Researchers have found 28 books in 74 volumes from Thomas Jefferson’s last library in the Coolidge collection of St. Louis’ Washington University. This makes Washington University’s library the third largest repository of Thomas Jefferson’s books after the Library of Congress and the University of Virginia. Jefferson sold 6,700 of his books to the Library of Congress after the British burned Washington, D.C. in 1814, and he founded the University of Virginia in 1819, so that’s impressive company for Washington University to keep.

Researchers have found 28 books in 74 volumes from Thomas Jefferson’s last library in the Coolidge collection of St. Louis’ Washington University. This makes Washington University’s library the third largest repository of Thomas Jefferson’s books after the Library of Congress and the University of Virginia. Jefferson sold 6,700 of his books to the Library of Congress after the British burned Washington, D.C. in 1814, and he founded the University of Virginia in 1819, so that’s impressive company for Washington University to keep.

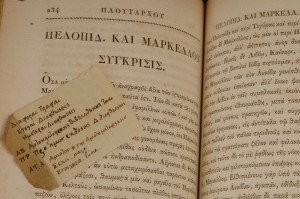

After Jefferson gave the Library of Congress most of his books, he immediately started to collect again. Those 1,600 books he purchased in the last decade of his life are known as the retirement collection, and they were unfortunately scattered in 1829, three years after his death, when his relatives sold them at auction to pay his extensive debts. Researchers at Monticello, Thomas Jefferson’s estate and a National Historic Landmark, have been trying to track down the retirement collection since 2004 so it can be digitized and made available to the public in an online database called Thomas Jefferson’s Libraries.

Endrina Tay, the Thomas Jefferson’s Libraries project manager, found a number of auction catalogs from the 1829 sale, but they didn’t include the names of the buyers. Then she found a letter from Joseph Coolidge, the husband of one of Jefferson’s granddaughters, asking the husband of another Jefferson granddaughter to secure some of the books for him at auction.

Endrina Tay, the Thomas Jefferson’s Libraries project manager, found a number of auction catalogs from the 1829 sale, but they didn’t include the names of the buyers. Then she found a letter from Joseph Coolidge, the husband of one of Jefferson’s granddaughters, asking the husband of another Jefferson granddaughter to secure some of the books for him at auction.

Coolidge wrote Nicholas Philip Trist, who married another Jefferson granddaughter, saying, “If there are any books which have T. J. notes or private marks, they would be interesting to me.” He added, “I beg you to interest yourself in my behalf in relation to the books; remember that his library will not be sold again, and that all the memorials of T. J. for myself and children, and friends, must be secured now! — this is the last chance!”

When Ms. Tay found the letter “C” next to some of the lots in one of the catalogs, she thought those volumes might have been successfully purchased by Coolidge. Then another piece of the puzzle snapped into place.

While [Tay] was tracking down the retirement library, one of her fellow Monticello scholars, Ann Lucas Birle, was researching a book about the Coolidges and, searching Google Books, found a reference in The Harvard Register to a gift in 1880 from a Coolidge son-in-law, Edmund Dwight, to a fellow Harvard alumnus and possible relative, William Greenleaf Eliot, a founder of Washington University.

“It could have been his parents have died, he’s left with 3,000 books, what should he do with these that would really do good?” Dean Baker said. “A great-uncle just founded a new university. If you send them to a university that doesn’t even have 3,000 books, it could make a world of difference.”

Tay and Birle alerted Washington University to their find, and rare books curator Erin Davis and assistant archivist Miranda Rectenwald scoured the rare book collection for all the ones donated by the Coolidge family in 1880, which had long since been dispersed throughout the library’s holdings with no particular indicators of their origin. They used a turn of the century ledger that included a listing of the Coolidge books for reference and were able to track down the Jefferson volumes.

Their work isn’t over yet, though. The curators will continue to examine the Coolidge collection for any more Jefferson books that have escaped notice. University officials are on cloud nine, needless to say. Shirley K. Baker, Washington University’s vice chancellor for scholarly resources and dean of university libraries, enthuses: “It is particularly appropriate that these books should be here in Missouri. It was Jefferson who acquired this land in the Louisiana Purchase, and St. Louis was the jumping-off point for the expedition Jefferson sent to explore the new territory.”