The SS Tuscania, built as an ocean cruiser of Cunard’s Anchor Line, was one of the first troop ships to carry US soldiers to the Western Front in World War I. While war had been declared against Germany in April of 1917, the sleeping giant took months to rouse, with war declared against Austria-Hungary in December 1917 and actual troop movements only beginning in early 1918. Full-scale mobilization would not take place for weeks after that.

The SS Tuscania, built as an ocean cruiser of Cunard’s Anchor Line, was one of the first troop ships to carry US soldiers to the Western Front in World War I. While war had been declared against Germany in April of 1917, the sleeping giant took months to rouse, with war declared against Austria-Hungary in December 1917 and actual troop movements only beginning in early 1918. Full-scale mobilization would not take place for weeks after that.

The Tuscania departed from Hoboken, New Jersey, on January 24th, 1918, with 2,164 US Army troops and 239 crew members headed for Liverpool on the way to its ultimate destination, the port of Le Havre in France. It made it as far as the Hebridean waters seven miles off the coast of the Scottish island of Islay where on the night of February 5th German U-Boat 77 torpedoed it. The ship suffered a direct hit and sank in a matter of hours.

The ship was abandoned in orderly, efficient fashion, but many of the damaged lifeboats capsized in the cold, rough sea. The British destroyers Mosquito, Grasshopper and Pigeon saved 1,500 or so men. An estimated 230 men either went down with the ship or were lost in the aftermath.

The ship was abandoned in orderly, efficient fashion, but many of the damaged lifeboats capsized in the cold, rough sea. The British destroyers Mosquito, Grasshopper and Pigeon saved 1,500 or so men. An estimated 230 men either went down with the ship or were lost in the aftermath.

Many of the survivors, in lifeboats or not, washed ashore on Islay’s treacherous shoals. The people of Islay responded to the disaster with selfless dedication. More than 100 sons of Islay had died in World War I by this point, and their families felt keenly the loss of life of the American lads who had just joined the fight.

Robert Morrison, a shepherd and farmer, was one of several Islay men who risked death to rescue soldiers and crew from the shoals. After personally saving three men, he and his family took 90 survivors into their small cottage and nursed them back to health, losing only two men, one from exhaustion shortly after the sinking, the other three days later from pneumonia. They used up every last morsel of their food stores and all the clothing in caring for the Tuscania troops but categorically refused repayment from the Red Cross. An American Red Cross officer who liaised with Morrison described him in the official report as “one of the greatest heroes that I ever heard of.”

Robert Morrison, a shepherd and farmer, was one of several Islay men who risked death to rescue soldiers and crew from the shoals. After personally saving three men, he and his family took 90 survivors into their small cottage and nursed them back to health, losing only two men, one from exhaustion shortly after the sinking, the other three days later from pneumonia. They used up every last morsel of their food stores and all the clothing in caring for the Tuscania troops but categorically refused repayment from the Red Cross. An American Red Cross officer who liaised with Morrison described him in the official report as “one of the greatest heroes that I ever heard of.”

In total, 132 men were rescued on Islay. The villagers’ heroic efforts didn’t end there. They again risked life and limb to wade into the sharp breakers to retrieve the bodies of 183 men who had died in the disaster. The whole island worked tirelessly to treat the perished with the utmost respect and care. The public hall was used as a mortuary where the battered bodies were cleaned and every distinguishing characteristic recorded in police sergeant Malcolm MacNeill’s notebooks to make it possible for the families of the deceased to identify them. Hugh Morrison, Laird of Islay, donated land and timber. In less than three days, four cemeteries were created, and coffins and shrouds made for all of the dead.

In total, 132 men were rescued on Islay. The villagers’ heroic efforts didn’t end there. They again risked life and limb to wade into the sharp breakers to retrieve the bodies of 183 men who had died in the disaster. The whole island worked tirelessly to treat the perished with the utmost respect and care. The public hall was used as a mortuary where the battered bodies were cleaned and every distinguishing characteristic recorded in police sergeant Malcolm MacNeill’s notebooks to make it possible for the families of the deceased to identify them. Hugh Morrison, Laird of Islay, donated land and timber. In less than three days, four cemeteries were created, and coffins and shrouds made for all of the dead.

But even this Herculean effort was not sufficient for the good people of Islay. They wanted to bury the fallen with the honor and dignity they deserved, and that required an American flag. There was none to be had on Islay or anywhere else within easy range and as time was a factor, the villagers decided to make one. With nothing but an encyclopedia as a reference, Jessie McLellan, Mary Cunningham, Catherine McGregor, Mary Armour and John McDougall stayed up all night on February 7th to cut and stitch together seven red bars, six white ones and 48 white stars. In just a few hours they produced a proper US flag 67 inches long and 37 inches wide.

But even this Herculean effort was not sufficient for the good people of Islay. They wanted to bury the fallen with the honor and dignity they deserved, and that required an American flag. There was none to be had on Islay or anywhere else within easy range and as time was a factor, the villagers decided to make one. With nothing but an encyclopedia as a reference, Jessie McLellan, Mary Cunningham, Catherine McGregor, Mary Armour and John McDougall stayed up all night on February 7th to cut and stitch together seven red bars, six white ones and 48 white stars. In just a few hours they produced a proper US flag 67 inches long and 37 inches wide.

On February 8th, under the newly-made Stars and Stripes, a pre-existing Union Jack and accompanied by the mournful sound of traditional Scottish bagpipes, the firs group dead soldiers were buried, their surviving comrades serving as pallbearers. Over the next few days, the rest were buried in the four cemeteries. All of the bodies except for one would eventually be exhumed and returned to the United States for reburial.

The flag was gifted by the people of Islay to Woodrow Wilson, with the request that he give it a museum. He gave it to the Smithsonian Institution where it was put on display until at least 1927. Eventually it ended up in storage at the National Museum of Natural History.

The flag was gifted by the people of Islay to Woodrow Wilson, with the request that he give it a museum. He gave it to the Smithsonian Institution where it was put on display until at least 1927. Eventually it ended up in storage at the National Museum of Natural History.

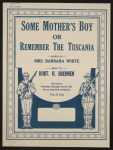

Despite the posters and songs exhorting the American public to “Remember the Tuscania,” it has been eclipsed in the collective consciousness and in history texts by the Lusitania, even though the latter wasn’t a troopship and was torpedoed fully two years before the US entered the war. Islay, however, has never forgotten. This year was the centennial of the disaster and Islay held two services on February 5th in honor of the lost.

Despite the posters and songs exhorting the American public to “Remember the Tuscania,” it has been eclipsed in the collective consciousness and in history texts by the Lusitania, even though the latter wasn’t a troopship and was torpedoed fully two years before the US entered the war. Islay, however, has never forgotten. This year was the centennial of the disaster and Islay held two services on February 5th in honor of the lost.

On May 4th, Islay will commemorate the sacrifices made in World War I with an International Service of Remembrance for the Tuscania disaster, the HMS Otranto collision (which took place in October of 1918) and the men of Islay who fought and died in the war. On its way to join the solemnities is the Islay American flag. The Smithsonian has loaned it to the Museum of Islay Life where it will be on display for five months, a symbol of the dedication, sacrifice and respect shown by the people of Islay to the American doughboys, survivor and fallen alike.