A manuscript score by Claude Debussy has reemerged more than 90 years after it was last seen. Composed by Debussy when he was just 19 years old and struggling to make ends meet as a voice teacher, the piece is a score, piano and voice, for the play Hymnis by poet Théodore de Banville who along with Paul Verlaine was the poet who most influenced the young composer.

A manuscript score by Claude Debussy has reemerged more than 90 years after it was last seen. Composed by Debussy when he was just 19 years old and struggling to make ends meet as a voice teacher, the piece is a score, piano and voice, for the play Hymnis by poet Théodore de Banville who along with Paul Verlaine was the poet who most influenced the young composer.

The score was never published and the manuscript was last documented in 1926 when it was sold at auction in Paris. It never made it into any catalogues of the composer’s works and basically disappeared until November of 1917 when a client asked the manuscripts experts at Christie’s Paris to take a look at a manuscript of his and tell him what it was.

This manuscript, which hasn’t been seen or played in public in almost a century since it last appeared at auction in 1926, is one of three known scores for Hymnis that Debussy worked on. Of the others, one contains his strophes for the opening scene, the second for the beginning of scene seven. Both, however, feature different music for the same parts of the play.

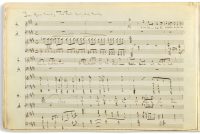

Offered in Paris on 29 May, the manuscript contains a further 15 pages of previously unseen music by Debussy. “Everyone I’ve talked to, every musician, is excited, because of course we get to look at this music maybe for the first time in 100 years,” says the composer and pianist Jeff Cohen, who plays the score in our film. “I found that even touching the paper itself is quite moving. Seeing Debussy’s handwriting, it’s as if he is standing there next to you — it’s so personal.”

It was personal in more ways than just the handwriting. Debussy’s first published work was Nuit d’étoiles (1882), set to the poem by the same name by Banville. He wrote the Hymnis score around that time, in 1881-1882, and like his other pieces inspired by the Symbolist poet, it is dedicated to his lover, muse and vocal student Marie Vasnier. She was a cultured woman 14 years older than him who taught him a great deal about the arts, including the amatory ones. She was also married. To top it off, in 1882 they were separated when Debussy traveled through Europe with his patroness Nadejda von Meck. The threesome at the heart of the story of Hymnis may have had particular resonance for him given the complications of his relationship to a married woman.

It was personal in more ways than just the handwriting. Debussy’s first published work was Nuit d’étoiles (1882), set to the poem by the same name by Banville. He wrote the Hymnis score around that time, in 1881-1882, and like his other pieces inspired by the Symbolist poet, it is dedicated to his lover, muse and vocal student Marie Vasnier. She was a cultured woman 14 years older than him who taught him a great deal about the arts, including the amatory ones. She was also married. To top it off, in 1882 they were separated when Debussy traveled through Europe with his patroness Nadejda von Meck. The threesome at the heart of the story of Hymnis may have had particular resonance for him given the complications of his relationship to a married woman.

Several specialists consider that the melodies written for Marie Vasnier are as many love notes that he addresses to him, Hymnis, perhaps more than the others. Thus Eileen Souffrin-Le Breton, later taken up by François Lesure, wonders: “We can ask ourselves about Hymnis if Debussy did not have intimate reasons to love the piece … How (…) do not to see an analogy between the situation of the three characters of Hymnis and Debussy himself vis-à-vis the Vasnier household? (…) When Hymnis sings:

“He sleeps again, one hand on the lyre ! / (…) / Divine Charmer, while you sleep / around you flutter the bees: / The sweet poet is the envoy of the Gods “.

How not to imagine Mrs. Vasnier in the traits of a Hymnis (first) protective (and) maternal:

“To be proud of your genius / To surround yourself as a child / To be encouraged and defended “.

(or) burning (with) passion:

“In the ardor that tears me / The heart full of you, / I offer you, O my king, / My fury and my delirium”

(And the composer in the traits of) Anacreon who proclaims:

“Hymnis! Oh half of myself / Dear Hymnis! I love you”

(To finish with the duet):

“Ah, we are blessed …”.

The manuscript goes under the hammer at Christie’s Paris at the end of the month. The pre-sale estimate is 120,000 – 180,000 euros ($141,856 – $212,785). Composer and pianist Jeff Cohen accompanies soprano Pauline Texier perform a short preview of the score in the video at the top of this page.