Queen Elizabeth I was a dedicated and accomplished equestrian. She loved to hawk and hunt, and she took regular high speed rides over long distances well into her sixties. So hardcore a rider was she that she had horses imported from Ireland because her English ones weren’t fast or tough enough to withstand her usage. She rode both sidesaddle and astride, and could literally go all day, far outpacing her ladies.

Queen Elizabeth I was a dedicated and accomplished equestrian. She loved to hawk and hunt, and she took regular high speed rides over long distances well into her sixties. So hardcore a rider was she that she had horses imported from Ireland because her English ones weren’t fast or tough enough to withstand her usage. She rode both sidesaddle and astride, and could literally go all day, far outpacing her ladies.

It wasn’t just for exercise and fun. Her skill on horseback could be a powerful symbol of masculinity and strength as the equestrian statue had been a traditional representation of gods, heroes, kings and military leaders since at least Ancient Greece. Elizabeth was keenly aware of that and used it to her advantage, most famously at Tillbury in 1588 where she wore a silver armour chestplate and delivered a rousing gender-bending speech on horseback to her army amassed to defend against a potential land invasion from the Spanish Armada.

I know I have the body of a weak and feeble woman, but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and a king of England too, and think foul scorn that Parma or Spain, or any prince of Europe should dare to invade the borders of my realm; the which, rather than any dishonour shall grow by me, I myself will take up arms, I myself will be your general, judge, and rewarder of every one of your virtues in the field.

She also tapped into that symbol on occasions where the purpose was statesmanship rather than military. Every summer when London became unbearably hot, stinky and disease-ridden, the entire court would leave town and travel to different places around the country. Local nobles would have to foot the bill to host the Queen and her household, and towns would also spend masses of money to spruce themselves up for the royal visit. They also had to scare up some cash since a gift of moneys to the queen was traditional.

She also tapped into that symbol on occasions where the purpose was statesmanship rather than military. Every summer when London became unbearably hot, stinky and disease-ridden, the entire court would leave town and travel to different places around the country. Local nobles would have to foot the bill to host the Queen and her household, and towns would also spend masses of money to spruce themselves up for the royal visit. They also had to scare up some cash since a gift of moneys to the queen was traditional.

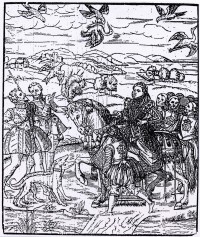

These visits were known as royal progresses, the ceremonial entry of a ruler into a town accompanied by processions, orations, ritual exchanges, mock battles and festivities that went on for several days. Elizabeth didn’t invent them, although she did become particularly known for them. Influenced by revived knowledge of Roman triumphs, royal progresses underscored the authority of the sovereign, the fealty owed to her by her subjects and the benevolent favor she bestowed upon them in return. The ruler approaching the city gates on horseback, escorted by a retinue on horseback and greeted by town dignitaries on horseback were key symbolic elements of the pageantry. Queens were also transported on litters to and beyond the city gates, and Elizabeth did this on occasion, but most of the time she rode her horse just as her father and her father’s father had done.

In 1574, the seafaring merchant city of Bristol was chosen for a summer progress. There was supposed to have been one four years earlier, but as time came close the city scrambled to clean up the roads near Newgate so the Queen’s large household could approach in comfort and safe from brigands. After they spent the money and repaired the roads, they found the Queen had changed her plans. They went all out, therefore, to make sure the 1574 royal visit went off without a hitch. The city corporation spent a grand total of £1,053 on preparations and supplies like sand to level the roads, cannon and two tons of gunpowder for salutes and battles, 400 infantry men and their uniforms. That works out to £183,106.17 today (bless the UK National Archives’ online historical currency converter), close to $300,000 for three days’ visit. The human cost was even greater. Ten men died and as many again suffered severe burns in gunpowder explosions the day before the Queen get there.

Here is her arrival described in Adams’s Chronicle of Bristol from 1623:

The High Crosse was new painted and gilded ; and on the 14th of August 1574 our gracious Queene Elizabeth came to this city. The mayor and all the council, riding upon good steeds, with footcloth, and pages by their sides, went to meet and received her Majesty within Lafford’s gate, where the mayor delivered the gilt mace unto Her Grace and she delivered it unto him again. And so the mayor rested kneeling before Her Grace whiles Mr. John Popham, esquire, and Recorder of this city, made an oration unto the Queene, which being ended he stood up and delivered a fair needlework purse wrought with silk and gold unto her Majesty, with 100£ in gold therein : then the mayor and his brethren took their horses, the mayor himself rode nigh before the Queene, between 2 Serjeants at arms, and the rest of the council rode next before the nobility and trumpeters, and so passed through the city….

The exchange of the mace is notable because it symbolized the town handing over its authority to the Queen and receiving it back as a gift of her graciousness. When Henry VII rode into town to assert his authority and establish relations with the city after the Battle of Bosworth, there was no exchange of the mace. The mayor kept it. The King’s visit acknowledged the town’s independence and self-government. By Queen Elizabeth’s time, things had drastically changed. The Tudor/Stuart foray into absolute monarchy would come to a (decapitated) head 80 years later in the English Civil War.

