When the heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian Empire was found dead in a hunting lodge alongside the dead body of his 17-year-old mistress, it set off a chain reaction of confusion and cover-up that still continues to make the truth of what happened that tragic day elusive. The bodies of Crown Prince Rudolf of Austria and Baroness Mary Vetsera were discovered in the imperial lodge of Mayerling on the morning of January 30th, 1889, by the prince’s valet Loschek and his hunting companion Count Joseph Hoyos. Vetsera’s cold body was laid out on the bed; the prince’s was either sitting on a chair or lying down by her side.

When the heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian Empire was found dead in a hunting lodge alongside the dead body of his 17-year-old mistress, it set off a chain reaction of confusion and cover-up that still continues to make the truth of what happened that tragic day elusive. The bodies of Crown Prince Rudolf of Austria and Baroness Mary Vetsera were discovered in the imperial lodge of Mayerling on the morning of January 30th, 1889, by the prince’s valet Loschek and his hunting companion Count Joseph Hoyos. Vetsera’s cold body was laid out on the bed; the prince’s was either sitting on a chair or lying down by her side.

Loschek thought the prince had died from strychnine poisoning because he’d bled from the mouth, a misconception that would engender a lost-lasting rumor that Mary had poisoned Rudolf and then killed herself. That was story number one. There would be many, many more. And little wonder, since the immediate reaction of the imperial administration was to have the lodge sealed, Mary’s body hastily removed and buried in secret at the Cistercian monastery in nearby Heiligenkreuz. The public announcement from the Emperor stated that Rudolf had died from a heart aneurism. That was story number two. Mary was not mentioned.

Loschek thought the prince had died from strychnine poisoning because he’d bled from the mouth, a misconception that would engender a lost-lasting rumor that Mary had poisoned Rudolf and then killed herself. That was story number one. There would be many, many more. And little wonder, since the immediate reaction of the imperial administration was to have the lodge sealed, Mary’s body hastily removed and buried in secret at the Cistercian monastery in nearby Heiligenkreuz. The public announcement from the Emperor stated that Rudolf had died from a heart aneurism. That was story number two. Mary was not mentioned.

Rudolf’s body wasn’t examined by a doctor until that afternoon, and his determination that the Crown Prince had died from a gunshot wound to the temple, not poison, only made it to Franz Josef the next morning. With the press swarming and word getting out that there had been a mistress involved, the imperial PR machine churned up another announcement. Rudolf had killed Mary and then himself in a suicide pact. That was story three. Since it was rumored that the Emperor and Prince had had a huge fight in which the father demanded his son break up with his nouveau-riche teenage mistress (a rumor actively spread by German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck), the star-crossed lovers choosing death rather than lose each other seemed plausible. The police closed the investigation, such as it was, right quick.

Rudolf’s body wasn’t examined by a doctor until that afternoon, and his determination that the Crown Prince had died from a gunshot wound to the temple, not poison, only made it to Franz Josef the next morning. With the press swarming and word getting out that there had been a mistress involved, the imperial PR machine churned up another announcement. Rudolf had killed Mary and then himself in a suicide pact. That was story three. Since it was rumored that the Emperor and Prince had had a huge fight in which the father demanded his son break up with his nouveau-riche teenage mistress (a rumor actively spread by German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck), the star-crossed lovers choosing death rather than lose each other seemed plausible. The police closed the investigation, such as it was, right quick.

The Emperor secured a dispensation from the Pope so that his unshriven murderer/suicide son could be buried in the Imperial Crypt of Vienna’s Church of the Capuchins. In August of 1890, Franz Josef had the lodge rebuilt into a Carmelite convent, with the altar right over the spot where Rudolf and Mary were found dead. With the bodies moved and quickly buried, witnesses limited and/or compromised and the scene of the crime destroyed, there were few facts to support or contradict the official story, a lack of hard evidence which only increased suspicion and gossip about what really happened.

The Emperor secured a dispensation from the Pope so that his unshriven murderer/suicide son could be buried in the Imperial Crypt of Vienna’s Church of the Capuchins. In August of 1890, Franz Josef had the lodge rebuilt into a Carmelite convent, with the altar right over the spot where Rudolf and Mary were found dead. With the bodies moved and quickly buried, witnesses limited and/or compromised and the scene of the crime destroyed, there were few facts to support or contradict the official story, a lack of hard evidence which only increased suspicion and gossip about what really happened.

We can’t know how history would have unfolded if he’d survived, but Rudolf’s death had a tremendous impact on his family and on European politics. He was the only son of Emperor Franz Josef I of Austria and Empress Sisi. His death splintered his parents’ already troubled union and injected instability into the Hapsburg line of succession. Franz Josef’s younger brother Karl Ludwig became the heir to the imperial throne, and, after his death in 1896, his son Archduke Franz Ferdinand was heir presumptive. When Franz Ferdinand insisted on marrying the woman he loved, Countess Sophie Chotek, even though she did not match the stringent genealogical requirements of marriage into the imperial line, Franz Josef only allowed it on condition that the marriage be morganatic, ie, that none of Franz Ferdinand’s titles pass to his wife or children. That’s how committed Franz Josef was to the ancien régime strictures of his crown, so much that he would rather destabilize the succession again at a critical and dangerous time than allow a non-royal womb to bear future emperors. When Archduke Franz  Ferdinand was assassinated in Sarajevo on June 28th, 1914, igniting the powder keg that blew up into World War I and broke up the Austro-Hungarian Empire for good, the succession passed to Karl Ludwig’s second son Otto’s son Karl. He would reign as Charles I from 1916 until the end of the war in 1918.

Ferdinand was assassinated in Sarajevo on June 28th, 1914, igniting the powder keg that blew up into World War I and broke up the Austro-Hungarian Empire for good, the succession passed to Karl Ludwig’s second son Otto’s son Karl. He would reign as Charles I from 1916 until the end of the war in 1918.

Rudolf was politically liberal, unlike his archconservative father Emperor Franz Josef, and was more willing to grant political rights to the plethora of ethnic groups in Austria-Hungary. Bismarck was apparently quite happy that he wouldn’t have to deal with a Rudolfian Austro-Hungarian empire, but people hoping for a less autocratic monarchy were crushed. Given the central importance the question of ethnic self-determination would have in the post-war carving up of the empire and in the collapse of the Hapsburg dynasty, an Emperor Rudolf could have completely altered the map of Europe as we know it.

Little wonder, then, that double murder in the service of shadowy political interests was a popular theory, especially as Europe’s fragile power balance imploded into war. One of Rudolf’s aunt’s was sure they’d both been murdered by French agents because Rudolf refused to participate in a French plot to overthrow his father and install him on the throne because the liberal prince would be more amenable to an alliance with France rather than conservative Germany.

After World War II, the Red Army opened Mary Vetsera’s grave and monks claimed to have seen a tiny skeleton inside of the coffin when they closed it. That led to the theory that Mary might have died from an attempted abortion. When a Dr. Holler examined her remains in 1959, he found no bullet hole in her skull. The bones were in pieces from the Soviet interference, though, so his finding wasn’t conclusive. Holler asked for the Papal records of the event and apparently they noted that only one bullet was recovered from the scene, bolstering his failed abortion idea.

After World War II, the Red Army opened Mary Vetsera’s grave and monks claimed to have seen a tiny skeleton inside of the coffin when they closed it. That led to the theory that Mary might have died from an attempted abortion. When a Dr. Holler examined her remains in 1959, he found no bullet hole in her skull. The bones were in pieces from the Soviet interference, though, so his finding wasn’t conclusive. Holler asked for the Papal records of the event and apparently they noted that only one bullet was recovered from the scene, bolstering his failed abortion idea.

When Mayerling conspiracy theorist and furniture maker Helmut Flatzelsteiner secretly exhumed poor Mary’s remains in 1991 to perform his own autopsy, he insisted that it wasn’t even her body, but rather that of a relative who had died a century earlier. When he was caught trying to sell the remains in 1993, police confiscated Mary Vetsera’s bones and had an actual forensic specialist examine them for the first time. He confirmed that they were about 100 years old and belonged to a young woman who had died around age 20. No bullet hole was found in what was left of her skull, but because the skull was so fragmented that didn’t mean much. The cause of death remained unknown.

Now thanks to a remarkable find in a bank vault, we finally have some direct evidence of what happened. A brown leather-bound folder of documents discovered in the vaults of the private Schoeller Bank includes three signed and sealed suicide notes by Mary Vetsera to her mother Hélène, her sister Hannah and her brother Franz. The folder was found during an audit by the bank’s archivist, Sylvia Linc. It was deposited in a safe by persons unknown in 1926 and contains a number of Vetsera documents including her baptismal certificate and a copy of her death certificate and a long letter to her best friend Hermine Tobis.

Now thanks to a remarkable find in a bank vault, we finally have some direct evidence of what happened. A brown leather-bound folder of documents discovered in the vaults of the private Schoeller Bank includes three signed and sealed suicide notes by Mary Vetsera to her mother Hélène, her sister Hannah and her brother Franz. The folder was found during an audit by the bank’s archivist, Sylvia Linc. It was deposited in a safe by persons unknown in 1926 and contains a number of Vetsera documents including her baptismal certificate and a copy of her death certificate and a long letter to her best friend Hermine Tobis.

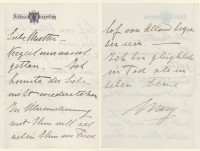

The farewell letters were written in Mary’s hand from Mayerling and still in the original envelope bearing the seal of Crown Prince Rudolf. A translation of her final note to her mother:

Dear Mother —

Forgive me what I have done. — I could not withstand love. In accordance with his wishes I want to be buried beside him in Alland cemetery. — I am happier in death than I was in life. Yours

Mary

Hélène wrote about the suicide notes in a 148-page memorandum to ensure that everything she knew about the events would survive the cover-up. After the bodies were found, Hélène had been told on by Count Eduard Taaffe, a close advisor of the Emperor’s, that her daughter had poisoned the unsuspecting Prince and then herself. Taaffe pressed her to put the blame for the tragedy on Mary’s shoulders with this poison story, claiming Mary had been seen at a lecture about poisons. He then suggested she leave Vienna but not go to Mayerling where, had she attended to her daughter’s body as she wanted, Hélène would surely have seen the hole in her head. Hélène thought his advice kind and well-intentioned, so her brothers went to Mayerling to see to the secret burial. Only upon their return did Hélène discover the truth, that it was Rudolf who had killed her daughter, not the other way around.

Hélène wrote about the suicide notes in a 148-page memorandum to ensure that everything she knew about the events would survive the cover-up. After the bodies were found, Hélène had been told on by Count Eduard Taaffe, a close advisor of the Emperor’s, that her daughter had poisoned the unsuspecting Prince and then herself. Taaffe pressed her to put the blame for the tragedy on Mary’s shoulders with this poison story, claiming Mary had been seen at a lecture about poisons. He then suggested she leave Vienna but not go to Mayerling where, had she attended to her daughter’s body as she wanted, Hélène would surely have seen the hole in her head. Hélène thought his advice kind and well-intentioned, so her brothers went to Mayerling to see to the secret burial. Only upon their return did Hélène discover the truth, that it was Rudolf who had killed her daughter, not the other way around.

Several copies of the memorandum are known to have survived, but this is the first time documents mentioned in it have been found. The only other primary document relating to the Mayerling Incident known to have survived is Rudolf’s farewell letter to his wife, now in the collection of the Austrian National Library, in which he says his death would be better for everyone, but does not come right out and say he’s going to kill himself and his girl. The discovery of Mary Vetsera’s original suicide notes, therefore, is of great historical import in a case that was muddied and obscured from the very beginning.

The bank has given the documents to the Austrian National Library (ONB) on permanent loan where they will be conserved, catalogued and digitized. As of this month, the Vetsera documents will be made available for scholarly research. Next year some of them will go on public display for the first time in an exhibition at the library dedicated to the 100th anniversary of Emperor Franz Josef’s death.