Microscopes had been used by scientists before Anton van Leeuwenhoek perfected the lenses that allowed him to see the unseen in the late 17th century, but it was Leeuwenhoek who first viewed animalcules in a drop of water. For almost two centuries after him, the microscope remained the province of the scientist and the wealthy amateur. Advancements in technology and mass-production in the 19th century made the microscope more widely accessible. If you didn’t have your own, a traveling showman would let you enjoy his, for a modest fee, of course. That meant regular people could peer into a drop of water and find it teaming with creatures.

Microscopes had been used by scientists before Anton van Leeuwenhoek perfected the lenses that allowed him to see the unseen in the late 17th century, but it was Leeuwenhoek who first viewed animalcules in a drop of water. For almost two centuries after him, the microscope remained the province of the scientist and the wealthy amateur. Advancements in technology and mass-production in the 19th century made the microscope more widely accessible. If you didn’t have your own, a traveling showman would let you enjoy his, for a modest fee, of course. That meant regular people could peer into a drop of water and find it teaming with creatures.

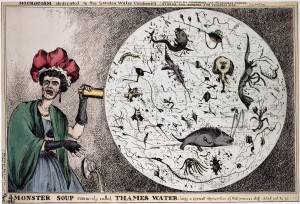

This was disconcerting at first. In 1828, after the Commission on the London Water Supply reported that the Thames, supplier of drinking water for the capital, was contaminated by raw sewage, William Heath illustrated people’s reaction at their impure water with a caricature in which a woman views the “Monster Soup commonly called Thames water” through a microscope with horror. In the United States, even as late as 1846 the thriving social life in a drop of water from New York’s recently built Croton Reservoir alarmed the erudite gentlemen of Scientific American.

Yet, just a few years after that, with microscopes getting stronger, cheaper and more portable every day, the “creatures of malignant and voracious propensities” in the Croton reservoir that had so disturbed Scientific American were seen as a source of viewing pleasure, live entertainment for anyone with the technology to enjoy them. Amateur naturalist Agnes Catlow, author of books on botany, entomology, zoology and shells, wrote Drops of Water: Their Marvelous and Beautiful Inhabitants Displayed by the Microscope in 1851 specifically for the beginner.

Yet, just a few years after that, with microscopes getting stronger, cheaper and more portable every day, the “creatures of malignant and voracious propensities” in the Croton reservoir that had so disturbed Scientific American were seen as a source of viewing pleasure, live entertainment for anyone with the technology to enjoy them. Amateur naturalist Agnes Catlow, author of books on botany, entomology, zoology and shells, wrote Drops of Water: Their Marvelous and Beautiful Inhabitants Displayed by the Microscope in 1851 specifically for the beginner.

General interest and literary magazines stepped on the microscopy bandwagon as well, for instance Charles Dickens’ magazine Household Worlds. Dickens published his own serialized works in the magazine as well as the work of other writers like his protegé Wilkie Collins. He wanted this to be a family periodical — uplifting, wholesome, socially responsible – and exerted total control over its content. In keeping with this ethos, the Microscopic Preparations article published in the fall of 1857 showed readers how, from the comfort of their own homes, they could enjoy the fascinating world of microorganisms while unconsciously improving their understanding of nature.

The popular English philosopher and polymath Herbert Spencer went further, insisting that an active exploration of the natural world was necessary not only for the development of reason and the intellect, but for the development of aesthetic understanding as well. In “What Knowledge Is of Most Worth,” first published in the Westminster Review then with three other related essays in an 1860 book Education: Intellectual, Moral and Physical, Spencer wrote:

The popular English philosopher and polymath Herbert Spencer went further, insisting that an active exploration of the natural world was necessary not only for the development of reason and the intellect, but for the development of aesthetic understanding as well. In “What Knowledge Is of Most Worth,” first published in the Westminster Review then with three other related essays in an 1860 book Education: Intellectual, Moral and Physical, Spencer wrote:

The truth is, that those who have never entered upon scientific pursuits know not a tithe of the poetry by which they are surrounded. Whoever has not in youth collected plants and insects, knows not half the halo of interest which lanes and hedge-rows can assume. Whoever has not sought for fossils, has little idea of the poetical associations that surround the places where imbedded treasures were found. Whoever at the seaside has not had a microscope and aquarium, has yet to learn what the highest pleasures of the seaside are.

Those who seek truth and understanding from the study of history, art and literature while ignoring science, Spencer believed, are bogged down by surperficialities and minutiae, depriving themselves of the greatest form of poetry: “that grand epic written by the finger of God upon the strata of the Earth.”

