A new study of the Grolier Codex, a pre-Hispanic book of Maya hieroglyphics whose authenticity has been in doubt since it first came to light under extremely shady circumstances in 1971, has determined that it is genuine and may even be the oldest of only four ancient American codices known to survive.

A new study of the Grolier Codex, a pre-Hispanic book of Maya hieroglyphics whose authenticity has been in doubt since it first came to light under extremely shady circumstances in 1971, has determined that it is genuine and may even be the oldest of only four ancient American codices known to survive.

The earliest conclusively dated Maya text, painted on pyramid walls in San Bartolo, Guatemala, dates to 300 B.C., and since the writing system was well-developed by then, it goes back even further. There is evidence of Olmec writing and paper production from the first millennium B.C. Murals  and carved reliefs are most of what remains today, even though for centuries Maya scribes recorded astronomical observations, histories, religious texts, mathematical calculations, calendars and much more on pages made of the inner bark of fig trees. The Spanish conquistadors were suspicious of what they didn’t understand, so naturally they destroyed it, sending the Maya’s long, rich literary tradition up in smoke.

and carved reliefs are most of what remains today, even though for centuries Maya scribes recorded astronomical observations, histories, religious texts, mathematical calculations, calendars and much more on pages made of the inner bark of fig trees. The Spanish conquistadors were suspicious of what they didn’t understand, so naturally they destroyed it, sending the Maya’s long, rich literary tradition up in smoke.

Diego de Landa Calderón, future bishop of Yucatán, saw heresy and idolatry everywhere among the freshly converted and in their mysterious hieroglyphic texts. When he and his inquisitors weren’t torturing literally thousands of Maya nobles and commoners alike, they were burning their books.

We found a large number of books in these characters and, as they contained nothing in which were not to be seen as superstition and lies of the devil, we burned them all, which they (the Maya) regretted to an amazing degree, and which caused them much affliction.

He wasn’t alone in his zeal. On top of that, the Spanish occupiers outlawed the production of paper, ensuring that what was lost could not be easily recreated. A handful of Maya codices were sent to Europe as curiosities. Today three of them are extant: one in Dresden, one in Madrid and one in Paris.

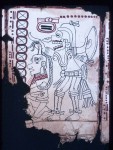

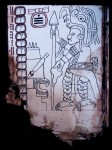

In 1971, a previously unknown Maya codex was displayed at the Grolier Club in New York City. Eleven pages of fig bark paper, each stuccoed on both sides but painted only on one, had numerical and calendrical glyphs on the left side of every page and a single large illustration of a figure on the center right. The text describes the movements of Venus.

In 1971, a previously unknown Maya codex was displayed at the Grolier Club in New York City. Eleven pages of fig bark paper, each stuccoed on both sides but painted only on one, had numerical and calendrical glyphs on the left side of every page and a single large illustration of a figure on the center right. The text describes the movements of Venus.

The codex was part of an exhibition curated by archaeologist Michael Coe who had a crazy story to tell about how he managed to get his hands on such an incredible rarity. A friend told him that Mexican collector Josué Sáenz had acquired what seemed to be a genuine Mayan codex in 1966. Coe went to Mexico City, met with Sáenz and examined the codex, ultimately finding it plausibly authentic. He asked the collector how he had found it and Sáenz told him quite the origin story.

Someone had contacted Sáenz, goes the tell, offering to sell him an ancient codex if he would fly to an unnamed destination to see it and tell nobody. So, accompanied by two men, he clambered into a tiny plane whose compass was covered with a cloth. This rudimentary device to hide the location failed because Sáenz recognized the destination as the foothills of the Sierra de Chiapas. (Blindfolds, people. Have TV and movie kidnappings taught us nothing?) There he was shown the codex, a wooden mask and a sacrificial knife the sellers claimed to have found in a dry cave somewhere undetermined. Even though his expert considered the codex and artifacts fakes, Sáenz went with his gut and bought them.

Someone had contacted Sáenz, goes the tell, offering to sell him an ancient codex if he would fly to an unnamed destination to see it and tell nobody. So, accompanied by two men, he clambered into a tiny plane whose compass was covered with a cloth. This rudimentary device to hide the location failed because Sáenz recognized the destination as the foothills of the Sierra de Chiapas. (Blindfolds, people. Have TV and movie kidnappings taught us nothing?) There he was shown the codex, a wooden mask and a sacrificial knife the sellers claimed to have found in a dry cave somewhere undetermined. Even though his expert considered the codex and artifacts fakes, Sáenz went with his gut and bought them.

Eventually the Mexican government made a legal claim on the codex and Sáenz donated it to the nation. It has been kept at the National Museum in Mexico City ever since, out of public view for its own protection.

The only pre-Hispanic codex found in the 20th century, the discovery of one that survived the conflagration without having been shipped across the Atlantic was explosive, but immediately its authenticity was questioned, and indeed how could it not be when it sprang up out of nowhere courtesy of looters, and that’s assuming the cloak-and-dagger background story was accurate. There were anomalies in the document as well. The figures are drawn in Mixtec style with Toltec attire, and the numbering system is inconsistent. Also, none of the three confirmed authentic codices are painted only one side of the pages.

