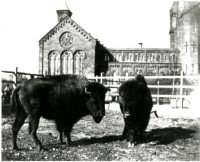

You may have seen the famous picture of American bison who lived behind the Smithsonian Castle on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. in the late 19th century. I posted it a few years ago when the Castle was damaged in an earthquake just because it’s such a charming image. What I didn’t realize at the time is that those incongruously located bison played a pivotal role in the creation of the National Zoo.

You may have seen the famous picture of American bison who lived behind the Smithsonian Castle on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. in the late 19th century. I posted it a few years ago when the Castle was damaged in an earthquake just because it’s such a charming image. What I didn’t realize at the time is that those incongruously located bison played a pivotal role in the creation of the National Zoo.

In 1886, the Smithsonian’s chief taxidermist William Temple Hornaday spent three months taking a census of bison numbers by corresponding with ranchers, hunters, zookeepers, and military officers all over the country. It was widely known that the situation was dire, that all the great herds were gone, indiscriminately slaughtered by hunters, that from the 10-15 million that once roamed the range, maybe a few thousand individuals remained in the more inaccessible regions of the northern range. Hornaday’s research found that extinction loomed even closer, that instead of thousands there were probably fewer than 300 head of wild bison left in the entire United States.

In 1886, the Smithsonian’s chief taxidermist William Temple Hornaday spent three months taking a census of bison numbers by corresponding with ranchers, hunters, zookeepers, and military officers all over the country. It was widely known that the situation was dire, that all the great herds were gone, indiscriminately slaughtered by hunters, that from the 10-15 million that once roamed the range, maybe a few thousand individuals remained in the more inaccessible regions of the northern range. Hornaday’s research found that extinction loomed even closer, that instead of thousands there were probably fewer than 300 head of wild bison left in the entire United States.

Spencer F. Baird, Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, concerned that the National Museum only had a handful of ratty skins, a skeleton, a couple of heads and assorted bones in its collection, agreed to send Hornaday on a mission to secure enough specimens before there were none left to be had. Hornaday’s brief was to kill between 80 and 100 bison, possibly a third of the entire surviving population, to ensure the Smithsonian, smaller museums and future museums not yet in existence would have specimens to display and study when the bison were extinct.

Spencer F. Baird, Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, concerned that the National Museum only had a handful of ratty skins, a skeleton, a couple of heads and assorted bones in its collection, agreed to send Hornaday on a mission to secure enough specimens before there were none left to be had. Hornaday’s brief was to kill between 80 and 100 bison, possibly a third of the entire surviving population, to ensure the Smithsonian, smaller museums and future museums not yet in existence would have specimens to display and study when the bison were extinct.

This is a passage from a letter Hornaday wrote to Baird in December of 1886 reporting on the team’s success:

This is a passage from a letter Hornaday wrote to Baird in December of 1886 reporting on the team’s success:

I consider that we have been extremely lucky in finding a sufficient number of buffalo where it was supposed by people generally that none existed. Our “outfit” has been pronounced by old buffalo hunters “The luckiest outfit that ever hunted buffalo in Montana,” and the opinion is quite generally held that our “haul” of specimens could not be equaled again in Montana by anybody, no matter what their resources for the reason that the buffalo are not there. We killed very nearly all we saw and I am confident there are not over thirty-head remaining in Montana, all told. By this time next year the cowboys will have destroyed about all of this remnant. We got in our Exploration just in the nick of time, — the last day in the evening, so to speak, and I do not hesitate to say that I am really rejoiced over the fact that we have been successful in securing the specimens we needed so urgently.

I understand his perspective — hunters would have killed those bison anyway, so this way they were preserved for posterity at least — but my modern sensibilities can’t help but find the impulse to conserve by destruction contradictory.