And thus seaside microscopy became a popular hobby in the second half of the 19th century. In less than 15 years, the tiny creatures in water went from malignant to beautiful to edifying to the greatest thing a beach vacation has to offer, and that was just in non-fiction. The January 1858 issue of The Atlantic Monthly (the now-venerable magazine’s third issue ever), featured a story by Irish author Fitz James O’Brien called The Diamond Lens in which a microscopist speaks to the spirit of Leeuwenhoek through a medium and gets instructions from the master on how to craft the perfect microscope: by using a 140-carat diamond lens bombarded with electro-magnetic currents. With this ultimate microscope, our hero sees past the “grosser particles” of the animalcules into a radiant paradisiacal realm where he finds the most beautiful wee blond lady ever. He names her Animula and of course falls madly in love with her.

I find it fascinating that microorganisms transformed in the public imagination from voracious beasts to otherworldly naiads just as people were beginning to figure out that there actually IS stuff in the water that can kill you. For example, pioneering epidemiologist John Snow had some understanding that something in water caused cholera. He didn’t know what exactly, but he thought water contaminated with the feces of cholera victims transported material to the digestive tracks of healthy people, material that would then reproduce itself avidly infecting its hosts with cholera. He published his first paper on the subject in 1849 and nobody believed him. They didn’t believe him five years later when he helped end an 1854 cholera outbreak by having the handle of the Broad Street water pump located in the thick of the infection zone removed. Miasmas (putrid fogs emanating from decomposing tissue) were still widely believed to be the transmitters of disease.

I find it fascinating that microorganisms transformed in the public imagination from voracious beasts to otherworldly naiads just as people were beginning to figure out that there actually IS stuff in the water that can kill you. For example, pioneering epidemiologist John Snow had some understanding that something in water caused cholera. He didn’t know what exactly, but he thought water contaminated with the feces of cholera victims transported material to the digestive tracks of healthy people, material that would then reproduce itself avidly infecting its hosts with cholera. He published his first paper on the subject in 1849 and nobody believed him. They didn’t believe him five years later when he helped end an 1854 cholera outbreak by having the handle of the Broad Street water pump located in the thick of the infection zone removed. Miasmas (putrid fogs emanating from decomposing tissue) were still widely believed to be the transmitters of disease.

The official report (pdf) of the government committee tasked with studying the cholera epidemic of 1854 went out of their way to reject Snow’s unappealing idea, twisting the facts he had established to fit the miasmic theory.

The official report (pdf) of the government committee tasked with studying the cholera epidemic of 1854 went out of their way to reject Snow’s unappealing idea, twisting the facts he had established to fit the miasmic theory.

The water was undeniably impure with organic contamination ; and we have already argued that, if, at the times of epidemic invasion there be operating in the air some influence which converts putrefiable impurities into a specific poison, the water of the locality, in proportion as it contains such impurities, would probably be liable to similar poisonous conversion. Thus, if the Broad Street pump did actually become a source of disease to persons dwelling at a distance, we believe that this may have depended on other organic impurities than those exclusively referred to, and may have arisen, not in its containing choleraic excrements, but simply in the fact of its impure waters having participated in the atmospheric infection of the district.

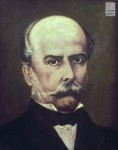

In fact, the very year cholera hit Broad Street, anatomist Filippo Pacini at the University of Florence isolated the cholera bacillus from the intestinal muscosa of one of its victims. He published his discovery that year, but it got no traction in the international scientific community, nor did his several subsequent studies connecting to the pathogen to the pathology. Thirty years later, Robert Koch made the same discovery independently and, even though the miasma theory was still predominant for a few years, eventually Koch’s ideas were accepted. Pacini finally got wide credit for being the first when his last name was added to the bacillus — Vibrio cholerae Pacini — in 1965.

In fact, the very year cholera hit Broad Street, anatomist Filippo Pacini at the University of Florence isolated the cholera bacillus from the intestinal muscosa of one of its victims. He published his discovery that year, but it got no traction in the international scientific community, nor did his several subsequent studies connecting to the pathogen to the pathology. Thirty years later, Robert Koch made the same discovery independently and, even though the miasma theory was still predominant for a few years, eventually Koch’s ideas were accepted. Pacini finally got wide credit for being the first when his last name was added to the bacillus — Vibrio cholerae Pacini — in 1965.