The Arch of Titus which still stands today at the end of the Via Sacra next to the Roman Forum, famous for its period depiction of spoils from the capture of Jerusalem in 70 A.D., is an honorific arch commemorating the emperor’s greatest deeds and apotheosis, not a triumphal arch. Built by his brother Domitian in 82 A.D., the year after Titus’ death and deification, it’s often called a triumphal arch because of the high relief depictions of Roman soldiers carrying the treasures of the Second Temple — the seven-branched Menorah, the silver trumpets, the Table of the Shew Bread — in Titus’ triumphal procession of 71 A.D.

The Arch of Titus which still stands today at the end of the Via Sacra next to the Roman Forum, famous for its period depiction of spoils from the capture of Jerusalem in 70 A.D., is an honorific arch commemorating the emperor’s greatest deeds and apotheosis, not a triumphal arch. Built by his brother Domitian in 82 A.D., the year after Titus’ death and deification, it’s often called a triumphal arch because of the high relief depictions of Roman soldiers carrying the treasures of the Second Temple — the seven-branched Menorah, the silver trumpets, the Table of the Shew Bread — in Titus’ triumphal procession of 71 A.D.

That’s just one motif, however. The central panel in the single arch’s soffit relief depicts Titus being carried to the heavens by an eagle. The inscription also emphasizes the recently deceased emperor’s divinity: “SENATUS/ POPULUSQUE ROMANUS/ DIVO TITO DIVI VESPASIANI F(ilio)/ VESPASIANO AUGUSTO” (The Senate and People of Rome [dedicate this arch] to the divine Titus Vespasian Augustus, son of the divine Vespasian).

That’s just one motif, however. The central panel in the single arch’s soffit relief depicts Titus being carried to the heavens by an eagle. The inscription also emphasizes the recently deceased emperor’s divinity: “SENATUS/ POPULUSQUE ROMANUS/ DIVO TITO DIVI VESPASIANI F(ilio)/ VESPASIANO AUGUSTO” (The Senate and People of Rome [dedicate this arch] to the divine Titus Vespasian Augustus, son of the divine Vespasian).

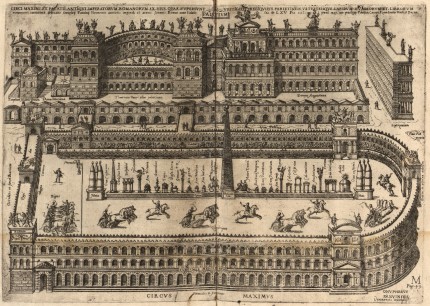

Titus’ real triumphal arch was erected in 81 A.D., the year he died, at the curved east end of the Circus Maximus. The triple arch was explicitly dedicated to Titus’ conquest of Judea and Jerusalem. It’s not very well known today because in the Middle Ages it fell victim to the Roman thirst for building materials, leaving only old epigraphic records, coins and drawings testifying to its existence. It was still standing with a relatively intact capital  when one of the anonymous authors of the Codex Einsidlensis (Einsiedeln manuscript no. 326) recorded the inscription in Inscriptiones Urbis Romae, an invaluable record of pagan and Christian epigraphy on monuments in the city of Rome that was written in the late 8th, early 9th century.

when one of the anonymous authors of the Codex Einsidlensis (Einsiedeln manuscript no. 326) recorded the inscription in Inscriptiones Urbis Romae, an invaluable record of pagan and Christian epigraphy on monuments in the city of Rome that was written in the late 8th, early 9th century.

A marked contrast with the inscription on the extant arch, the wording on the Circus Maximus arch’s inscription leaves no doubt that it was a genuine triumphal arch:

Senatus populusque Romanus imp(eratori) Tito Ceasari divi Vespasiani f(ilio) Vespasiani Augusto pontif(ici) max(imo), trib(unicia) pot(estate) x, imp(eratori) XVII, [c]o(n)s(uli) VIII, p(atri) p(atriae), principi suo, quod praeceptis patri(is) consiliisq(ue) et auspiciis gentem Iudaeorum domuit et urbem Hierusolymam, omnibus ante se ducibus regibus gentibus aut frustra petitam aut omnino intem(p)tatam, delevit.

The Senate and People of Rome [dedicate this arch] to the Emperor Titus [snip many titles], because by his father’s counsel and good auspices, he conquered the people of Judaea and destroyed the city of Jerusalem, which all of the generals, kings, and peoples before him had either failed to do or even to attempt.

In the 12th century the central arch was used as part of the Mariana aqueduct that Pope Calixtus II built to convey fresh water to the city in 1122. A few years later the powerful Frangipani family had control of the Circus Maximus. They built a mill powered by the Mariana and a tower, the Torre della Moletta, was integrated into the Frangipani’s defensive fortifications extending up the Palatine. Modest homes and squatters’ huts grew up all over what had once been a triumphal arch. The grounds of the Circus Maximus were converted to agricultural use, irrigated by the Mariana.

After the Unification of Italy in 1870, construction of the huge retaining walls along the banks of the Tiber and the Lungotevere boulevards cut off the Mariana or drove it underground into culverts. Most of the medieval construction around the Arch of Titus was demolished in the 1930s and 1940s, leaving only the tower, where Saint Francis of Assisi reputedly stayed on his last trip to Rome in 1223 as guest of the Graziano Frangipani’s widow and Franciscan lay sister Jacopa, still standing. Excavations at the time revealed medieval canals and walls made of ancient marbles pilfered from the arch.

Now archaeologists excavating the eastern hemicycle of the Circus Maximus have found large blocks of Carrara marble (marmor lunensis) that were part of the attic, entablature and columns of the Arch.

Now archaeologists excavating the eastern hemicycle of the Circus Maximus have found large blocks of Carrara marble (marmor lunensis) that were part of the attic, entablature and columns of the Arch.

Archaeologists found more than 300 marble fragments of the monument, some of them the size of a small car.

They discovered the bases of the four giant columns that formed the front of the arch, as well as the plinths on which they rested and traces of the original travertine pavement.

From the remains experts were able to calculate the arch’s original dimensions. It was 17 meters (56 feet) wide, 15 meters (49 feet) deep with columns 10 meters (33 feet) high. The full height including the attic has yet to be determined. In antiquity there was the monumental bronze sculpture of a quadriga on top of the arch which would have added significant vertical heft.

Excavation is difficult because the remains were found about 10 feet below ground level, which is on the wrong side of the water table. Further digging is going to require blocking off the water in the area, a particular challenge considering a river literally ran through the arch and its ruins for hundreds of years.

Archaeologists want to reconstruct as much of the arch as possible using the technique of anastylosis which attempts to put the ancient pieces back together as accurately as possible with only the modern materials necessary for structural stability. In order to do that, they’ll have to find a solution to the water seepage problem and a million euros, two daunting prospects. Since that’s sure to take time, the foundations will be reburied shortly for their own protection. Meanwhile, archaeologists are working on a virtual model of the triumphal Arch of Titus.

Here’s a puny slideshow of the site. The only really good views of the waterlogged excavation I could find are in this unembeddable ( :angry: ) Italian TV news story.