William Temple Hornaday didn’t stop there, however. He became a powerful advocate for the wild bison, realizing he had to at least try to prevent the total annihilation of the noble beast. He actually brought back a live bison, a calf he named Sandy, from his 1886 hunt, but Sandy only lived a few months. Hornaday got the idea for a national zoo and wrote to Baird proposing it. Baird was very ill and would soon pass away, so his assistant Professor George Brown Goode, appointed acting secretary until a permanent replacement could be found, picked up the mantle.

William Temple Hornaday didn’t stop there, however. He became a powerful advocate for the wild bison, realizing he had to at least try to prevent the total annihilation of the noble beast. He actually brought back a live bison, a calf he named Sandy, from his 1886 hunt, but Sandy only lived a few months. Hornaday got the idea for a national zoo and wrote to Baird proposing it. Baird was very ill and would soon pass away, so his assistant Professor George Brown Goode, appointed acting secretary until a permanent replacement could be found, picked up the mantle.

In the fall of 1887, Goode created the Department of Living Animals of the National Museum and made Hornaday its curator. Their plan was to test the public’s interest in a zoo in the capital. If people were into the test run, getting the necessary legislation passed for a full-on national zoo would be much more likely. Hornaday went off on another field trip to assemble some actual living animals and came back with 15 American natives: one cinnamon bear, one white-tailed deer, one Columbia black-tailed deer, five prairie dogs, a Cross fox, a mule deer, two badgers, a red fox, and two spotted lynx. He set up a rather rickety group of paddocks and sheds on the National Mall and Field of Dreams-like, people came.

In the fall of 1887, Goode created the Department of Living Animals of the National Museum and made Hornaday its curator. Their plan was to test the public’s interest in a zoo in the capital. If people were into the test run, getting the necessary legislation passed for a full-on national zoo would be much more likely. Hornaday went off on another field trip to assemble some actual living animals and came back with 15 American natives: one cinnamon bear, one white-tailed deer, one Columbia black-tailed deer, five prairie dogs, a Cross fox, a mule deer, two badgers, a red fox, and two spotted lynx. He set up a rather rickety group of paddocks and sheds on the National Mall and Field of Dreams-like, people came.

The Smithsonian’s mini-zoo was an instant success. Crowds flocked to see the live animals, and donors from President Grover Cleveland (he donated a golden eagle that had been given to him as a Christmas gift) to wealthy collectors quickly increased the complement of animals. In December of 1887, Hornaday wrote to Goode proposing that they obtain a nucleus of a bison herd to breed them in captivity without diluting the genes by mating them with domestic cattle (something that had been happening on ranches for years) or damaging the line by in-breeding.

In view of the fact that thus far this government has done nothing to preserve alive any specimens of the American Bison, the most striking and conspicuous species on this continent, I have the honor to propose that the Smithsonian Institution, or the National Museum, one or both, take immediate steps to procure either by gift or purchase, as may be necessary, the nucleus of a herd of live buffaloes. Having been spared the misfortune, thanks to the Smithsonian Institution, of being left without a series of skins and skeletons of the species suitable for the wants of the National Museum, it now seems necessary for us to assume the responsibility of forming and preserving a herd of live buffaloes which may, in a small measure, atone for the national disgrace that attaches to the heartless and senseless extermination of the species in a wild state.

To purchase the nucleus herd would be expensive, and space was going to be an issue sooner rather than later. Hornaday’s dream would become closer to reality shortly when frontier surgeon and Indian Agent Dr. Valentine Trant McGillycuddy donated a breeding pair of bison and two of their calves (one male, one female). That wasn’t enough for a breeding program, but it was a great start.

By the spring of 1888, the Department of Living Animals of the National Museum had 172 animals in its charge. The paddocks and shanties around the Smithsonian Castle could not handle the burgeoning population, and Hornaday turned his considerable energies to Congress. A Senate bill was drafted in May of 1888 proposing that $200,000 be spent buying 166 acres of Rock Creek Park for a national zoo. Hornaday testified before the House Appropriations Committee, and although his testimony was well received, a few squeaky wheels had a problem with the proposed bill. Democrat Thomas Stockdale of Mississippi told the press that a national zoo “would be of no use to the poor who come to Washington to visit the last of the buffaloes,” and the idea “does not sound like republicanism. It echoes like royalty.” The bill was defeated soundly with 36 votes in favor, 56 against and one abstention.

