In 2014, the University of Toronto’s Thomas Fisher Rare Books Library received a donation of medieval and early modern charters from private collector Eric Robertson who had bought them in an Edinburgh book store decades ago. There are 60 charters in the collection, all from the Fleming family of Biggar in the South Highlands of Scotland dating between the 14th and the 17th centuries.

The Fleming family played an important role in medieval Scottish history. Flemish knights and merchants came to Britain from Flanders as early in the 11th century. The Flemings of Biggar are thought to have descended from a knight who was given lands in Devonshire by William the Conqueror. Some Flemish knights fought for King Stephen during the upheavals of the Anarchy. When Henry II came to the throne, the Flemings who had been on Stephen’s side were banished and found refuge in Scotland under King David I (reigned 1124 – 1153). The first Fleming of this family recorded in Scotland was Baldwin Le Fleming who settled in Biggar and was appointed Sheriff of Lanarkshire by David I. As sheriff he controlled the Upper Clyde Valley which was of great strategic importance as the gateway to Scotland for any number of hostile invaders. Baldwin served under two more kings after David — his grandsons Malcolm IV and King William the Lion.

The Fleming holdings expanded significantly in the 14th century when Robert Fleming was granted the fiefdom of Cumbernauld in Dunbartonshire by Robert the Bruce. It was a reward for Fleming’s involvement in one of the era’s most notorious incidents: when Robert the Bruce stabbed John “Red” Comyn, his main competition for the throne of Scotland, to death in the church of the Greyfriars in Dumfries on February 10th, 1306. Fleming reputedly decapitated Red Comyn and presented the head to the Bruce telling him “Let the deid shaw,” meaning “Let the deed show.” That phrase became the Fleming family motto thereafter.

Robert Fleming died shortly thereafter, but his son Malcolm would benefit even more directly from Red Comyn’s death. Robert the Bruce granted him the barony of Kirkintilloch which had belonged to Comyn. The Flemings held Cumbernauld Castle until Cromwell destroyed it in 1650, and along the way gained and lost or sold a number of properties and associated titles. Flemings continued to be closely linked to generations of Scottish monarchs. Much of this history survives in the form of charters, most of them land grants, and the Fleming family collection includes many kings and queens — David II, Robert III, James III, James IV, Charles II, Mary, Queen of Scots — as parties to the charters.

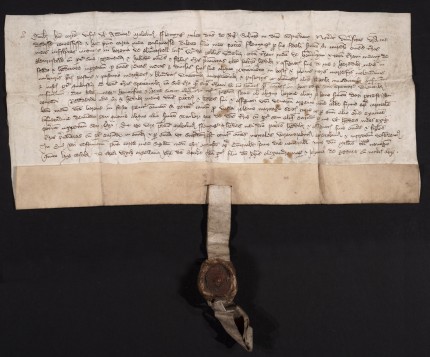

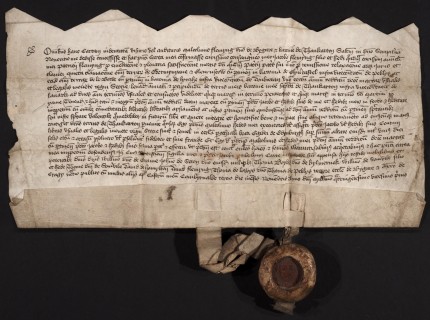

The charters, written in Latin and many still bearing the wax seals of their signers, had not been studied, translated or published before Robertson donated them. The Fisher Library is making up for lost time by digitizing and researching the charters. Once the documents are scanned, the library is sending high resolution images to the University of St Andrews Institute of Scottish Historical Research where researchers can translate and study them.

The first two charters sent to the University of St Andrews have already proved intriguing. The earliest of them dates to 1395 and grants to Patrick Fleming, younger son of Sir Malcolm Fleming of Biggar, the lands of Glenrusto and Over Menyean in the Tweed valley. The second is dated November 3rd, 1421, and transfers property from Malcolm Fleming, grandson of the Malcolm party to the 1395 grant, to his cousin James, son of the Patrick who was the other party to the 1395 grant. Gelnrusto and Over Menyean are two of the properties transferred to James.

This may seem like the dry business of a large family with a vast feudal estate, but the 1421 charter is unusual in that it is part of an indenture. The cutouts along the top of the document are the equivalent of an anti-forging watermark today. Both parties to the indenture would have copies with uneven edges, preventing one of the parties from forging a document that gave them some advantage. What makes the mark of indenture noteworthy in this case is that this type of contract was employed when there were disputes, not in simple transfers of property between family members.

Comparing this document to an inventory of charters in the National Library of Scotland reveals the hidden machinations and violence behind this intrafamily land transfer.

At the same time as receiving this grant, James Fleming made a separate formal resignation of the lands referred to in the charter to his cousin. This included a penalty clause: should James, at a later date, quarrel with Malcolm over the latter’s rights to these lands, James was bound to surrender another estate, Monicabo in Aberdeenshire. This clause is a strong pointer to the fact that what was going on in November 1421 was no simple property deal but involved a degree of coercion of the lesser man, James Fleming, by his more powerful cousin.

Direct evidence of the extent of this coercion is provided by a final document. This is a copy of what is described in the inventory as a ‘writ’, a suitably vague term. In this, James Fleming clears Malcolm Fleming of Biggar and his accomplices of any part in the death of his father, Patrick Fleming, and agrees to end any hostility towards Malcolm. This document would obviously repay further examination but even this record makes clear that the land transactions were associated with the killing of their previous holder. It is surely not a huge stretch to suggest that Patrick Fleming had been killed in a dispute over his estates and that, after his death, his son was being forced to surrender the lands in question to a man implicated in the killing.

Malcolm had all the cards in this relationship. He was the head of the family and had supporters in the highest echelons of power. James had to take this land settlement and its confidentiality clause forcing him to keep his mouth shut about the shady circumstances surrounding his father’s demise or he’d wind up empty-handed and very probably as dead as his father.

Researchers hope that as the digitization of the Robertson Collection continues, more of this story and other unexplored facets of Scottish history will be revealed.