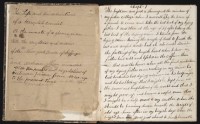

A manuscript at Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library has been authenticated as the prison memoir of 19th century African-American inmate Austin Reed. Finding a previously-unknown Black writer from the before the Civil War is extremely rare, and this work stands out as the earliest prison memoir ever written by an African-American (that we know of). A rare book dealer purchased the notebook and two sewn folios at an estate sale Rochester, western New York state, some years ago. The family selling it had no information about it other than it had been in their family for as long as anyone could remember. The Beinecke bought it from the dealer in 2009 and set about researching the 304-page memoir and its author.

A manuscript at Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library has been authenticated as the prison memoir of 19th century African-American inmate Austin Reed. Finding a previously-unknown Black writer from the before the Civil War is extremely rare, and this work stands out as the earliest prison memoir ever written by an African-American (that we know of). A rare book dealer purchased the notebook and two sewn folios at an estate sale Rochester, western New York state, some years ago. The family selling it had no information about it other than it had been in their family for as long as anyone could remember. The Beinecke bought it from the dealer in 2009 and set about researching the 304-page memoir and its author.

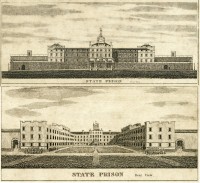

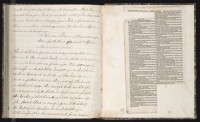

The unpublished book is entitled The Life and Adventures of a Haunted Convict, or the Inmate of a Gloomy Prison by Rob Reed and it’s an autobiography of Reed’s experiences in the criminal justice system from the 1830s to the 1850s. Most of that time he served for theft at Auburn Prison, the second state prison in New York and the oldest prison in the country still in use today. The traditional horizontal black and white striped prison uniform was invented at Auburn, and the first electric chair execution took place there in 1890.

The unpublished book is entitled The Life and Adventures of a Haunted Convict, or the Inmate of a Gloomy Prison by Rob Reed and it’s an autobiography of Reed’s experiences in the criminal justice system from the 1830s to the 1850s. Most of that time he served for theft at Auburn Prison, the second state prison in New York and the oldest prison in the country still in use today. The traditional horizontal black and white striped prison uniform was invented at Auburn, and the first electric chair execution took place there in 1890.

Built in 1816, Auburn Prison was relatively new when Reed was a guest. Its approach was novel because the focus was on rehabilitation, but the Auburn System, as it became known, was hardly touchy-feely. The aim was instill dedication to work and responsibility by breaking down prisoners’ sense of self and community with other inmates. Prisoners had to work for at least 10 hours a day, to live in solitary confinement when not working, to march in lockstep exactly one arm’s width from each other while looking at the side and never looking at the guards or other inmates, and to observe complete silence at all times.

Punishments for violations of the rules including floggings with whips and cat-o-nine-tails, the “shower bath,” an elaborate form of waterboarding, and the “yoke,” a 40-pound bar of iron attached to the back of the prisoner’s neck and both hands.

Punishments for violations of the rules including floggings with whips and cat-o-nine-tails, the “shower bath,” an elaborate form of waterboarding, and the “yoke,” a 40-pound bar of iron attached to the back of the prisoner’s neck and both hands.

Reed’s memoir was intended to introduce a curious public to life in the new institution – the solitary cells, the dining hall and the hospital, the work to be done in the various workshops, and regulations for inmate conduct. Reed’s account also aimed to expose the unusual and brutal punishments inflicted on dissenters, and he made a pointed comparison between New York prisons and the slaveholding South.

“The Reed prison narrative manuscript is a revelation. Nothing quite like it exists,” says Blight. “Reed is a crafty and manipulative storyteller, and perhaps above all he left an insider’s look at the American world of crime, prisons, and the brutal state of race relations in the middle of the 19th century.”

Yale English professor Caleb Smith worked with Beinecke archivists and Christine McKay, a genealogical researcher at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, to research Austin Reed and authenticate the manuscript. Using newspaper articles, court records and prison files, they were able to identify “Rob Reed” as Austin Reed, a free Black man born near Rochester. He was in trouble with the law from an early age and spent time in the House of Refuge in Manhattan, a reformatory school where he learned to read and write. It was a letter Reed wrote to the warden of the House of Refuge that linked Austin Reed to his nom de plume. In it, he gives some of his background and asks whether the House has kept any of his juvenile records. He was researching his youth, apparently, to include in the memoir.

Yale English professor Caleb Smith worked with Beinecke archivists and Christine McKay, a genealogical researcher at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, to research Austin Reed and authenticate the manuscript. Using newspaper articles, court records and prison files, they were able to identify “Rob Reed” as Austin Reed, a free Black man born near Rochester. He was in trouble with the law from an early age and spent time in the House of Refuge in Manhattan, a reformatory school where he learned to read and write. It was a letter Reed wrote to the warden of the House of Refuge that linked Austin Reed to his nom de plume. In it, he gives some of his background and asks whether the House has kept any of his juvenile records. He was researching his youth, apparently, to include in the memoir.

“The Reed manuscript is an astonishing discovery and a unique resource documenting the lives of African-American prisoners in antebellum America,” says Nancy Kuhl, curator of poetry for the Yale Collection of American Literature. “Handwritten manuscripts of novels and memoirs by 19th-century African Americans remain extraordinarily rare. The Reed manuscript significantly enriches the canon of 19th-century African-American Literature and deepens our understanding of all 19th-century America.”

The memoir never made it into print, despite Reed’s clear intention that it be published, but that will soon change. Caleb Smith is preparing an annotated version of the manuscript for print. Meanwhile, the Beinecke Library has scanned and uploaded every page of the notebook and folios. You can view them here. The handwriting is impressively legible. There are grammatical and spelling errors, but nothing that makes it hard to read.

The memoir never made it into print, despite Reed’s clear intention that it be published, but that will soon change. Caleb Smith is preparing an annotated version of the manuscript for print. Meanwhile, the Beinecke Library has scanned and uploaded every page of the notebook and folios. You can view them here. The handwriting is impressively legible. There are grammatical and spelling errors, but nothing that makes it hard to read.