As I was saying before I was so rudely interrupted…

Seneca Village was a vibrant small community founded in 1825 by free working class African-Americans in uptown Manhattan. The area from W82nd to 88th Streets between Seventh and Eighth Avenues (click here for a larger version of the map) was still farmland back then, a good six miles north of teeming downtown and this was long before public transit. Maps of New York City as late as 1840 actually stop at W26th Street, almost four miles south of Seneca Village.

Despite its onerous distance from the city center, the rural location had the marked advantage of offering working class African-Americans, who were subject to the worst living conditions the notoriously crowded, filthy, crime-ridden slums of lower Manhattan had to offer, access to fresh air, space and land, land that they could build homes on and cultivate to support their families. As powerful a motivation as that must have been, it wasn’t the only incentive black people with the financial wherewithal had to purchase their own property.

When Andrew William bought the first three lots of land that would become Seneca Village on September 27, 1825, slavery was still legal in New York. Legislation passed in 1799 determined that enslaved people in the state would be emancipated on July 4, 1827, but there were addenda and provisos, of course, so not everyone was instantly manumitted on the magic date, and even free black men were denied the political rights that had been extended to white men. According to the New York State Constitution of 1821, only African-American males who owned $250 in property had the right to vote. (They also had to prove that they had lived in the state and paid taxes for three years prior to casting their first ballot.) Andrew William paid John and Elizabeth Whitehead $125 for those three lots he purchased; that put him halfway to suffrage.

By 1850, black Seneca Village residents were 39 times more likely to own property than any other African-Americans in New York City. The 1855 census puts the black population of New York City at 12,000. Out of that 12,000 only 100 men qualified for the vote. Ten of them lived in Seneca Village. That’s ten percent of the entire African-American voting population of New York City living in a village of less than 300 people.

Andrew William wasn’t the only one to buy from the Whiteheads on September 27, 1825. The African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church bought six lots near 86th Street to use as a cemetery. One of the AME Zion Church trustees, Epiphany Davis, bought twelve lots for her own use, and a little community was born. The village grew steadily from then on as black people moved out of lower Manhattan or migrated to the city from Virginia, Maryland, Connecticut and New Jersey. The Whiteheads sold at least another 24 lots to African-Americans over the next ten years.

In the 1840s Irish and German immigrants joined the Seneca Village community. By 1855, census and property records put the population of the village at 264, 30% of them European, predominately Irish. One of New York’s most in/famous native sons, George Washington Plunkitt, Tammany Hall politician and homespun philosopher of cheery corruption who “held the offices of State Senator, Assemblyman, Police Magistrate, County Supervisor and Alderman, and who boasts of his record in filling four public offices in one year and drawing salaries from three of them at the same time,” was born to Irish immigrant parents in Seneca Village in 1842.

In the 1840s Irish and German immigrants joined the Seneca Village community. By 1855, census and property records put the population of the village at 264, 30% of them European, predominately Irish. One of New York’s most in/famous native sons, George Washington Plunkitt, Tammany Hall politician and homespun philosopher of cheery corruption who “held the offices of State Senator, Assemblyman, Police Magistrate, County Supervisor and Alderman, and who boasts of his record in filling four public offices in one year and drawing salaries from three of them at the same time,” was born to Irish immigrant parents in Seneca Village in 1842.

By all accounts the diverse community got along peacefully. Black and white worshiped together at the All Angels’ Church and were buried together in its cemetery. The one village midwife, Margaret Geery, delivered African-American babies and Irish and German babies alike.

The map to the right, drawn by Egbert Viele, shows the layout of the Seneca Village ca. 1856. (For your orientation information, Eighth Avenue is on the top and Seventh Avenue and the Receiving Reservoir are on the bottom; 82nd Street is on the left and 86th Street is on the right.) This interactive map of Seneca Village uses Viele’s drawing as a base to explore the layout and demographics of the Village.

The map to the right, drawn by Egbert Viele, shows the layout of the Seneca Village ca. 1856. (For your orientation information, Eighth Avenue is on the top and Seventh Avenue and the Receiving Reservoir are on the bottom; 82nd Street is on the left and 86th Street is on the right.) This interactive map of Seneca Village uses Viele’s drawing as a base to explore the layout and demographics of the Village.