By the spring of 1888, the Department of Living Animals of the National Museum had 172 animals in its charge. The paddocks and shanties around the Smithsonian Castle could not handle the burgeoning population, and Hornaday turned his considerable energies to Congress. A Senate bill was drafted in May of 1888 proposing that $200,000 be spent buying 166 acres of Rock Creek Park for a national zoo. Hornaday testified before the House Appropriations Committee, and although his testimony was well received, a few squeaky wheels had a problem with the proposed bill. Democrat Thomas Stockdale of Mississippi told the press that a national zoo “would be of no use to the poor who come to Washington to visit the last of the buffaloes,” and the idea “does not sound like republicanism. It echoes like royalty.” The bill was defeated soundly with 36 votes in favor, 56 against and one abstention.

So the Smithsonian’s Mall zoo had to keep making do for the foreseeable future. In December of 1888, they were forced to decline a most wonderful offer from Buffalo Bill Cody of 18 bison, the third largest private collection in the world, because they didn’t have the room for them. The tragic loss proved to be a public relations victory for the zoo since everyone was bummed at the missed opportunity. Three months later, on March 2, 1889, Grover Cleveland signed the bill establishing a National Zoo which had passed the House by a vote of 131 to 98.

So the Smithsonian’s Mall zoo had to keep making do for the foreseeable future. In December of 1888, they were forced to decline a most wonderful offer from Buffalo Bill Cody of 18 bison, the third largest private collection in the world, because they didn’t have the room for them. The tragic loss proved to be a public relations victory for the zoo since everyone was bummed at the missed opportunity. Three months later, on March 2, 1889, Grover Cleveland signed the bill establishing a National Zoo which had passed the House by a vote of 131 to 98.

That wasn’t the end of the struggle. Hornaday had to fight for his vision against his new boss, Samuel Pierpont Langley, and for funding with Congress. He secured the funding, but he couldn’t persuade Langley to go along with his plans for how the zoo should be designed and operated (Hornaday wanted naturalistic enclosures that flowed with the landscape, two entrances, full public access; Langley did not). Hornaday resigned later in 1889 but kept on fighting for the conservation of the bison. His passionate advocacy took published form in his highly influential 1889 book The Extermination of the American Bison. The National Zoo opened to the public on April 30th, 1891.

That wasn’t the end of the struggle. Hornaday had to fight for his vision against his new boss, Samuel Pierpont Langley, and for funding with Congress. He secured the funding, but he couldn’t persuade Langley to go along with his plans for how the zoo should be designed and operated (Hornaday wanted naturalistic enclosures that flowed with the landscape, two entrances, full public access; Langley did not). Hornaday resigned later in 1889 but kept on fighting for the conservation of the bison. His passionate advocacy took published form in his highly influential 1889 book The Extermination of the American Bison. The National Zoo opened to the public on April 30th, 1891.

Five years later, William Temple Hornaday got another chance to build a zoo from the ground up. The New York Zoological Society appointed him creator and director of what would become the Bronx Zoo. He remained its director until 1926. He continued to lobby tirelessly for the conservation of the American bison and for other endangered species. Today there are 30,000 bison in conservation herds in national parks, zoos and protected areas. There are half a million in commercial herds.

Five years later, William Temple Hornaday got another chance to build a zoo from the ground up. The New York Zoological Society appointed him creator and director of what would become the Bronx Zoo. He remained its director until 1926. He continued to lobby tirelessly for the conservation of the American bison and for other endangered species. Today there are 30,000 bison in conservation herds in national parks, zoos and protected areas. There are half a million in commercial herds.

Now, 125 years after their impending extinction drove the creation of a national zoo, American bison are back at the National Zoo.

[youtube=http://youtu.be/i3aeyWc4usY&w=430]