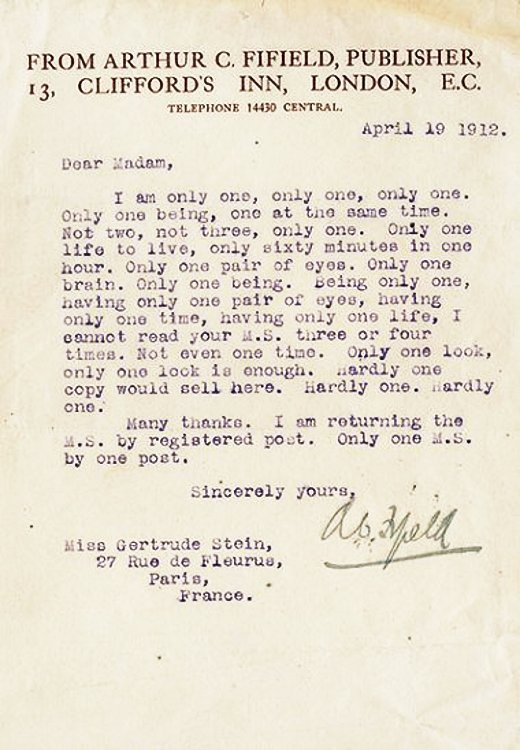

Courtesy of Letters of Note, check out this brilliant rejection letter sent by editor Arthur C. Fifield to Gertrude Stein of “a rose is a rose is a rose” fame in 1912:

Given the 1912 date, I suspect Mr. Fifield was so spiritedly rejecting Stein’s second book, Portrait of Mabel Dodge at Villa Curonia.* Her first book was 1909’s Three Lives, a trilogy of novellas. It had been fairly successful and Stein was already well-known for her and her brother Leo’s impressive art collection of Matisses, Picassos, Gauguins, Braques, Cézannes, Renoirs, Toulouse-Lautrecs, and her Saturday evening salons which many of her favorite artists attended religiously along with the rest of bohemian turn of the century Paris.

Her fame and earlier publishing success weren’t enough to make Stein’s repetitious, abstract, stream of consciousness style in Portrait of Mabel Dodge at Villa Curonia appeal to publishers. Everyone she sent the manuscript to rejected it. Ultimately it made it into print thanks only to Mabel Dodge herself who privately published 300 copies, all of which are now hugely valuable collector’s pieces.

Mabel Dodge Luhan was an heiress and art patron who between 1905 and 1912 held court at Villa Curonia, a Renaissance estate outside of Florence that had been built by the Medici family in the 15th century. She met Gertrude Stein in 1911 and they became friends. She loved Stein’s writing, appreciating the music in the cadences and rhythms that seem to have failed to impress poor Mr. Fifield.

Mabel encouraged her writing and invited her to stay at Villa Curonia many times. “Please come down here soon,” Mabel wrote Gertrude in 1913. “The house is full of pianists, painters, pederasts, prostitutes, and peasants. Great material.”

She was tickled pink when Gertrude composed a word portrait of her and her beautiful home during one of her many stays at Villa Curonia, so when publishers rejected the manuscript, Mabel Dodge stepped up to the plate. She distributed those 300 copies at the 1913 New York Armory Show, aka the International Exhibition of Modern Art — the first exhibit of modernist art in the United States, which of course scandalized art critics and public — and they would make her famous.

She was tickled pink when Gertrude composed a word portrait of her and her beautiful home during one of her many stays at Villa Curonia, so when publishers rejected the manuscript, Mabel Dodge stepped up to the plate. She distributed those 300 copies at the 1913 New York Armory Show, aka the International Exhibition of Modern Art — the first exhibit of modernist art in the United States, which of course scandalized art critics and public — and they would make her famous.

* EDIT: I was wrong. I double checked the dates and Stein didn’t write Portrait until October of 1912. The manuscript Fifield rejected must have been The Making of Americans, a novel Stein worked on in bursts between 1903 and 1911. It would remain unpublished until a small French press published a 500 copy run in 1925. Mabel loved it, though. She thought it was revolutionary and brilliant. In a 1911 letter to Stein, Dodge wrote about The Making of Americans:

To me it is one of the most remarkable things I have ever read. There are things hammered out of consciousness into black & white that have never been expressed before — so far as I know. States of being put into words, the “noumenon” captured — as few have done it. To name a thing is practically to create it & this is what your work is — real creation… your palette is such a simple one — the primary colors in word painting & you express every shade known & unknown with them. It is as new & strange & big as the post-impressionists in their way &, I am perfectly convinced, it is the forerunner of a whole epoch of new form & expression …. I feel it will alter reality as we know it, & help us to get at Truth instead of away from it as “literature” so sadly often does.