As the population of Manhattan swelled — between 1821 and 1855 the population quadrupled — and the city expanded northward, rural land that had once been considered hinterlands started to feel the pressure. In the late 1830s, residents of a community called York Hill around Sixth Avenue and W42nd Street (next to today’s Bryant Park of New York Fashion Week fame, and the yellow spot on the Google Map) moved to Seneca Village after the government evicted them to build a basin for the Croton Distributing Reservoir, a four-acre lake that played a key role in the first aqueduct system that carried fresh water from upstate New York into the city.

By the 1840s the city was so crowded that people went to cemeteries like Green-Wood in Brooklyn for picnics and carriage rides. Prominent figures like New York Evening Post editor William Cullen Bryant (after whom the above-mentioned Bryant Park would be named) and landscape architect Andrew Jackson Downing argued that New York City needed a public park like Paris’ Bois de Boulogne or London’s Hyde Park. Privileged New Yorkers, keen for a congenial setting to drive their carriages and cut their fine figures, very much agreed.

By the 1840s the city was so crowded that people went to cemeteries like Green-Wood in Brooklyn for picnics and carriage rides. Prominent figures like New York Evening Post editor William Cullen Bryant (after whom the above-mentioned Bryant Park would be named) and landscape architect Andrew Jackson Downing argued that New York City needed a public park like Paris’ Bois de Boulogne or London’s Hyde Park. Privileged New Yorkers, keen for a congenial setting to drive their carriages and cut their fine figures, very much agreed.

Not everyone was on board with the idea. No matter where the proposed park ended up, someone was going to be getting the shaft, and those someones were going to be poor. Social reformer Hal Guernsey said “Will anyone pretend the park is not a scheme to enhance the value of uptown land, and create a splendid center for fashionable life, without regard to, and even in dereliction of, the happiness of the multitude upon whose hearts and hands the expenses will fall?”

Nobody bothered to pretend. The newspapers advocating the new park smeared Seneca Village as a “shantytown” inhabited by “wretched and debased” “squatters.” The fact that they had owned their property and homes for decades made no difference. How could a working class enclave possibly compete with the prospect of a beautiful landscaped urban Eden?

In 1853, the New York legislature picked a spot — 700 acres from 59th to 106th Streets between Fifth and Eighth Avenues — and authorized the taking of the land by eminent domain. They set aside $5 million to buy the land from its current owners, approximately 1,600 people over 7,500 lots, just under 300 of them in Seneca Village. The property owners fought the law. For two years they petitioned the court and appealed decisions trying to save their homes, churches, school, cemeteries, lives. The law won.

In the summer of 1856, Mayor Fernando Wood sent the residents of Seneca Village a final notice and in 1857 he sent the police to bludgeon them out. According to one newspaper, the violent clearing of Seneca Village was a glorious victory that would “not be forgotten [as] many a brilliant and stirring fight was had during the campaign. But the supremacy of the law was upheld by the policeman’s bludgeons.” On October 1, 1857, the city government announced that the land was free of pesky human habitation. The dwellings were demolished and Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux began to build Central Park.

In the summer of 1856, Mayor Fernando Wood sent the residents of Seneca Village a final notice and in 1857 he sent the police to bludgeon them out. According to one newspaper, the violent clearing of Seneca Village was a glorious victory that would “not be forgotten [as] many a brilliant and stirring fight was had during the campaign. But the supremacy of the law was upheld by the policeman’s bludgeons.” On October 1, 1857, the city government announced that the land was free of pesky human habitation. The dwellings were demolished and Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux began to build Central Park.

We don’t know what happened to the people buried in the two Seneca Village cemeteries we know of. There is no record of remains being exhumed and relocated before the park was built. Nor do we know what became of the Senecans who were evicted or if there any descendants of theirs still in the city.

Central Park was indeed an enclave for the wealthy, too far uptown to be convenient for the working class who even after the inception of city rail systems in the late 1860s still couldn’t comfortably afford to use the first public park in the country. All the concerts and events took place Monday through Saturday, so most laborers, who only had Sunday off, could not attend. It wasn’t until the 1920s when the first playground was installed that Central Park began to become a popular spot for working class families.

Central Park was indeed an enclave for the wealthy, too far uptown to be convenient for the working class who even after the inception of city rail systems in the late 1860s still couldn’t comfortably afford to use the first public park in the country. All the concerts and events took place Monday through Saturday, so most laborers, who only had Sunday off, could not attend. It wasn’t until the 1920s when the first playground was installed that Central Park began to become a popular spot for working class families.

As the park grew in popularity, the fate of Seneca Village faded, so much so that until yesterday I didn’t even know it had existed. Some historians knew of it, of course, but they had to content themselves with documentary research and boring the occasional hole to examine the site underneath the park. Central Park is governed by a non-profit conservancy and the conservancy was not willing to allow the area to be excavated.

