At the Battle of Teutoburg Forest in 9 A.D., three legions, six cohorts of auxiliary troops and three squadrons of cavalry led by Publius Quintilius Varus were slaughtered by Germanic tribesmen led Arminius. Arminius was the son of Cherusci king who had been sent to Rome as a hostage when he was a child. There he received a military education and achieved the rank of Equites. He was deployed to Germania as Varus’ advisor where he secretly united tribes that had been at each other’s throats for years. While feeding Varus misinformation, Arminius used his knowledge of Roman military tactics to manipulate commander and legions into a disastrously indefensible position inside the forest. By the end of the battle, 15,000 to 20,000 Roman troops were dead. Varus and several of his officers committed suicide. Only about 1,000 men survived.

At the Battle of Teutoburg Forest in 9 A.D., three legions, six cohorts of auxiliary troops and three squadrons of cavalry led by Publius Quintilius Varus were slaughtered by Germanic tribesmen led Arminius. Arminius was the son of Cherusci king who had been sent to Rome as a hostage when he was a child. There he received a military education and achieved the rank of Equites. He was deployed to Germania as Varus’ advisor where he secretly united tribes that had been at each other’s throats for years. While feeding Varus misinformation, Arminius used his knowledge of Roman military tactics to manipulate commander and legions into a disastrously indefensible position inside the forest. By the end of the battle, 15,000 to 20,000 Roman troops were dead. Varus and several of his officers committed suicide. Only about 1,000 men survived.

The defeat was so decisive it had long-term consequences to Rome’s plans for Germania. Roman legions would fight German tribes east of the Rhine, even east of the Teutoburg Forest again, but Rome never gained the permanent foothold in Germany between the Rhine and the Elbe it had in Gaul or Britain.

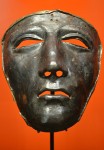

The precise location of the battlefield was lost for thousands of years until the late 1980s when a metal detectorist found coins from the reign of Augustus and lead sling-bullets at Kalkriese Hill in Osnabrück county, Lower Saxony. Starting in 1989, the site was formally excavated and archaeologists unearthed human and animal bones, and Roman military artifacts like fragments of hobnailed sandals, spearheads, iron keys and one officer’s ceremonial face mask. They also found earthworks defenses 15 miles wide and evidence that the Romans had attempted to breach them but failed, just as Cassius Dio had described (Roman History, Book 56, Chapter 18).

The precise location of the battlefield was lost for thousands of years until the late 1980s when a metal detectorist found coins from the reign of Augustus and lead sling-bullets at Kalkriese Hill in Osnabrück county, Lower Saxony. Starting in 1989, the site was formally excavated and archaeologists unearthed human and animal bones, and Roman military artifacts like fragments of hobnailed sandals, spearheads, iron keys and one officer’s ceremonial face mask. They also found earthworks defenses 15 miles wide and evidence that the Romans had attempted to breach them but failed, just as Cassius Dio had described (Roman History, Book 56, Chapter 18).

A museum and archaeological park were built at Kalkriese Hill in the early 2000, with the 20 hectares of the site open to the public as excavations continue. During this season’s excavation, a team from the Kalkriese Museum and Park and Osnabrück University found six gold coins, Augustan aurei, on June 9th. The next day they found three more. In the past 25 years, excavations at the site have unearthed two gold coins and 800 silver and bronze ones, so finding eight within a few meters of each other on two consecutive days is a great rarity.

Minted in Lugdunum (modern-day Lyons) from 2 B.C. until 4 A.D., the aurei are of the Gaius-Lucius type, coins dedicated to Augustus’ grandsons. On the reverse the young Caesars are depicted wearing togas, one hand on a shield with a spear behind it. A simplum and lituus, emblems of priestly rank, hover between them. The inscription reads AVGVSTI F COS DESIG PRINC IVVENT (“sons of Augustus, consuls-designate and leaders of the youth”). The obverse is a profile head of Augustus wearing a laurel wreath inscribed CAESAR AVGVSTVS DIVI F PATER PATRIAE (“Caesar Augustus, son of the deified [Julius Caesar], Father of the Nation”).

Minted in Lugdunum (modern-day Lyons) from 2 B.C. until 4 A.D., the aurei are of the Gaius-Lucius type, coins dedicated to Augustus’ grandsons. On the reverse the young Caesars are depicted wearing togas, one hand on a shield with a spear behind it. A simplum and lituus, emblems of priestly rank, hover between them. The inscription reads AVGVSTI F COS DESIG PRINC IVVENT (“sons of Augustus, consuls-designate and leaders of the youth”). The obverse is a profile head of Augustus wearing a laurel wreath inscribed CAESAR AVGVSTVS DIVI F PATER PATRIAE (“Caesar Augustus, son of the deified [Julius Caesar], Father of the Nation”).

The sons of Augustus’ daughter Julia and Marcus Agrippa, Gaius and Lucius were adopted by their grandfather in 17 B.C. when Gaius was three and Lucius was an infant. He made them his heirs and turbocharged them into political careers when they were still teenagers. Augustus’ hopes were dashed when Lucius died of a sudden illness in 2 A.D. and Gaius died two years later after being wounded in battle. Tacitus suggests their stepmother Livia may have had a hand in their deaths in order to elevate her own son Tiberius to the imperial throne.

After Gaius’ death in 4 A.D., the coins were no longer produced. The eight coins found on the battle site are well-preserved, but they show signs of having been in circulation, particularly in the wear around the edges. Aurei were very valuable, used mainly for large purchases and ceremonial gifts. Standard legionary pay under Augustus was 300 bronze asses a month, the equivalent of about 19 denarii. An aureus was worth 25 denarii. Legionaries didn’t usually get their full pay while they were in the field because carrying around increasing hundreds of bronze coins for years quickly goes from bulky to impossible. It was saved for when the campaign was over or sent to their families.

After Gaius’ death in 4 A.D., the coins were no longer produced. The eight coins found on the battle site are well-preserved, but they show signs of having been in circulation, particularly in the wear around the edges. Aurei were very valuable, used mainly for large purchases and ceremonial gifts. Standard legionary pay under Augustus was 300 bronze asses a month, the equivalent of about 19 denarii. An aureus was worth 25 denarii. Legionaries didn’t usually get their full pay while they were in the field because carrying around increasing hundreds of bronze coins for years quickly goes from bulky to impossible. It was saved for when the campaign was over or sent to their families.

Only an officer was likely to have the wherewithal to have a bunch of aurei on his person. Since these coins were found so close together and relatively near the surface, archaeologists believe they may have been in a bag of cash an officer was carrying during the battle. It was dropped in the conflict or perhaps hidden before a flight attempt and the bag decayed, leaving only its shiny contents to be discovered 2,000 years later.