While leafing through an old Nancy Drew book of mine last week, I found a little pamphlet called “The Art of Kissing” by Clement Wood. It was published in 1926 by the Haldeman-Julius Company as part of their Little Blue Blook series. It seems appropriate that I pay this compendium of kissing history and practice my blogging respects on Valentine’s Day.

While leafing through an old Nancy Drew book of mine last week, I found a little pamphlet called “The Art of Kissing” by Clement Wood. It was published in 1926 by the Haldeman-Julius Company as part of their Little Blue Blook series. It seems appropriate that I pay this compendium of kissing history and practice my blogging respects on Valentine’s Day.

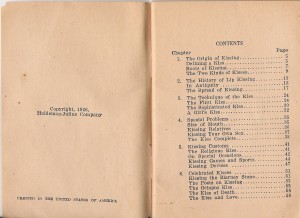

Sadly, its original blue cover is long gone, but the content has remained unscathed. The 3½ x 5 inch volume is 55 pages long and includes such awesome chapter headings as The Two Kinds of Kisses (lip and nose, or osculus Europeanus and osculus Asiaticus), Size of Mouth and Kissing Devices. From the Size of Mouth section:

Sadly, its original blue cover is long gone, but the content has remained unscathed. The 3½ x 5 inch volume is 55 pages long and includes such awesome chapter headings as The Two Kinds of Kisses (lip and nose, or osculus Europeanus and osculus Asiaticus), Size of Mouth and Kissing Devices. From the Size of Mouth section:

The excessively small mouth is easily kissed, and at times is far less satisfying than a good mouth-filling pair of lips. The medium-sized mouth, in normal cases, gives the greatest pleasure. When the man is confronted with a mouth whose general stretch, if laid on the ground, would apparently reach from Ft. Desbrosses, Alaska, to the corner of Main Street and Zenith Avenue, Skaneateles, New York, the matter is purely one of measuration in applied physics. The safest way is to start at one corner and gradually progress toward the center, covering ground as effectively as possibly in the process. The foolhardy at times make a dive for the very center at the beginning, and may encounter the emotion of having stepped off of a neck-high stretch in the river into a pool of immeasurable depth. If this is definitely the case, the only thing to do is to paddle toward one side or the other, in the hope of reaching firm ground once more.

You can see why it sold 257,500 copies in its day. Clement Wood’s entertaining style and penchant for risque subjects like “Byron and the Women He Loved” and “Modern Sexual Morality” made many of his 57 Little Blue Books among the highest sellers of the series.

He was famously prolific, cranking out not just these pamphlets but also books of poetry under his own name and ghostwritten novels at a breakneck pace of 80,000 words a month. He also wrote history books, reference works, literary criticism, joke books (including ones dedicated to ethnic stereotype humor that probably make for cringingly bad reading today), biographies and much more. One of the Little Blue Book manuscripts he wrote, The Complete Rhyming Dictionary, remains a big seller still in print today and in fact saved my no-talent ass in more than one poetry class.

He was famously prolific, cranking out not just these pamphlets but also books of poetry under his own name and ghostwritten novels at a breakneck pace of 80,000 words a month. He also wrote history books, reference works, literary criticism, joke books (including ones dedicated to ethnic stereotype humor that probably make for cringingly bad reading today), biographies and much more. One of the Little Blue Book manuscripts he wrote, The Complete Rhyming Dictionary, remains a big seller still in print today and in fact saved my no-talent ass in more than one poetry class.

Wood lived as varied a life as his bibliography would suggest. He was born in Tuscaloosa, Alabama in 1888. At first he followed in his father’s footsteps and went to law school. He seems to have been good at it, as he made assistant editor of the Yale Law Journal and would be made a judge in Birmingham’s Central Recorder’s Court in 1913, just 2 years after getting his law degree. His Socialist leanings didn’t exactly endear him to the Alabama political establishment, however, and he was removed from the bench almost as soon as he got there.

After that, he moved to Greenwich Village, New York, where he got work waiting tables, as a vice commission staffer, and, briefly, as secretary to Pulitzer Prize-winning author Upton Sinclair. He was writing a humor column for the Socialist daily The New York Call in 1915 when he met Emanuel Julius. When some years later Emanuel, now married to Marcet Haldeman and in a remarkably progressive move legally renamed to a combination of both their names, Haldeman-Julius, started a publishing company dedicated to producing cheap, educational and entertaining books for the working man’s pocket, he commissioned Wood to do some of the writing.

The endeavor was enormously successful, and Haldeman-Julius became famous. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch dubbed him “the Henry Ford of Literature” (only without the strike-breaking).

The endeavor was enormously successful, and Haldeman-Julius became famous. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch dubbed him “the Henry Ford of Literature” (only without the strike-breaking).

Though occasionally skeptical of his methods, the mainstream media eventually took note of Haldeman-Julius’s successes. The New Republic wrote that “the volume of his sales [is] so fantastic as to make his business almost a barometer of plebian taste”; a New Yorker profile observed that Haldeman-Julius must feel “the crusader’s pride” when, riding the subway on a visit to New York, “he sees a workman settle back on his strap and reach automatically to the pocket where he keeps his Little Blue Book.” Perhaps the most effusive praise came in a 1924 McClure’s article, which claimed that Little Blue Books were “spreading like beneficent locusts over the country,” and suggested that they would “help break down America’s cultural isolation.” “The best peace propaganda in the world is to make the culture of the whole world known to the whole world,” the article enthused, calling Haldeman-Julius “a creative genius who was blazing a more glorious path of service on principles akin to those of Ford.”

By the time Emanuel Haldeman-Julius died in 1951 — less than a year after Clement Wood died of a stroke — there were 2,300 Little Blue Book titles, 1,800 still in print. Haldeman’s son Henry continued his father’s work until 1978 when the Little Blue Book publishing plant in Girard, Kansas tragically burned down.

Now the books are collector’s items, and although my coverless, yellowed pamphlet is probably barely worth more than the 5 cents it originally cost, it’s a pearl of great price to me because it’s a) awesome, and b) the book my mom read with a flashlight under the covers when she was just a little girl dreaming about her first kiss.

And this, ladies and gentlemen, is why I’m a history nerd. Happy Valentine’s Day, lovahs. :love: