Archaeologists from Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) have unearthed part of a large rack of human skulls in the Templo Mayor complex in Mexico City. The Aztecs would pierce the heads of the sacrificed, string them together on wooden stakes and mount them on a vertical posts. This structure, called a tzompantli, would be erected for all to see as a highly effective symbol of ruthless power. A five-skull tzompantli was discovered underneath a sacrificial stone and a mound of skulls and jawbones at the Templo Mayor in 2012, but this latest discovery is on a whole other scale. Archaeologists believe it is the major tzompantli of the Aztec city of Tenochtitlan described in Spanish accounts of the city before its destruction in 1521.

Archaeologists from Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) have unearthed part of a large rack of human skulls in the Templo Mayor complex in Mexico City. The Aztecs would pierce the heads of the sacrificed, string them together on wooden stakes and mount them on a vertical posts. This structure, called a tzompantli, would be erected for all to see as a highly effective symbol of ruthless power. A five-skull tzompantli was discovered underneath a sacrificial stone and a mound of skulls and jawbones at the Templo Mayor in 2012, but this latest discovery is on a whole other scale. Archaeologists believe it is the major tzompantli of the Aztec city of Tenochtitlan described in Spanish accounts of the city before its destruction in 1521.

The team was digging in a well under the floor of a colonial-era home on the western side of the temple complex. Six feet under floor level, they discovered a wall of volcanic rock coated with stucco with a flagstone floor. The rectangular platform, estimated to be more than 34 meters (111.5 feet) long and 12 meters (40 feet) wide, has at its center a circular structure made from skulls cemented together using a lime, sand and volcanic gravel mortar. Many of the skulls have a hole 25 to 30 centimeters (10-12 inches) in diameter piercing the parietal bones. They are all facing inwards at the open space inside the circle. Adult male skulls predominate, but there are skulls from adult women, youths and children as well. So far archaeologists have counted 35 skulls, but expect to see that number increase exponentially as they dig further down under the stucco and stone slabs.

The team was digging in a well under the floor of a colonial-era home on the western side of the temple complex. Six feet under floor level, they discovered a wall of volcanic rock coated with stucco with a flagstone floor. The rectangular platform, estimated to be more than 34 meters (111.5 feet) long and 12 meters (40 feet) wide, has at its center a circular structure made from skulls cemented together using a lime, sand and volcanic gravel mortar. Many of the skulls have a hole 25 to 30 centimeters (10-12 inches) in diameter piercing the parietal bones. They are all facing inwards at the open space inside the circle. Adult male skulls predominate, but there are skulls from adult women, youths and children as well. So far archaeologists have counted 35 skulls, but expect to see that number increase exponentially as they dig further down under the stucco and stone slabs.

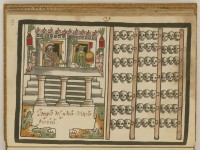

Preliminary dating places this structure in Stage VI of the construction of the Templo Mayor (between 1486 and 1502), during the reign of Aztec warrior king Ahuízotl. He was succeeded on the throne of Tenochitlan by his nephew Moctezuma II who would meet his end fighting Conquistador Hernán Cortés. Cortés himself described the great tzompantli of Tenochtitlan, as did early ethnographers Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún and Dominican friar Diego Durán. They wrote of tzompantli with low, elongated bases supporting the vertical posts with horizontal racks of skulls. There is also at least one account of skulls mortared together; this is the first time a tzompantli has been discovered matching that description.

Preliminary dating places this structure in Stage VI of the construction of the Templo Mayor (between 1486 and 1502), during the reign of Aztec warrior king Ahuízotl. He was succeeded on the throne of Tenochitlan by his nephew Moctezuma II who would meet his end fighting Conquistador Hernán Cortés. Cortés himself described the great tzompantli of Tenochtitlan, as did early ethnographers Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún and Dominican friar Diego Durán. They wrote of tzompantli with low, elongated bases supporting the vertical posts with horizontal racks of skulls. There is also at least one account of skulls mortared together; this is the first time a tzompantli has been discovered matching that description.

University of Florida archaeologist Susan Gillespie, who was not involved in the project, wrote that “I do not personally know of other instances of literal skulls becoming architectural material to be mortared together to make a structure.” […]

“They’ve been looking for the big one for some time, and this one does seem much bigger than the already excavated one,” Gillespie wrote. “This find both confirms long-held suspicions about the sacrificial landscape of the ceremonial precinct, that there must have been a much bigger tzompantli to curate the many heads of sacrificial victims” as a kind of public record or accounting of sacrifices.

The second stage of excavations will begin in November. Meanwhile, the skulls will be examined in the laboratory. They’ll test the DNA if they can recover any and will test stable isotopes in the bones and teeth to determine the geographic origin of the sacrificed.