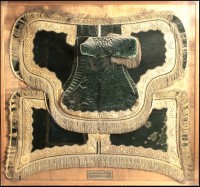

After the three days of sea battles and fort assaults, the Queen made five knights, tipped the band, and gave an elaborate quilted emerald green velvet and gold fringed saddlecloth that she had used during her visit to one of her hosts. Elizabeth had just months before enacted sumptuary laws prohibiting the wearing of velvet and gold by anyone except for a small group of aristocrats, so this was a luxurious gift indeed. The descendants of that host kept the saddlecloth in exceptionally good condition for the next 438 years, later mounting it in wood and glass for display.

After the three days of sea battles and fort assaults, the Queen made five knights, tipped the band, and gave an elaborate quilted emerald green velvet and gold fringed saddlecloth that she had used during her visit to one of her hosts. Elizabeth had just months before enacted sumptuary laws prohibiting the wearing of velvet and gold by anyone except for a small group of aristocrats, so this was a luxurious gift indeed. The descendants of that host kept the saddlecloth in exceptionally good condition for the next 438 years, later mounting it in wood and glass for display.

I’m not sure how it was used. I wouldn’t have thought it was a saddlecloth as in a blanket that goes underneath a saddle because it has a puffy backrest. It can’t be a saddle, though some articles have called it so, because it has no ties, no stirrups, nothing at all that would keep a person attached to a moving beast. Maybe a sidesaddle pillion? If so, it’s missing a pommel and I can’t see Elizabeth riding demurely behind a man in an actual saddle on an official royal visit. Maybe the puffy part just went behind the saddle backrest as additional support. Or could it have been worn on top of the saddle? Its segmented design would make it fall well around something underneath and there’s a slit in the front center that a pommel could slide through.

Anyway, the last descendant to own it was Miles Kington, a humorist and author best known for his series of Let’s Parler Franglais books which I fondly recall lolling at when I was a kid.

Anyway, the last descendant to own it was Miles Kington, a humorist and author best known for his series of Let’s Parler Franglais books which I fondly recall lolling at when I was a kid.

Miles once revealed in a fax to his wife Caroline the dark secret behind the Kington Saddle. I’m quoting the whole thing even though this entry is already ludicrously verbose because it’s awesome. Consider it payoff for having read this far.

My dear Caroline

I sometimes worry that i may pass on to the other side before i have handed down to you the secret of the KINGTON SADDLE. Ridiculous, i know, as the doctor has said given reasonable treatment and a visit to the pub every now and then, there’s no reason why i shouldn’t last another 40 years, but nevertheless i think perhaps the time has come to tell the dread secret of the KINGTON SADDLE.

But it’s just a silly old priceless family heirloom sitting in an old glass case, i hear you laugh. There’s nothing secret about it at all…….Ah, would that be so. But this KINGTON SADDLE has been handed down through eight or nine of, maybe seventeen generations of the Kington family, all of whom are now dead. Yes, every single previous owner of the KINGTON SADDLE is now in another place, and it’s not Saudi Arabia, i’m talking about. Why do you think they were all struck down before they reached 100? Why do you think nobody ever gets the KINGTON SADDLE out and rides around on it on a horse? Why, above all, do you think nobody even wants to have it in their house, and everyone whispers furtively: “Let’s give it to cousin Laurence….. Let’s put it in a museum…..”?

I’ll tell you.

It’s because of the curse of the KINGTON SADDLE. The curse which has scattered the family far afield, from Wrexham to London, from London to Bath, and from Bath to a crazy steam railway between Keighley and Haworth only five miles long, for God’s sake. As a child i remember getting a really nasty sore throat and my father leaning over my bed and saying, “The curse of the KINGTON SADDLE has got him, we must apply the only know antidote, mother, give me a corkscrew” – yes, at the age of ten my life was saved by red wine and i have never looked back since, but that is another story.

I am surprised you have never noticed that none of the Kingtons ever rides a horse. There is a good reason for this. None of us can ever ride a horse because of the secret of the KINGTON SADDLE, and were any of us to mount a horse, it would mean instant death. For the horse. My grand-father, Major Kington, mounted a horse for the regimental race in 1907. It collapsed on the starting-line and my grand-mother lost a lot of money. My great-great-grandfather Colonel Kington took part in the charge of the Light Brigade, and had not gone 5 yards before his mount keeled over, dead, badly creasing his trousers. My great-great great

CONTINUED SOON

Sadly, the curse struck again and Miles passed away in 2008 of pancreatic cancer long before he turned 100. Now the saddlecloth is going up for auction at Dreweatts’ Arms, Medals & Militaria sale on September 26th. The explanatory fax is included in the lot. The estimated sale price is £8,000-10,000 ($13,000-$16,000). For something that once hoisted Queen Elizabeth I’s fundament on a momentous occasion and that comes with such a charming history written by a famous humorist, that seems a modest price range.

Sadly, the curse struck again and Miles passed away in 2008 of pancreatic cancer long before he turned 100. Now the saddlecloth is going up for auction at Dreweatts’ Arms, Medals & Militaria sale on September 26th. The explanatory fax is included in the lot. The estimated sale price is £8,000-10,000 ($13,000-$16,000). For something that once hoisted Queen Elizabeth I’s fundament on a momentous occasion and that comes with such a charming history written by a famous humorist, that seems a modest price range.