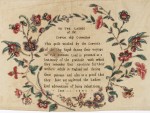

A silk yarn inscription expresses the convicts’ proper sentiments of gratitude and industriousness.

of the

Convict ship committee.

This quilt worked by the Convicts

of the ship Rajah during their voyage

to van Diemans Land is presented as a

testimony to the gratitude with which

they remember their exertions for their

welfare while in England and during

their passage and also as proof that

they have not neglected the Ladies

kind admonition of being industrious.

June 1841

The quilt is now in the permanent collection of the National Gallery of Australia. It has survived in remarkable condition, all told, but it is very fragile and light-sensitive so for conservation’s sake, it is only displayed once a year.

The quilt is now in the permanent collection of the National Gallery of Australia. It has survived in remarkable condition, all told, but it is very fragile and light-sensitive so for conservation’s sake, it is only displayed once a year.

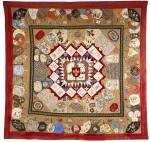

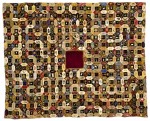

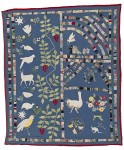

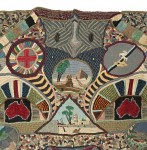

That’s just scratching the surface of the beautiful works on view at this exhibition which opens today and runs through November 16th. Because the museum was kind enough to supply outstanding photographs of many stand-out pieces and because I know there are many needlework afficionados reading this, here’s a generous complement of quilt porn to take you into the weekend. And not just quilts either. The Press Dress, an unbelievable ball gown worn by Mrs. William W. Dobbs to the the Mayor of Melbourne’s fancy dress ball in 1866, was made of silk satin printed with pages of 14 different Melbourne newspapers, including The Age, The Australasian, Herald and Punch. I love the table cover made from cigar silk, too. Oh! And the Westbury Sampler quilt! It’s all deadly.