Just eight weeks ago the Institute for the Exploration of Seneca Village History, after a decade of courteous but consistent inquiries, finally received permission from the Central Park Conservancy to excavate the Seneca Village site. They required that the archaeologists fill in the holes they’d dug and remove their equipment at the end of every day, though, which given what people get up to in Central Park at night, is probably for the best.

Just eight weeks ago the Institute for the Exploration of Seneca Village History, after a decade of courteous but consistent inquiries, finally received permission from the Central Park Conservancy to excavate the Seneca Village site. They required that the archaeologists fill in the holes they’d dug and remove their equipment at the end of every day, though, which given what people get up to in Central Park at night, is probably for the best.

With the help of 10 college interns, the institute focused on two primary sites: the yard of a resident named Nancy Moore, and the home of William G. Wilson, a sexton at All Angels’ Episcopal Church, both of whom were black. Records show that Mr. Wilson and his wife, Charlotte, had eight children and lived in a three-story wood-frame house.

With the help of 10 college interns, the institute focused on two primary sites: the yard of a resident named Nancy Moore, and the home of William G. Wilson, a sexton at All Angels’ Episcopal Church, both of whom were black. Records show that Mr. Wilson and his wife, Charlotte, had eight children and lived in a three-story wood-frame house.

The holes, which were up to six feet deep, revealed stone foundation walls and myriad artifacts, including what appeared to be an iron tea kettle and a roasting pan (now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art for conservation), a stoneware beer bottle and fragments of Chinese export porcelain. […]

The former yard of Nancy Moore contained the original soil of Seneca Village, in contrast to Mr. Wilson’s property, which appeared to have been dug up and filled during the park’s construction. Thus, in Ms. Moore’s yard, the interns found a number of items that might have been discarded, including fragments of two clay pipes, as well as bones from animals that had been butchered.

The former yard of Nancy Moore contained the original soil of Seneca Village, in contrast to Mr. Wilson’s property, which appeared to have been dug up and filled during the park’s construction. Thus, in Ms. Moore’s yard, the interns found a number of items that might have been discarded, including fragments of two clay pipes, as well as bones from animals that had been butchered.

The artifacts testify to what a well-established, stable community Seneca Village was, and there is a lot more to be discovered. The excavation ends on Friday, but the Institute has 250 bags of material to analyze, including soil samples that will tell us about the environment at the time and what plants people grew for food and fun.

The Institute will hold an open house on the site on August 24th, so if you’re in town go check it out. Otherwise, you can explore panoramic pictures of the excavation on the Seneca Village Project website.

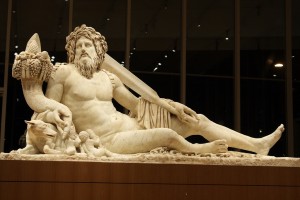

There is a small street in the Campo Marzio neighborhood of Rome’s historic center called Via del Pie’ di Marmo, or Marble Foot Way. It is named after a large marble foot perched on the side of the street that is all that remains of a colossal statue. This one foot is four feet long, so the statue it used to be a part of would have been something like 26 feet high.

There is a small street in the Campo Marzio neighborhood of Rome’s historic center called Via del Pie’ di Marmo, or Marble Foot Way. It is named after a large marble foot perched on the side of the street that is all that remains of a colossal statue. This one foot is four feet long, so the statue it used to be a part of would have been something like 26 feet high.

Exposed to filth, pollution and a shoddy restoration that left the poor giant foot with a huge grey plaster gash marring its arch, the sculpture was nonetheless voted one of Rome’s “places of the heart” last year, and is a favorite both of locals and tourists. Last month, as part of an effort to restore some of Rome’s many outdoor sculptures, several of them of the famous talking variety, the Pie’ di Marmo was removed from its eponymous street, thoroughly cleaned and returned. It has a nice new gate around the pedestal and everything.

Exposed to filth, pollution and a shoddy restoration that left the poor giant foot with a huge grey plaster gash marring its arch, the sculpture was nonetheless voted one of Rome’s “places of the heart” last year, and is a favorite both of locals and tourists. Last month, as part of an effort to restore some of Rome’s many outdoor sculptures, several of them of the famous talking variety, the Pie’ di Marmo was removed from its eponymous street, thoroughly cleaned and returned. It has a nice new gate around the pedestal and everything.