The only pre-Hispanic codex found in the 20th century, the discovery of one that survived the conflagration without having been shipped across the Atlantic was explosive, but immediately its authenticity was questioned, and indeed how could it not be when it sprang up out of nowhere courtesy of looters, and that’s assuming the cloak-and-dagger background story was accurate. There were anomalies in the document as well. The figures are drawn in Mixtec style with Toltec attire, and the numbering system is inconsistent. Also, none of the three confirmed authentic codices are painted only one side of the pages.

Radiocarbon dating of the bark paper found it was made around 1230, so it was definitely genuine, but it was always possible that looters had found blank pages and had someone draw something Mayanesque on them to make them saleable. Michael Coe published the results of his investigations into the codex in 1973 (pdf).

The debate has raged ever since. Now researchers, led by Brown University’s Stephen Houston, have reexamined everything about the codex in an attempt to answer all the questions raised about it.

The Grolier’s composition, from its 13th-century amatl paper, to the thin red sketch lines underlying the paintings and the Maya blue pigments used in them, are fully persuasive, the authors assert. Houston and his coauthors outline what a 20th century forger would have had to know or guess to create the Grolier, and the list is prohibitive: he or she would have to intuit the existence of and then perfectly render deities that had not been discovered in 1964, when any modern forgery would have to have been completed; correctly guess how to create Maya blue, which was not synthesized in a laboratory until Mexican conservation scientists did so in the 1980s; and have a wealth and range of resources at their fingertips that would, in some cases, require knowledge unavailable until recently. […]

The Grolier’s composition, from its 13th-century amatl paper, to the thin red sketch lines underlying the paintings and the Maya blue pigments used in them, are fully persuasive, the authors assert. Houston and his coauthors outline what a 20th century forger would have had to know or guess to create the Grolier, and the list is prohibitive: he or she would have to intuit the existence of and then perfectly render deities that had not been discovered in 1964, when any modern forgery would have to have been completed; correctly guess how to create Maya blue, which was not synthesized in a laboratory until Mexican conservation scientists did so in the 1980s; and have a wealth and range of resources at their fingertips that would, in some cases, require knowledge unavailable until recently. […]

The codex is also, according to the paper’s authors, not a markedly beautiful book. “In my view, it isn’t a high-end production,” Houston said, “not one that would be used in the most literate royal court. The book is more closely focused on images and the meanings they convey.”

The Grolier Codex, the team argues, is also a “predetermined rather than observational” guide, meaning it declares what “should occur rather than what could be seen through the variable cloud cover of eastern Mesoamerica. With its span of 104 years, the Grolier would have been usable for at least three generations of calendar priest or day-keeper,” the authors write.

That places the Grolier in a different tradition than the Dresden Codex, which is known for its elaborate notations and calculations, and makes the Grolier suitable for a particular kind of readership, one of moderately high literacy. It may also have served an ethnically and linguistically mixed group, in part Maya, in part linked to the Toltec civilization centered on the ancient city of Tula in Central Mexico.

The study has been published in the journal Maya Archaeology. It includes a facsimile of the entire codex.

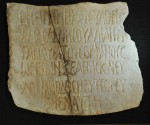

An Egyptian epitaph from the 3rd century A.D. has been recently translated revealing a unique combination of descriptors. The epitaph is part of a collection of Greek and Coptic artifacts in the University of Utah’s J. Willard Marriott Library. The collection was donated to the library in 1989 after the death of the collector, Doctor Aziz Suryal Atiya, an eminent Coptic historian who taught history at the University of Utah and founded the university’s Middle East Center in 1959. The Aziz S. Atiya Middle East Library, an internationally renown center for research in Middle Eastern history with the fifth largest collection in the United States, has hundreds of thousands of books, manuscripts and rare artifacts.

An Egyptian epitaph from the 3rd century A.D. has been recently translated revealing a unique combination of descriptors. The epitaph is part of a collection of Greek and Coptic artifacts in the University of Utah’s J. Willard Marriott Library. The collection was donated to the library in 1989 after the death of the collector, Doctor Aziz Suryal Atiya, an eminent Coptic historian who taught history at the University of Utah and founded the university’s Middle East Center in 1959. The Aziz S. Atiya Middle East Library, an internationally renown center for research in Middle Eastern history with the fifth largest collection in the United States, has hundreds of thousands of books, manuscripts and rare artifacts.“I’ve looked at hundreds of ancient Jewish epitaphs,” Blumell said, “and there is nothing quite like this. This is a beautiful remembrance and tribute to this woman.” […]

I had doubts about that life expectancy statistic. I thought it might be a misinterpretation of average life expectancy, an average which is extremely low in places and times when infant and child mortality was high. The average age of death skews far younger because so many children died young. Once people managed to survive to adulthood their real life expectancy was significantly higher. I was wrong. According to ancient census data from Egypt in the first three centuries A.D., fully 61% of women were dead by the age of 30. Men had it only slightly better with 59% dying before they hit their 30s. Helene was one of fewer than 6% of Egyptian women from this period who lived to see 60.

I had doubts about that life expectancy statistic. I thought it might be a misinterpretation of average life expectancy, an average which is extremely low in places and times when infant and child mortality was high. The average age of death skews far younger because so many children died young. Once people managed to survive to adulthood their real life expectancy was significantly higher. I was wrong. According to ancient census data from Egypt in the first three centuries A.D., fully 61% of women were dead by the age of 30. Men had it only slightly better with 59% dying before they hit their 30s. Helene was one of fewer than 6% of Egyptian women from this period who lived to see 60.